Mahupuku, Hamuera Tamahau

Little is known of Tamahau’s childhood or education. It is likely that he was baptised by William Colenso or William Ronaldson of the Church Missionary Society. He may have been self-educated, but could have been a pupil at St Thomas’s College at Papawai between 1860 and 1864. In the mid 1860s Tamahau was known as a rather wild young man who had worked for a time on Huangarua station. He was handsome, mixed much with Europeans, and for some years worked as a cattle drover. His brother was an ardent supporter of the Maori King movement, and, at least in the 1860s, Tamahau followed his lead.

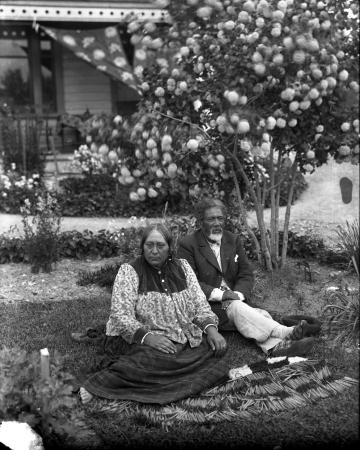

Tamahau had three wives; the marriages were concurrent. His first wife, variously known as Wairata, Harete, Areta or Alice, was said to be the very beautiful part-Maori daughter of Jack Pain, an old whaler. His third wife, known as Clara, may have been of Nga Puhi. But Raukura, Tamahau’s second wife, had the most influence on his future. Her first husband was Matini Te Ore, and through this connection Tamahau gained influence at Papawai and was brought into contact with Te Manihera Te Rangi-taka-i-waho, who later appointed him his heir in matters to do with the people.

Tamahau had three wives; the marriages were concurrent. His first wife, variously known as Wairata, Harete, Areta or Alice, was said to be the very beautiful part-Maori daughter of Jack Pain, an old whaler. His third wife, known as Clara, may have been of Nga Puhi. But Raukura, Tamahau’s second wife, had the most influence on his future. Her first husband was Matini Te Ore, and through this connection Tamahau gained influence at Papawai and was brought into contact with Te Manihera Te Rangi-taka-i-waho, who later appointed him his heir in matters to do with the people.

This appointment was one foundation of Tamahau’s leading position at the growing Maori centre at Papawai; the other was the Mahupuku wealth. As members of one of the two leading families of Ngati Hikawera, Tamahau and Hikawera controlled a large part of the Nga-waka-a-Kupe block and had interests in several more. They leased land profitably and Hikawera developed his own sheep station. He fought attempts by Ngatuere Tawhirimatea Tawhao and Te Manihera to sell Nga-waka-a-Kupe. In the Native Land Court in 1890, and again in 1892, the judges upheld Ngati Hikawera’s claim to the block against the claims of Ngatuere and Ngati Kahukura-awhitia. Tamahau was heir to his brother’s wealth as well as his prestige on Hikawera’s death in 1891.

Tamahau had also worked as an assessor and agent in the Native Land Court. While claims to the Wairarapa lakes were being heard in 1882 and 1883 he acted for Hoani Te Toru. In introducing lists of potential owners Tamahau was working against Piripi Te Maari-o-te-rangi and Te Manihera, who wanted the hearing dismissed. He and Paraone Pahoro managed to persuade Raniera Te Iho-o-te-rangi and Piripi Te Maari of the benefits of registering the lake owners, who included Tamahau and Hikawera.

Two months after Te Manihera’s death in 1885, Tamahau was taking his place at important meetings, but shared the leadership at Papawai with Te Manihera’s half-brother, Hoani Te Rangi-taka-i-waho. He continued to develop the centre: a large house with an iron roof and stained glass windows was erected for visitors (and later replaced by the house, Hikurangi). Wooden houses were built with the proceeds of sales of totara from Mahupuku properties. A team of Ngati Porou carvers worked at Papawai during the 1880s, preparing the carvings for the great house Hikawera had planned. Eventually Hikawera presented them to Tamahau who erected the house, Takitimu, at Kehemane (Tablelands) early in the 1890s. Te Kooti attended its opening and predicted, perplexingly, that the wind would blow through it.

Perhaps Tamahau’s affluence accounts for his enthusiastic acceptance of all things Pakeha, and his support of various governments’ paternalistic plans for the Maori people. In 1891 he told the Native Land Laws Commission that he did not want Maori committees to be given the power to deal with Maori lands because he did not want the existing Wairarapa boundaries upset. He joined in the parliaments of the Kotahitanga movement from 1893, but refused to sign the deeds which set out the movement’s aims; he was suspicious of a clause which vested control of Maori land in the Kotahitanga government. In any Kotahitanga bills he consistently opposed wording which demanded separate powers. Henare Tomoana once snarled that Tamahau had argued about the same phrase for 10 days on end. Although he had still not signed the deeds, in 1895 he began to suggest that the parliament sit at Papawai.

Piripi Te Maari died on 26 August 1895. Within five months Tamahau had reached an agreement with the government for the sale of the Wairarapa lakes, which Piripi had always resisted. Tamahau requested continued Maori access to the lakes for fishing, and trusted the government to select suitable lands as compensation. (Cheap land in the King Country was eventually selected.) As a sign that all hostilities between the former Maori owners and the new settlers were at an end, he gave a grand picnic at Pigeon Bush. The politicians Richard Seddon and James Carroll and the settlers were welcomed with Tamahau’s finest oratory. Seddon emphasised that the lakes had not been sold but presented to the government; the £2,000 handed over as part of the deal was intended to cover the litigation expenses of the former owners.

