The following articles were written by Gareth Winter, Wairarapa Archivist. Each article contributes to a body of work that highlights aspects of Wairarapa history. The series features on the Masterton District Library website.

Joseph Masters And Retimana Te Korou

Buried less than fifty metres apart in the Masterton Cemetery are the two main people involved in the purchase of the site of Masterton, which led to the establishment of the northern-most of the two Small Farms Association settlements in Wairarapa.

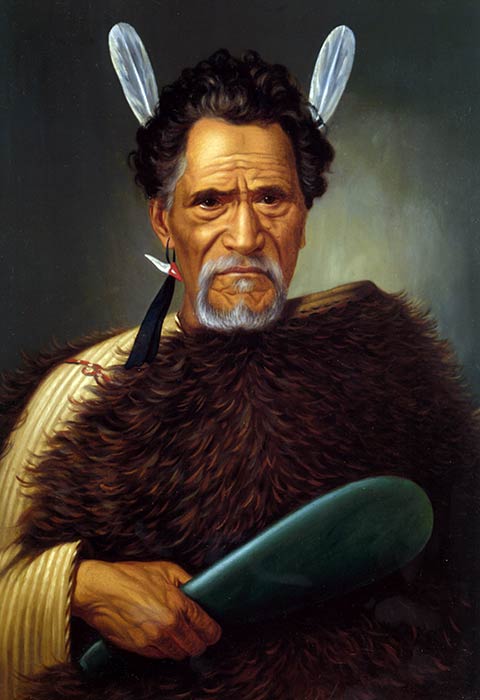

In the Pioneer Section lies Joseph Masters, prime instigator of the movement to establish the Small Farms Association, while nearby in the main part of the cemetery a simple grave marks the burial place of Retimana Te Korou, Rangitane chief.

Te Korou was born in the later years of the eighteenth century, son of Te Raku and Te Kai. His parents belonged to the Rangitane and Ngati Kahungunu peoples of Wairarapa.

Joseph Masters was born in 1802, in Derby, England, where his father was a leather breeches manufacturer. His father died when he was very young, and he was sent to work in a silk mill, threading the bobbins. Masters’ mother remarried and Joseph was sent off to live with his grandmother, but he was soon shifted on again. He ended up living with, and working for, his uncle in Rugby, where he served an apprenticeship as a cooper. Masters seems to have been driven by a strong desire to better himself, and once he had gained his trade he left his uncle, serving as a Grenadier Guard before working as a policeman and gaoler. In 1826 he married Sarah Bourton, and in 1832 Joseph Masters, his wife and his two daughters migrated to Tasmania, where Masters found work as a cooper serving the whaling industry.

About the same time that Masters was making his move, Te Korou was also on the move.

The Taranaki tribes who had made their way to the Wellington area with Te Rauparaha, had pushed their way eastwards, and a number of families were living in Wairarapa. At first the new arrivals lived alongside the Kahungunu and Rangitane people they found living here, but troubles eventually arose and a series of battles were fought between the two groups. Some of these battles went well for the locals, but there were bad setbacks too, with some battles lost and some warriors captured. Te Korou was among those caught. Te Wera of Ngati Mutunga was taking him to Wellington when Te Korou escaped by killing Te Wera. Realising it was no longer safe in Wairarapa, Te Korou, his wife Hine-whaka-aea, and their children joined other Wairarapa Maori at the east coast stronghold of Nukutaurua, on Mahia Peninsular, where they remained until 1841.

Joseph Masters was still looking for ways to improve himself, and deciding to leave Tasmania, headed for New Zealand. He landed first in the Bay of Islands, but quickly made his way south to Wellington. He started business as a ginger beer manufacturer, but by the mid 1840s had reverted to his old trade as a cooper in Lambton Quay.

Te Korou had also headed south at the same time, firstly as a member of a group of Wairarapa chiefs that had made peace with the Taranaki Maori still living in Wellington, then as a resident on his family’s ancestral lands. When the missionary William Colenso called in to Kaikokirikiri pa, on the banks of the Waipoua River above what was to become Masterton, a Maori teacher had already converted Te Korou to Christianity. Te Korou’s family was all baptised and they adopted new names. Te Korou chose Retimana (Richmond) as his new name, his wife became Hoana (Joan) and his surviving children Erihapeti (Elizabeth) and Karaitiana (Christian).

Te Korou was involved in encouraging pakeha settlement, offering some of his coastal land to the pastoralists Weld, Clifford and Vavasour, then later leasing Manaia station to Rhodes and Donald.

