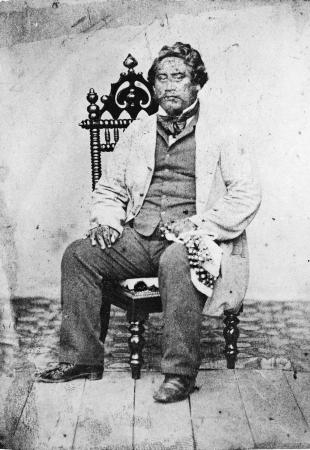

Te Manihera Te Rangi-taka-i-waho

Te Manihera attended William Williams’s mission school at Waerenga-a-hika, near present day Gisborne. While on the East Coast he married Rerewai-i-te-rangi from Tokomaru Bay. In 1841 Pehi Tu-te-pakihi-rangi brought him home to Wairarapa. At this time Pakeha settlers were taking an interest in the sheepfarming potential of the Wairarapa district. Te Manihera’s life was to be greatly influenced by the spread of settlement and pastoral farming.

In the 1840s he was still a young man who had not yet achieved a position of standing. Yet, like many of the younger men in the region, he soon took a leading role in land dealings, in competition both with older leaders and with his own generation. Pakeha regarded him as their staunch friend in the 1840s and 1850s. He eagerly accepted the challenge of the new commercial opportunities created by settlement, and wished to be seen as the equal of older leaders, such as Ngatuere Tawhao, and the new Pakeha gentleman settlers. As early as 1853 he built a large European house; he ran his estates as an individual proprietor, and was noted for his elegant European clothes.

Exploring parties of New Zealand Company settlers and officials visited Wairarapa in 1842 and 1843. In 1844 Te Manihera and two other Maori visited Wellington, staying there with Charles Clifford and William Vavasour. A party of would-be settlers, including these two and Henry Petre and Charles Bidwill, set out with Te Manihera for Palliser Bay and travelled up the Ruamahanga River to Wharekaka and Kopungarara. Te Manihera managed the negotiations for the Maori owners. Two extensive runs were leased at an annual rental of £12 each. Soon Te Manihera and others shifted to Otaraia to be close to their Pakeha.

This was the first of many negotiations in which Te Manihera was involved. Many of them led to quarrels with other leaders whose rights he ignored. He leased land to the settler Archibald Gillies at Tauwharenikau (Tauherenikau) in 1848. His own relatives were so incensed that they talked of killing him, and he was forced to flee for a period into the Tararua Range.

Although by 1853 Te Manihera and other chiefs were earning substantial sums from the leasing of their lands, from that year they consented to the sale of large blocks. Governor George Grey had met the chief objection to sale by guaranteeing that the existing Pakeha lessees could have the first refusal of their homesteads. The district land commissioner, William Searancke, believed that Maori feared that the government would remove them from their lands if they did not sell. In 1852 their missionary adviser, William Colenso, who had always told Maori never to sell, had been removed in disgrace by church authorities, and his influence may have been missed. Over the next 20 years Te Manihera’s name appeared more often than that of any other seller on deeds of sale and receipts.

Much of the proceeds from these sales was frittered away; like many others Te Manihera was lured into debt by traders, and forced to sell more land in order to keep afloat. In spite of his troubles he remained supportive of Pakeha. He was made an assessor in the Native Land Court and in 1853 was host to a public meeting of lower Wairarapa electors in his house at Otaraia. He was himself an elector, through owning land by Crown grant.

In 1854 Te Manihera was the first to sign the deed selling the Kuhangawariwari block from which land was reserved for the Maori township of Papawai. When the town was laid out he apportioned the land; Bishop G. A. Selwyn was granted 400 acres for a Maori college. There were delays (in 1854 there was an outbreak of measles) but by 1855 the government had carried out its promise to erect a flour mill at Papawai. The Reverend William Ronaldson added his support for a township so that he would have a worthwhile congregation. Ngatuere Tawhao, Wi Kingi Tu-te-pakihi-rangi and Te Manihera each led separate groups of their people to settle at Papawai in the late 1850s. But the first two withdrew, after Ngatuere and Te Manihera had quarrelled about control of the mill, and the place became known as Manihera Town. A college, founded in 1860, was not a success and in the late 1860s Papawai had few inhabitants.

Although, in the later 1850s and in the 1860s, some settlers and officials considered Te Manihera to be implicated in both the King movement and Pai Marire, he does not appear to have been a strong supporter of either. He had fallen out with Searancke, and helped destroy the land commissioner’s reputation among Wairarapa Maori by testifying that Searancke had called him a liar. Thus Searancke’s claim that Te Manihera was the leader of the King movement in Wairarapa should be treated with caution. Ronaldson believed that if Te Manihera inclined to the King movement, it was out of dislike for Searancke. In 1859 he supported the government at the King movement meeting at Te Waihenga; and the following year accepted the government’s invitation to go to the Kohimarama conference, possibly to spite Ngatuere. Despite scares among the settlers throughout the 1860s, Wairarapa remained peaceful. Te Manihera’s influence and lack of real commitment to both the King and the Pai Marire movements contributed to this.

Te Manihera was still involved in disputed land deals through the 1860s and 1870s. For example, in 1862 he sold Te Puata (or Taheke) block to the government. On the margin of Lake Wairarapa, this land had been raised above the lake level by the 1855 earthquake; it remained a cause of dispute for years after his death. Then, in 1876, he played a major part in the highly controversial sale to the government of fishing rights in Lake Wairarapa. He induced Te Hiko to go to Wellington on another pretext and there pressured him into consenting to the sale. Te Manihera and Te Hiko fell out over the matter of payment; Te Manihera withdrew from the transaction, with the result that the older man was burdened with the responsibility for it. It became known as ‘Hiko’s Sale’. Te Manihera was one of the most frequent witnesses before the Native Land Court. One of his greatest battles in the court was to persuade it to allow a road to be built through Te Ore Ore block to the coast. He succeeded, but only at the price of earning the enmity of Te Ore Ore people.

In his last years Te Manihera’s vision of Papawai as the political centre of Wairarapa developed its full potential under the leadership of the successor he appointed, Tamahau Mahupuku. To him Te Manihera delegated power to deal with all matters relating to the people, while Hoani Te Whatahoro Jury was to assist with land matters and negotiations with the government. In his old age Te Manihera achieved the status to which he had aspired all his adult life. The controversies were overlooked; he was recognised as a major leader.

For about 12 years before his death on 6 June 1885 Te Manihera had been in ill health, and in low spirits over the death of most of his children. Of the 14 children of his first marriage only 3 survived. All 8 children of his second marriage died before he did. They were all buried at Papawai. He blamed himself for these deaths, believing that he must have violated a tapu. His first wife, Rerewai-i-te-rangi, had died at Gisborne; his second wife survived him.

Great numbers attended Te Manihera’s tangi at Papawai: telegrams announcing his death had been sent to John Ballance, the native minister, to Sir George Grey, to Henare Tomoana, MHR, to Renata Kawepo of Napier, to Henare Matua of Porangahau, and to many of the old settlers in the Wairarapa.