Ngatuere gave an account to the Native Land Court of the migration of Ngati Kahukura-awhitia from Heretaunga (Hawke’s Bay) to Wairarapa. Three brothers, one of them Pouri from whom Ngatuere was descended, brought Te Rangitawhanga, a great-grandson of the ancestor Kahukura-awhitia, to his mother’s relatives in Wairarapa. Pouri negotiated with Te Rerewa, Te Rangitawhanga’s uncle, the right to occupy land in exchange for carved canoes. The land included the district where Ngatuere was born, near present day Greytown. Ngati Kahukura-awhitia gradually cleared the forest, until in the time of Tawhirimatea, father of Ngatuere, it had become an open plain.

Little is recorded of the early life of Ngatuere, except the various places where his people lived while he was a youth. By the 1820s, when the northern peoples who had migrated to the Cook Strait coast invaded the Wairarapa region, he was already a major tribal leader. His people were driven from their homes by a war expedition led by Mananui Te Heuheu Tukino II of Ngati Tuwharetoa. His wife’s father was carried off at the battle of Tauwharenikau (Tauherenikau); later, one of Ngatuere’s elder brothers was killed at Te Waihinga by Ngati Toa. Ngatuere was one of the chiefs who escaped after the defeat at Pehikatea about 1834. After this event most of the people of Wairarapa, including Ngatuere, took refuge at Nukutaurua on the Mahia peninsula. Before the flight north, Ngatuere said, ‘they constantly fled from place to place in fear’.

Little is recorded of the early life of Ngatuere, except the various places where his people lived while he was a youth. By the 1820s, when the northern peoples who had migrated to the Cook Strait coast invaded the Wairarapa region, he was already a major tribal leader. His people were driven from their homes by a war expedition led by Mananui Te Heuheu Tukino II of Ngati Tuwharetoa. His wife’s father was carried off at the battle of Tauwharenikau (Tauherenikau); later, one of Ngatuere’s elder brothers was killed at Te Waihinga by Ngati Toa. Ngatuere was one of the chiefs who escaped after the defeat at Pehikatea about 1834. After this event most of the people of Wairarapa, including Ngatuere, took refuge at Nukutaurua on the Mahia peninsula. Before the flight north, Ngatuere said, ‘they constantly fled from place to place in fear’.

They were away about eight years, and then returned after negotiations with Te Wharepouri of Te Ati Awa. At first the Wairarapa people stayed together for mutual protection. Then, as their confidence grew, they began to reoccupy their former lands. Ngatuere and his people went back to the area around Te Ahikouka and Papawai. At this time Pakeha settlement of Wairarapa was just beginning. The region was being explored by surveyors of the New Zealand Company and settlers were looking for land to graze their sheep.

In this situation Ngatuere responded vigorously to challenges to his authority as a person of mana. These challenges came from younger men, more experienced in dealing with Pakeha, such as Te Manihera Te Rangi-taka-i-waho and Raniera Te Iho-o-te-rangi; from the agents of the Crown; and from the missionary William Colenso, who seems to have deliberately affronted his mana. In 1846 Ngatuere received Colenso with kindness at his new pa, Otaraia, on a bend in the Ruamahanga River, just above Lake Wairarapa, but the missionary’s arrogant nature and tone of moral superiority soon led to bitter quarrels.

In 1847 a road was being built from the Hutt Valley north to the place where the town of Featherston would be founded. Colenso feared that his converts in the district, which was part of his ‘parish’, would suffer evil results from working on the road, that they would work on Sundays, and be exposed to the temptations of alcohol and prostitution.

Ngatuere had quarrelled violently with the Pakeha roadworkers and withdrawn his people from the work. But he took the chance to damage Colenso’s reputation by spreading the story that the missionary had warned him that the road would be used by the military to destroy the Maori. William Williams, the East Coast missionary, considered that Ngatuere had tried to discredit Colenso because he had objected to Ngatuere’s allowing a young girl to co-habit with one of the roadworkers.

The relationship between Ngatuere and Colenso grew worse. He refused to go near Colenso’s tent at Kaikokirikiri, north of Masterton, unless a tohunga, whom Ngatuere believed to have killed his daughter, Ani Kanara Maitu, by witchcraft, was sent away. He and his brother Ngairo made Colenso’s work difficult by encouraging horse-racing at Kopuaranga and allowing the young men to drink spirits. At the marriage of Hemi Te Miha, when both men were present, Colenso grossly insulted Ngatuere and Ngairo by tossing aside their gift of tobacco. Smoking, for Colenso, was another moral evil. The enraged Ngatuere vowed he would never allow a Christian minister to settle in his district.