Joseph Masters was also looking at Te Korou’s land. He had been writing a series of letters to the Wellington Independent promoting the concept of small farm settlements. His plan was that groups of working men should pool together and buy blocks of land from the Government that they could subdivide among themselves. Each of the members would own a small town section and a 40-acre farm.

After a meeting in March 1853, a Small Farms Association was formed and Masters and C.R. Carter visited Governor Grey, convincing him of the merits of their scheme. He informed them that he was happy to support their scheme for settlement in Wairarapa as long as they could convince local Maori to sell their lands. Masters and his fellow committee member H.H. Jackson tracked to Ngaumutawa paa to meet with Te Korou, who listened carefully to what they had to say. After consulting with his family members he decided it would be to their advantage to have the new settlers on land near his village. His son-in-law Ihaiah Whakamairu (who had married Erihapeti) was dispatched with the small farm proponents on their return to Wellington, to start arrangements for the sale. Retimana did not sign the eventual deed of sale, although he did sign to other sales around Masterton. His family’s names appear on the document however: Karaitiana, Erihapeti and Ihaiah.

Masters was not one of the first settling party of small farmers that arrived on May 2, 1854, but he did arrive shortly afterwards. With his great energy and his determination to “get on”, Masters threw himself into establishing a viable future for himself and his family. As well as successfully farming his small farm he represented the area in the Wellington Provincial Council, and was a vigorous promoter of the Trust Lands Trust. His was a strong influence over the small community that bore his name, a strong influence he jealously guarded until his death in December 1873.

Retimana seems to have ceded leadership of his hapu to his son Karaitiana and his son-in-law Ihaiah. Both father and son became supporters of the King movement in the turbulent years ahead, and Karaitiana spent some time away from Wairarapa, fighting on the west coast. In time Te Korou became reconciled with his pakeha neighbours, and on his death in 1882, many of Masterton’s leading settlers joined in the 300-strong cortege that made its way to his burial place, just metres away from the grave of his old friend Joseph Masters.

The Masterton Stockade – Major Smith’s Folly

Today Queen Elizabeth Park looks quiet and peaceful. The area just north of the rose garden is clothed in closely cropped lawn, spotted with large trees and a quaint memorial, usually called the “Maori Peace Statue.” But hidden underneath the grass are the remains of one of the most remarkable buildings ever erected in Masterton – the Masterton Stockade.

Wairarapa is rightly proud of its record of peace between Maori and pakeha. It was the only district on the North Island in which there was no blood shed between the two races. That pride has sometimes meant some uncomfortable facts have been glossed over, and the willingness of some members of both communities to embark on war-making has been glossed over.

The first period of real tension between the races was in 1863. There were race wars in other parts of the country at the time – especially Taranaki and Waikato – and some of the Wairarapa Maori took advantage of the opportunity to increase their mana in battle. In Wairarapa things got very tense, and there was talk of one of the Kingite followers, Wi Waaka, removing the tapu on Wairarapa and taking up arms, but after much toing and froing, and much drilling by the settler militia and intervention by leaders of both communities, the tension was reduced.

Major John Valentine Smith, leader of the local militia and owner of Mataikona and Lansdowne stations, was not so sure, and he wrote to the Wellington Provincial government recommending the erection of a stockade on the hill behind his Lansdowne homestead. Dr Featherston, the Superintendent of the province, was uncertain however, thinking that the erection of a stockade was as good as an invitation to fight. Local politician A.W. Renall, of a liberal nature and no friend of the conservative Valentine Smith, agreed with Featherston, saying the arrival of the Drill Sergeant in the area had caused excitement, and that stockades would only add to the excitement.

Smith and the militia started building anyway, erecting a flagstaff on the Lansdowne hill they named ‘Mount Direction.’The flagstaff was used as a signal station, a black ball being hoisted when the weather was fine enough for a parade. It was claimed that the ball was visible throughout Masterton.

The Lansdowne stockade was not built however and Major Smith had to wait for his chance to build his redoubt. There was a brief scare in Wairarapa in 1865 as the Pai Marire religion, started in Taranaki by Te Ua Haumene, spread through the country. Many of the Wairarapa Maori were attracted to the new religion, known to pakeha as Hauhau, and at some took it up enthusiastically. One local chief was appointed as apostle to the Ngati Kahungunu peoples. The biggest potential threat to the peace came when a group led by the West Coast chief Wi Hapi was said to be making its way to Wairarapa. Precautions taken included stationing a small troop of the Armed Constabulary, and a similarly small number of militia, in Masterton. The Hauhau were able to pass through the district without any trouble, mainly due to the co-operation of the local Maori.