Tamahau, principally responsible for ending the deadlock over the lakes, was afterwards regarded as a personal friend of Seddon. In 1897 Seddon, Lord Ranfurly (the governor) and other European notables accepted his invitation to the opening of the Aotea–Te Waipounamu complex built at Papawai for the Kotahitanga parliament. This was a T-shaped, partly two-storeyed building, including a dormitory, a dining room and a meeting hall with a raised dais for speakers. On this occasion Tamahau offered to the government the superlative carved house, Takitimu. He renewed his offer in 1898.

Tamahau was host to two sessions of the Kotahitanga parliament at Papawai in 1897, in April and October. During the sessions it was decided to inquire into the results of Te Keepa Te Rangihiwinui’s petition to the Queen that the five million remaining acres of Maori land should be reserved absolutely for Maori. Tamahau led the group which subsequently approached Seddon in Wellington. Seddon told them that the Queen considered Maori welfare to be the colonial government’s responsibility, and he was giving the matter his consideration. He suggested for the first time the setting up of Maori land boards.

Another 1897 project of Tamahau’s was the publication of the Maori-language newspaper Te Puke ki Hikurangi, edited by Purakau Maika. At first very much a vehicle to report the activities of the Kotahitanga movement, it soon expanded to include religious articles, advice on domestic matters for women, reports of foreign and local non-Maori news, and correspondence on canoe traditions and genealogy. One series of articles, to which Apirana Ngata contributed, was on Maori depopulation, its causes and remedies. In the newspaper’s pages Tamahau advertised for knowledgeable people to come to his hui to record Maori tradition and genealogy. This campaign led to the setting up of the Tane-nui-a-rangi committee, responsible for the preservation of much traditional material. This work, and publication of the newspaper itself, continued after Tamahau’s death. Te Puke ki Hikurangi was a major formative and educative influence on contemporary Maori.

Following his 1897 initiative, in 1898 Seddon drafted a bill ‘to provide for the Settlement and Administration of Native Lands’. The bill created a furore among Maori, mainly because of its paternalistic aspects. Tamahau set up a grand meeting at Papawai in May and June 1898 to discuss it. The meeting revealed a deep rift between Kotahitanga members in their attitudes: many rejected the bill outright, but a group of pro-government chiefs including Tamahau drew up a series of amendments, ensuring a Maori majority on the proposed Maori land boards and making other changes for greater local Maori control of land and social affairs. Many important Kotahitanga members rejected these amendments, since they had been adopted in defiance of the rules and regulations of the Kotahitanga parliament. In September Tamahau petitioned the government to adopt the bill with the Papawai amendments, but other petitions demanded that it be scrapped. When an inquiry was held by the Native Affairs Committee Tamahau expressed his faith and trust in the government, stating that Maori had never been disadvantaged by parliamentary legislation and that their grievances sprang from ignorance and improvidence.

Although nominally a member of Te Kotahitanga, Tamahau did not share its aim of self-determination. He was a member of a committee working outside the legislature to support Seddon’s 1900 Maori Lands Administration Act (which had eventually been passed as a result of the 1898 bill) and Maori Councils Act. These acts seemed in the early years of their administration to meet at least some Maori aspirations to local self-government and Maori-controlled reform. Their potential benefits were enthusiastically discussed in Te Puke ki Hikurangi, and the surviving leaders of Te Kotahitanga, beginning with Tamahau, praised for having achieved this result.

From 1894 to 1904 Tamahau was said to have spent more than £40,000 on various projects. These included his financial support of the Wairarapa Mounted Rifle Volunteers, a Maori company. In 1901 he offered to raise and finance a Maori force to fight in the South African war. The offer was refused by the British government, which had decided to use only white troops in the war.

At hui at Papawai and Kehemane, Tamahau was host to thousands. A brass band he supported played at these functions and accompanied him on his visits into town. One of his last projects was to erect a palisade to enclose the marae at Papawai. Totara logs were collected and after his death were carved into representations of important ancestors and erected facing into the marae, according to his wish, to symbolise peace. (Traditionally, carved figures faced outwards to threaten enemies.)

Tamahau died at Papawai on 14 January 1904. He left no children but had adopted Aketu Piripi, who died at the age of 17. An Anglican service was conducted in Maori, and the body was taken for burial at Kehemane, followed by a large crowd. His mourners included Seddon and Carroll. By contemporary Europeans Tamahau was regarded as one of the most ‘progressive’ of Maori. To the large Maori community at Papawai he was father and leader.

After his death the glory of Papawai as the rendezvous of two governments – of the colony and of Te Kotahitanga – faded. No one replaced him, and few could afford to finance the huge gatherings of the past. Many felt that the Maori councils, whose setting up he had supported, would make such leaders redundant. Aotea–Te Waipounamu blew down in a storm in 1934, and a marble monument to Tamahau’s memory, unveiled at Papawai in 1911, was damaged by earthquake in 1942. The totara palisades gradually collapsed, and at Kehemane on 31 December 1911 Takitimu burned to the ground. As Te Kooti had predicted at its opening, now only the wind blew through the site.