Ngatuere’s frequent rages and acts of violence earned him an unfavourable reputation among settlers who were, however, happy enough to accept his protection when they needed it. W. B. D. Mantell described him as a bully. However, a man of his time and standing would have been under a severe strain in coping with the coming of colonisation. And in fact he did respond positively to those changes, even though an old man. He learned to write fluently in Maori and was capable of dealing shrewdly with Europeans over land matters. He consistently opposed the agents of the Crown who were seeking to buy land, and was able to hold on to his own interests when others were losing theirs. While others failed to protect themselves, he was able to prevent the settler B. P. Perry from occupying a section of the Taratahi block, and to remove C. B. Borlase from his Waihakeke run.

In his later life he was constantly at odds with Te Manihera Te Rangi-taka-i-waho. These clashes began in 1848 when some junior chiefs forged the signatures of Ngatuere and other senior chiefs on a deed purporting to sell the Tauwharenikau block to the Crown. Then in 1852 Te Manihera added insult to injury by allowing his horse to beat those of Ngatuere and Ngairo at the Kopuaranga races. There were differences, too, over land sales, and over the establishment at Papawai of a missionary centre, college and Maori township. The Papawai flour mill, built by the government, became the source of bad feeling between the two chiefs. Te Manihera, determined to be the main patron of Papawai, did all he could to prevent Ngatuere and his people from using the mill. By 1868 Ngatuere had withdrawn his people from Papawai altogether.

The Wairarapa runanga, established in 1859, was also a source of dispute between Ngatuere and Te Manihera. Ngatuere’s brother, Ngairo, had been one of its founders, but Te Manihera was soon seen as its leader. In 1860 a ‘fearful row’ broke out between Ngatuere and some Ngai Tahu over the ownership of the Hurunuiorangi reserve. Te Manihera and the runanga supported the Ngai Tahu claim, while Ngatuere turned to the government for support.

Ngatuere was not wholly opposed to the runanga, or to the King movement and the Pai Marire religion. His brother was deeply involved in all three, and the two seem generally to have been in agreement. He promptly accepted the invitation to attend the Kohimarama conference of 1860, and this induced other chiefs to go, including Te Manihera. In the war that followed Ngatuere kept Wairarapa from becoming another theatre of war. Though there were plenty of land disputes with the government, Ngatuere refused to allow local people, in association with a Hauhau faction, to attack settlers. He took up a pro-government position in order to protect his own and his people’s interests.

A Wairarapa tradition tells that Ngatuere went to meet an approaching, hostile war party, either King movement or Hauhau, in the mid 1860s. He met them 10 miles north of Masterton, and so great were their numbers, his mouth dropped open in surprise. The place came to have the name Mikimikitanga-o-te-mata-o-Ngatuere-Tawhirimatea-Tawhao (surprise on the face of Ngatuere Tawhirimatea Tawhao). It was later shortened to Mikimiki, but a road sign bearing the full name, one of the longest in New Zealand, was erected in 1975. A further tradition records that at the spot where Ngatuere and other chiefs met Governor George Grey to discuss the keeping of peace in Wairarapa, a huge totara post was erected and named after Ngatuere, ‘Poroua Tawhao’.

Although an Anglican clergyman, the Reverend Pineaha Te Mahau-ariki, officiated at his burial, Ngatuere may never have become a Christian. At Native Land Court hearings (with only one late exception) he did not swear on the Bible, but gave an affirmation. He had more than one wife: Te Mapu, the sister of Te Matorohanga, the tohunga and sage, whose knowledge was recorded by Hoani Te Whatahoro Jury; Mere Makarini; and Ani Patene.

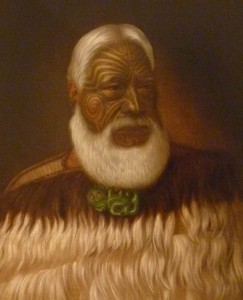

Although he was considered ‘loyal’, and was at one time appointed an assessor for the Native Land Court, he was too independent and autocratic to be appreciated by Europeans. But to his own people he was the embodiment of mana and tapu. He died on 29 November 1890 and was buried near Waiohine, not far from his place of birth. He was survived by four daughters and three sons, of whom two are known: a son, Kingi Ngatuere, and a daughter, Akenehi Ngatuere. A carved figure representing him stands at Papawai.