The events of 1868 were much more worrying, with two major insurrections on the Government’s hands.

The first, and by far the better-known war was being waged on the East Coast. Te Kooti, who had been unfairly imprisoned in the Chatham Islands, escaped and made his way home. The Government pursued him and a series of well-publicised battles took place. At the same time as the Government was fighting Te Kooti on the East Coast it was also trying to deal with Titokowaru on the West Coast.

The Nga Ruahine chief Titokowaru had turned his back on Christianity, and had revived some of the old spiritual practices of his South Taranaki area. He led a strong group of Taranaki people in attacks on the settlers in southern Taranaki, with other warriors from Wanganui and some from other North Island areas including Wairarapa. His avowed intention was to drive the pakeha settlers from the land and to restore Maori mana over their ancestral lands.

The Government became increasingly concerned that a North Island-wide uprising would take place, and local settlers started to feel decidedly edgy. In Wairarapa the two main leaders of the King movement, Ngairo Te Apuroa and Wi Waaka, had both signed oaths of allegiance to the Queen, but there were still those who were interested in Titokowaru’s war.

In a letter sent to Major Valentine Smith, dated September 1868, Thomas Hill, who spoke fluent Maori, advised Smith to inform the Government the local chief Manihera Maaka had recently returned from Titokowaru, but that the rest of the Wairarapa party of warriors had stayed behind to guide a war party through the Manawatu bush. Hill further advised that Maaka was claiming to have been with Titokowaru when the latter ate human flesh, and that Maaka was saying the pakeha of the district would be “struck while they slept.” Smith was clearly worried by this news as he passed the information on to the Defence Ministry, adding that in his opinion there was more “real danger of insurrection” than there had ever been, and that the risk increased as news spread of Titokowaru and Te Kooti winning battles.

Smith, who was from a military family, sought a military solution to the problem, suggesting that the best course of action was to let the local Hauhau, whom he described as a very bad lot, know that the settlers were on the lookout. He proposed the Government should employ 25-30 men as an armed militia on permanent standby.

He also revived his call for a stockade erected in Masterton.

Smith’s proposals were not widely supported. The only newspaper being published in Wairarapa at the time, Greytown’s Wairarapa Mercury, adopted a mocking tone when describing Smith’s plans for both a permanent militia and a stockade in Masterton. With an insight into Maori thought patterns, the newspaper thought the erection of a stockade was in fact more likely to produce war rather then peace in the valley, understanding that the construction of a stockade (or in Maori terms a paa) was an invitation to attack. Events seem to have taken on much of their own momentum from then on.

Many of the districts settlers agreed with the newspaper, and thought the erection of any stockades (Smith had proposed a string of them through the valley) would only incite the local Maori to attack. At a series of meetings called in the main towns they passed a series of resolutions, calling on the Government not to build any stockades.

Tensions between the races were rising throughout the province, however, and the Hutt Valley stockades were garrisoned. The Armed Constabulary officers in Wellington wrote to Smith suggesting that the newly completed Carterton Town Hall could be palisaded, and asked whether it was possible to palisade the Reverend Ronaldson’s house, which was being used as a militia office.

The officers were clearly worried about the state of affairs in the outlying countryside surrounding the towns too. A telegram they sent to Smith said that things in Upper Wanganui were getting worse, and that extra vigilance was called for.

Minister of Defence, J.C Richmond, a personal friend of Smith’s, also sent a telegram, urging the entrenchment of outlying houses in which “settlers may sleep together.”

Major Smith’s long campaign to have a stockade erected in Masterton was about to bear fruit. In late November 1868 Smith forwarded a plan of the stockade he proposed to build in Masterton, and the Government promptly telegraphed back, advising that he should go ahead and commence construction. Smith had already chosen a site near his militia office on part of what was then known as the Cemetery Reserve. The reserve was being leased to prominent Masterton settler Henry Bannister, who agreed to forgo the lease on part of the land, and signed over the use of a piece of land near Dixon Street. The tender of Captain Boys of the Greytown Cavalry to build the redoubt for the sum of £1190 was accepted, and work started on the Masterton Stockade in December 1868. The Government had issued a set of detailed plans for the building of stockades, but Smith had already forwarded his own plans, and had been given permission to build on those plans.

Smith’s plan called for the use of sawn timber, but the Government sent word up that they were worried about the cost of the building, and much preferred that Smith should use “split stuff.” It was thought this would help keep the cost to about £75. Smith was also advised to keep a look out for suitable sites for cheap redoubts and rough blockhouses. The timber for the construction of the stockade was felled and split in Dixon’s Bush, and the slabs were hauled down to the site by William Dixon’s team of bullocks. Once the timber was on site the actual construction was commenced by two cousins, Ted Sayer and Ted Braggins, working as contract labourers for Captain Boys, commander of the Greytown Cavalry.

The plan for the stockade was very simple. It was built as a large square, with double walls, and two rooms at diagonally opposite corners. These rooms (bastions) were roofed and shingled, and were built with loopholes to enable defenders to fire along all four walls from the two rooms. The walls of the redoubt were made of three metre lengths of split totara, about 80 cm thick, which were set 600 mm into the soil. Each side of the wall was actually two walls about 600 mm apart. The gap between the walls was filled with gravel to act as protection against musket fire.

In order for the defenders to fire on any attackers, loopholes were provided at 2m intervals along the walls. A moat, 2.5 metres wide and 2.5 metres deep, surrounded the walls. On the Dixon Street side of the stockade a drawbridge was constructed, operated by a block and tackle.

The agitation against the stockade among the local settlers continued. Richard Collins of Te Ore Ore station started a petition against the building, and politician Henry Bunny called a meeting to discuss the matter. Smith asked his superiors for permission to attend the meeting. He reported back that the meeting wanted 40 Armed Constabulary officers stationed in the district. Collins was telegraphed and told that the Government considered the stockade was needed for the safe custody of spare arms and ammunition, and Smith was told to “go on with the Stockade.”

The Wairarapa Mercury, implacably opposed to the construction of the stockade, suggested that the bastions would never be used to defend the district – instead they thought one would make a wonderful Public Reading Room and the other would be a useful Infirmary. Further to that, they queried how the tender was awarded to Captain Boys without ever being advertised. As the construction was starting the local Maori held a meeting at Ngairo’s pa, near Rangitumau. Ngairo announced that the local Maori had no intention of attacking anyone, but protested against the erection of stockades, and said he considered them a threat.

The Mercury was also scathing about Major Smith. They suggested he developing a reputation for being an alarmist, and sarcastically said that Smith was aware that “with his military skill, his great resources and extreme popularity, his safety is of paramount importance to the inhabitants, and the Maories knowing that so well, would direct the first attack against Lansdowne.”

By early 1869 the work on the stockade was progressing well. Men were employed in removing the gravel from the moat, and the posts were in the ground for the walls. The Mercury continued its attack on the stockade, saying that, given the stony nature of the soil, it was most likely that the whole stockade would fall into the moat. They also complained that the money spent on the stockade would have been better spent on bridges and roads.

By February the building was nearly complete – the outer wall was clad and the inner wall was nearly finished off. Before work went much further however, disaster fell on the builders. Or rather, one of the walls did! The moat was a problem. The crumbly nature of the soil and the steep pitch of the moat meant the moat was constantly wearing away, this erosion making a threat to the walls.

The Evening Post of February 13 reported that the whole of the stockade had caved in the night before. The Mercury could scarcely contain its delight. To make matters worse for the builders it was announced that the collapse had happened in front of a group of important visitors, including militia officers and the local magistrate.

Captain Boys was placed in a dreadful position by the collapse of the wall. He immediately offered to rebuild the wall if allowed to place it a further 600 mm inside the moat. The Government were not happy about the events in Masterton and in March they sent Mr Haughton, Acting Under Secretary for Defence, to inspect the stockade.

Haughton reported back that the structure was mainly built to the plan submitted by Smith, but pointed out that the plan was very loosely drawn and that some important matters were left off the plan.

The walls were a problem. There was no call to mortise the rails into the posts, and the rails had simply been nailed onto the posts, and the slabs were then nailed to the rails. Once the gaps between the walls were filled with gravel the whole weight of the gravel was being held by the two or three nails holding the planks onto their framing. According to his report the stockade was especially vulnerable on the south-west and he said it would “certainly not stand forty-eight hours wind and rain from that quarter.” He recommended that improvements be made to the stockade, which seemed to him to be very rough, because as it was the stockade was “practically useless and will in a short time cease to exist except in the form of sawn and split timber.”

Work stopped on the stockade. The Government would not pay until the work was finished and Boys wanted payment for the extra work he had to do. Smith wrote to the Government on Boys’ behalf but they responded by stating that they would not expend any more money on the building.

The Mercury had the answer. They thought a drain dug from the Waipoua River (then flowing through a channel near Bruce Street) would do the trick, as the next flood in the river would just take the whole thing away. The stockade, “a laughing stock to everyone, European and natives,” was handed over to the Government in late March, and six members of the Armed Constabulary took up residence in one of the bastions. The drawbridge rope had not arrived, and further props were required for the walls to stop them falling in. In their parting shot the Mercury suggested Mr Bannister should be allowed to use the stockade as a shearing shed, or perhaps a boiling-down works. The threat of uprising quickly faded away, and the stockade was never required.

By November 1869 just one man was left, and Major Smith shifted his office from Reverend Ronaldson’s house to the stockade. In May 1870 the last member of the Armed Constabulary, Constable Tasker, was dismissed and Smith was left in sole charge. He wrote requesting a staff member to help keep the militia office secure, but the Government simply wrote back to tell him to lock the door behind him when he left. Major Smith must have had an uncomfortable time in his office. The bastion floors were earth, the windows not glazed, there was no chimney and the whole room must have been cold.

Funnily enough, Major Smith’s folly, the Masterton stockade, was be of some use to the town.

In 1871, 1873 and 1875 the stockade was used as a Showgrounds for the first Wairarapa Agricultural shows, and the bastions were destined to be used as immigration cottages. In late 1873 local magistrate H.S Wardell wrote to the Immigration Department, suggesting some works to make the bastions more suitable for use as an immigration depot. By coincidence the officer Wardell dealt with was the same C.E. Haughton who had written he scathing report on the building some years before.

A further addition was made to the stockade when a two-storied cottage was added to the collection of buildings. The cottage was designed to serve as a Mess Room and Kitchen, and came complete with chimneys. The Mercury (by now called the Wairarapa Standard) was still not impressed – they described the building as “gloomy.”

In 1875 the land the stockade stood on changed hands, the Government handing it over to the Masterton Park Trust, and in 1877 the first plantings in what was to become Queen Elizabeth Park commenced. The Trust leased the stockade to R.I.S. Carver, a local musician, for £15 a year.

By this time the stockade, never a thing of beauty, was a total wreck. The Standard had this to say:- “As an historic momento of the dark ages in Masterton it doubtless possesses an absorbing interest to the antiquarian mind, but like Othello, its occupations gone and destitute of paint, with its windows battered by mischievous boys, and its ponderous drawbridge smashed, it is calculated to excite anything but terror to besiegers!”

The stockade stayed on site until 1882, when the Park Trust sold it at auction. Mrs Annie Ewington bought the remains of the stockade to use as a fence around her Lansdowne garden. She also bought the cottage from the middle of the stockade and shifted it to near the current site of the stadium, where it burnt down in 1900.

The Masterton stockade, built by the Government for over £300 sold for £24 and 10s.

Today all that remains of Masterton’s contribution to the New Zealand Wars are some earthworks in Queen Elizabeth Park, visible in a dry summer, and the Maori Peace Statue, placed on the site in 1921.

Papawai – the centre of the Maori Parliament

In the last years of the nineteenth century, and the first years of the twentieth, Papawai marae, near Greytown, became the focus of Kotahitanga, the Maori Parliament movement, and hosted many important meetings to discuss issues of importance to Maori. The genesis of Papawai lay in the Government purchase of the large Tauherenikau block in the early 1850s. An area of land from the sale was specifically set aside for the creation of a church village in the bush just south of the Waiohine River, and to the east of the Kuratawhiti clearing. The land set aside adjoined the land granted to the Small Farm Association for their settlement of Greytown, and the two townships developed together from 1854.

Three main groups came to live at Papawai at that time, groups led by Te Manihera Te Rangitakaiwaho, Ngatuere Tawhao and Wi Kingi Tu-te-pakihi-rangi. Times were difficult, however, with tensions between the various groups, and before long the latter two chiefs had lead their people away from Papawai again.

The Government had promised local Maori that they would build a flour mill for their use, and the mill was constructed at Papawai but it too became a cause of conflict with Manihera maintaining that the mill was his alone and refusing to allow others to grind their wheat. The Church of England constructed a school at Papawai, drawing on monies from lands donated by local Maori at Papawai and Kaikokirikiri near Masterton. The school, called St Thomas’ was opened in December 1860, but niggardly support from the Government meant the school never thrived, and it closed in the mid-1860’s after local Maori refused to send their children to the school.

The town itself, sometimes called Manihera Town, was also struggling at that time. The missionary William Ronaldson described it as a “small place, not a mile square, surrounded by dense bush, and scarcely fit even for pasture” and said the two-mile road from Greytown often took an hour to travel.

Papawai was in a long decline during the 1860s and 1870s, but by the 1880’s it was starting to assume a more dominant role in Maori society, perhaps reflecting a shift in power among the chiefs.

Manihera had been the main chief of the township during its establishment years. His date of birth is not known but he was a young married man when the Wairarapa Maori returned home from Nukutaurua in the early 1840’s. He was the son of Rangitakaiwaho, and, although descended from both Rangitane and Ngati Kahungunu, was primarily thought of as of the Ngati Moe hapu.

He was a keen supporter of leasing land to sheep owners, and is recorded on many of the first leases. His enthusiasm for leasing was not always appreciated, and he was inclined to ignore the rights of other owners, leading to a number of arguments. On one occasion he was forced to flee into the Tararuas to avoid his own relatives, who were said to be so upset they were talking of killing him. Over the years he became one of the most frequent witnesses at the Maori Land Court, arguing for the land rights of his people. As he aged he looked for a successor to take over the leadership at Papawai, and to develop his vision of the township assuming leadership for Wairarapa Maori.

He chose Tamahau Mahupuku to deal with issues relating to the people, and selected the scribe Hoani Te Whatahoro Jury to take care of land matters and negotiations with the Government.

Tamahau Mahupuku was of Ngati Moe and Ngati Hikawera descent, and is said to have been born about 1840. He was regarded as a handsome but rather wild young man. He married three times, but it was his second marriage, to the widow of the chief Matini Te Ore , that secured his place at Papawai. His appointment by Manihera, and the wealth generated by the hapu’s extensive land holdings, led to his mana increasing, and when Manihera died in June 1885 Mahupuku was his natural successor.

Under Tamahau’s leadership an extensive building programme was undertaken at Papawai. The house Hikurangi was opened in 1888, and three others quickly followed – Waipounamu, named for the people of the South Island; Aotea, for the Taranaki people, and Potaka, after a famed Wairarapa marae.

In 1897 the programme was extended further, with new buildings to accommodate the meetings of the Maori Parliament. The Maori newspaper Te Puke ki Hikurangi was also first published at Papawai in 1897. Although originally intended to publicise the work of the Kotahitanga movement it was also used to deliver a wide range of news, including the publication of tribal history. It was published until 1913.

The Maori Parliament was hosted at Papawai in two separate sessions during 1897. These meetings resolved to support Te Keepa Te Rangihiwinui’s petition to the Queen that all remaining Maori land should be reserved absolutely for Maori, and submissions were made to Government on the issue.

In 1898 Prime Minister Richard Seddon drew up a bill for the administration of Maori land that caused a storm of protest in Maori circles, as it was thought of as being very paternalistic. Tamahau held large hui at Papawai to discuss the issue, which had split the Kotahitanga movement. He found himself at odds with many members over his support of Seddon and the Government. He also supported Seddon’s 1900 Maori Lands Adminstration Act and the Maori Councils Act, both of which seemed to deliver a degree of self-government to Maori.

Tamahau Mahupuku is said to have spent more than £40,000 on various projects and hui between 1894 and 1904, and Papawai hosted most of the leaders of the country, Maori and pakeha. He supported a brass band that played to the thousands that visited Papawai, and was noted as a generous host. Under his guidance many special meetings were held to record the history, whakapapa and customs of the Maori. These meetings were the source of much of our knowledge about Maori life and beliefs.

Tamahau died in 1904. One of his last projects had been the palisading of the marae at Papawai. A number of large totara logs were also gathered, and after his death these were carved into eighteen large tekoteko, carved figures, representing important ancestors. Uniquely, the tekoteko face into the marae to represent peace, rather than facing outwards to confront enemies. The Government financed a large marble monument that was erected at Papawai, commemorating his role in bring the two races together. Tamahau’s death lead to the role of Papawai becoming diminished. No-one could afford the lavish hospitality of the past, and although other leaders arose, none had his financial strength.

The elements played their part in the diminution of Papawai too. The hurricane force winds of October 1934 destroyed the Aotea-Waipounamu complex and the 1942 earthquake destroyed the marble monument to Tamahau. Even the tekoteko suffered from dry rot.

Papawai has undergone a restoration. Tamahau’s monument has been re-erected and a project was initiated in the early 1990s to preserve the few tekoteko that remained. Today there are still Wairarapa ancestors standing watch over Papawai, the seat of the Maori Parliament.

Peace Statue

Te Ore Ore marae was a hive of activity in early 1881. Te Potangaroa, the chief who had built the meeting house Nga Tau E Waru on the site, and who was regarded by many Wairarapa Maori as a prophet, called his people to the marae to hear him tell of a vision he had received. As well as gathering to hear the words of Paora (Paul) Potangaroa the meeting was also to celebrate a meeting held in the same spot in 1841 when a decision was made to follow Christianity.

Thousands of visitors made their way to the marae from early March for the hui on March 16, 1881. A contingent of Napier Maori were met at the outskirts of Masterton and escorted to the marae by the Masterton Brass Band. There were said to be 52 buggies and 60 horsemen and horsewomen in the party. Food was also gathered and stored in an enormous ‘big pyramid,’ said to have been 50 metres long, 3 metres wide and a metre and a half high.

On the 16th Potangaroa unveiled a flag that he had seen in a dream, and asked those assembled to give their interpretation of the flag, which had a deep black border containing sixteen stars in the centre, with chequer work on the right, and clothing painted onto material on the left. Various chiefs came forward with their interpretations of the flag, but there was no unanimity about its meaning. Potangaroa died shortly after this large meeting, and was buried on his ancestral lands at Mataikona. Before he died, however, he made certain predictions about the coming of a new church that would fill the needs of Maori. A covenant was drawn up by the scribe Ranginui Kingi, setting out his prophecies, and sealed beneath a marble memorial stone erected inside the Nga Tau E Waru house, along with various artefacts.

Among the predictions that Potangaroa is recorded as having made was one concerning the coming of a special church for Maori. “There is a religious denomination coming for us; perhaps it will come from there, perhaps it will emerge here. Secondly, let the churches into the house – there will be a time when a religion will emerge for you and I and the Maori people.” Potangaroa also predicted a number of other signs would let Wairarapa Maori know that his prophecy had been fulfilled within the next forty years.

Shortly after this prediction the missionaries of the LDS Church arrived and many local Maori became Mormons, believing Potangaroa had predicted their arrival. Over the years other churches, including Ringatu and Ratana also claimed he had predicted their arrival. Another church, this time a home-grown church, strongly based in Wairarapa, was also to claim that Potangaroa had predicted its coming.

The Church of the Seven Rules of Jehovah was founded by Simon Patete, a Ngati Kuia chief from Havelock, in Marlborough in the mid 1890s. His church, again founded following a prophetic dream, was quickly taken up by Wairarapa Maori and was soon more popular in this area than in its area of origin.

The local leader of the church was the Ngai Tumapuhiarangi chief Taiawhio Te Tau, who was also active in the Maori Council, being Chairman of the Rongokako Council, which covered the area from Dannevirke to Cook Strait. As the church grew in strength in Wairarapa churches were constructed at Tauweru, Mataikona and Homewood. The church at Homewood, known as Manga Moria, has recently been renovated and restored.

In 1921 local Maori realised that the forty year anniversary of Potangaroa’s prophecies was approaching, and that another hui should be held to discuss whether his predictions had come to pass. A hui was called for at Te Ore Ore, in the meeting house Nga Tau E Waru, which still contained the monument to Potangaroa, and his covenant.

The meeting was called by the Rongokako Council. As Potangaroa’s flag flew outside the people gathered for the hui discussed how the advent of Christianity had brought peace to Wairarapa, making it the only area in New Zealand where there had been no blood shed between Maori and pakeha.

The meeting decided to mark the fortieth anniversary of Potangaroa’s covenant by placing another covenant in another monument. This time, though, the monument was to be erected in Masterton Park, rather than at Te Ore Ore. A special statue was commissioned and a large ceremony was held in Masterton Park, at which Taiawhio Te Tau represented the Maori race, and Masterton’s mayor, O.N.C. Pragnell, represented the European race. In the ceremony great stress was placed on the peace that existed between Maori and pakeha in Wairarapa, and the harmonious way that the two races co-existed.

The statue was made of Italian marble, and featured the form of an angel. A special cavity was drilled into the front of the marble plinth holding the angel, to allow for photographs of members of the British Royal family to be placed on show. A cavity was also made in the base, leaving room for a new covenant to be placed inside the monument. The covenant once placed within the monument was not to be seen for another forty years.

Meanwhile other changes were taking place at Te Ore Ore.

The prophet T.W. Ratana had started his movement in 1920 and was gaining many adherents. Many in Maoridom wondered whether it could have been his church that Potangaroa had spoken of in 1881. In 1928 Ratana paid a visit to Te Ore Ore, and while at Nga Tau E Waru removed Potangaroa’s memorial stone from inside the meetinghouse and placed it outside. The covenant, which had been carefully placed inside the monument, had become so damaged as to be unreadable. Fortunately, in 1881 it had been photographed before being sealed inside the marble monument.

About this time Potangaroa’s flag went missing, and shortly after that the loving cup cemented to the top of the Potangaroa monument fell to the ground in the 1931 earthquake. Ratana’s actions in removing the stone, at the request of many Wairarapa people, increased his mana in the eyes of many Wairarapa Maori, and the Church of the Seven Rules of Jehovah lost many of its followers. Taiawhio Te Tau, the bishop of the church, left to become a follower of Ratana.

In 1939 the meetinghouse Nga Tau E Waru burnt to the ground, destroying the famed carvings and drawings it held. A new house was built following World War Two, and named Nga Tau E Waru, in honour of the old house.

As March 16, 1961 approached thoughts turned once again to Potangaroa’s predictions, and to the covenant placed within the stone in what was now called Queen Elizabeth Park. By now the stone was looking a little worse for wear, and over the years it had developed a lean. Local historian Keith Cairns agitated to have a formal ceremony to open the monument, and to update the covenant placed within it, but he could not convince the then Masterton Borough Council.

Eventually the monument was opened, with a minimum of fuss, in July and the covenant was removed from its hiding place in the base. Once again the records were damaged, and the partially rotted papers were taken to Alexander Turnbull Library where attempts were made to repair them. The little that could be read of the covenant made it clear that they had been placed in the base by the members of the Church of the Seven Rules of Jehovah.

At the time of the opening another set of papers was deposited in the base of the statue, there to remain until March 16, 2001, when the monument was once again opened, and the covenant renewed in a special ceremony.

The Eight-Year House

Maori have lived in Masterton district for over 600 years. Until the time of pakeha settlement of majority of tangata whenua lived primarily in coastal areas, although some kainga were to be found in the interior, usually near rivers and lakes.

The closest marae to the township of Masterton is the Te Ore Ore marae on the banks of the Ruamahanga River to the east of Masterton. The principal people associated with this marae are the Ngati Hamua hapu of Rangitaane.

This marae was established in the early 1880s under the guidance of the prophet Paora Potangaroa. There were a number of other marae in the immediate district, perhaps the best-known being Kaitekateka, on the eastern hills in the block known as Okurupatu.

The wharenui at Te Ore Ore was built under the mana of the chief Wi Waaka, with two prophets instrumental in starting the carving, Paora Potangaroa, of Ngati Hamua and Te Hika a Papauma, and Te Kere, from the Wanganui area.

Shortly after work commenced the two men fell out and Te Kere moved away, telling Potangaroa “E Kore e taea te whakamutu I te whare I mua atu I nga tau e waru” – it will not be possible for you to built this house in eight years.

This spurred the carvers on and when the whare was completed within a year Potangaroa called the house Nga Tau e Waru, a reminder of Te Kere’s failed prophesy.

The house was very large – 30 metres long and 10 metres wide – and was decorated in an unusual manner. The front wall, for example, was covered in tukutuku. The heke pipi, the front barge boards, were also unusually decorated with a mixture of carved figures and painted decoration, a blend of kowhaiwhai and carving designs.

When it was officially opened on 5 January 1880 the local newspaper reported that people from as far away as Waikato gathered for the ceremony.

It was in March 1881 that the whare hosted its most important meeting, when Potangaroa unveiled a matakite, a vision in the form of a flag he had made. When he unfurled the flag he asked those present to interpret it. There was a lot of discussion and various chiefs found different meanings in the vision. There was no agreement about its purpose.

Shortly afterwards a group went to Wellington to order a marble monument to be erected in the whare, to mark the meeting and a similar meeting held forty years before. In early April the stone was unveiled inside the house and a few days later Paora came forward to tell his followers they should no longer sell nor lease land to pakeha, they should incur no more debts and refuse to honour old debts.

In 1921 the Wanganui prophet T W Ratana visited the house. A number of locals told him they were uncomfortable with the stone inside the whare. Seven years later Ratana returned and, with the help of a group of especially selected young men, moved the monument from house to the north-east part of the marae. Underneath the monument the prophet found greenstone, a parchment, human bones, and a bottle containing coins.

In September 1939 the whare Nga Tau e Waru burnt down.

The people determined to build a new whare and Te Nahu Haeata, who lived at the Hiona kainga on the other side of the river, was given the job to undertake the carvings. He undertook most of the work, assisted by Hohepa Hutana. The new whare was opened on 28 March 1941. In recent years many of the carvings have been replaced.