Hoani Paraone (Brown) Tunuiarangi was born probably in 1843 or 1844 in the Whakatomotomo valley near Palliser Bay in southern Wairarapa. It is thought that his father, John Robert Brown, was a whaler, possibly one of John Wade’s men stationed at Te Kopi by 1843. Tunuiarangi recorded his mother’s name as Hine-i-whakaruhia (Ruhi), daughter of Tiramehameha of Ngati Rakairangi, but other information suggests that his mother was Kaipaoe III of Ngati Kahukuranui. He belonged to these hapu, and also to Ngati Hinewaka, to the Rangitane hapu Ngai Tukoko and Ngati Hikarahui, and to Ngai Tahu of southern Hawke’s Bay and Palliser Bay. Although he had lines of descent from Tahu, Ira and Rangitane, he was usually known as a chief of Ngati Kahungunu. His sister was Hera Te Miha, possibly also known as Hine-ki-te-rangi; Puhara and Taiawhio Te Tau were his half-brothers.

Little is known of Tunuiarangi’s childhood or upbringing, except that he was Anglican and literate. His elders, Paratene Te Oka-whare and Aporo Piritaha, were among his teachers in Maoritanga. As a young man in the 1860s Tunuiarangi is said to have acted as guide and interpreter to government forces, and about this time he guided J. G. Holdsworth to the summit of what was subsequently known as Mt Holdsworth. Tunuiarangi was living at the mouth of Lake Onoke, but by 1880 he had moved to Hinana near Gladstone, where he was appointed an assessor of the Native Land Court. He resigned in 1892, possibly as a result of the call by the Kotahitanga movement to abolish this role. Like most of his contemporaries Tunuiarangi spent much time in the Land Court in the 1880s and 1890s presenting his own claims and those of his people. He was listed among the owners of the Wairarapa lakes in 1883, and gave evidence to the commission of inquiry concerning them in 1891.

Tunuiarangi was a representative of Wairarapa Maori at the preliminary sessions of the Kotahitanga movement in the Bay of Islands in 1892; he claimed to have been a supporter of Raniera Te Wharerau’s proposal to use the Treaty of Waitangi to protect Maori and to regulate future relations between Maori and Pakeha. He was a member of the Maori parliament for Wairarapa and a minister in the Kotahitanga government from 1892. Some Wairarapa Maori felt he had not sufficiently supported them in their attempts to retain the Wairarapa lakes, and in the Kotahitanga parliament of 1893 Tunuiarangi supported the findings of the commission which in 1891 had worked out a compromise between Maori and Pakeha. In 1893 he was a candidate for the Eastern Maori seat in the House of Representatives but came second to Wi Pere.

In 1894 Tunuiarangi took the request of his mentor, Hamuera Tamahau Mahupuku, and other Wairarapa leaders to the third Kotahitanga session at Pakirikiri, Poverty Bay, asking for financial support for a printing press to produce a newspaper to promote Te Kotahitanga. He received little support and this rejection may have played a part in changing his and Mahupuku’s attitude to the aims of Te Kotahitanga. In 1893 Tunuiarangi had voted for Hone Heke Ngapua’s radical proposal which sought independence for the Kotahitanga legislature from the governor’s authority. But sometime after 1894 Tunuiarangi and Mahupuku studied the Treaty of Waitangi and agreed that it merely conferred the power of assembly for Maori under authority of Queen Victoria’s government.

This changed perception – that the Maori parliament was an institution bound to co-operate with the government, rather than to exist alongside it as a separate authority – brought dramatic consequences for both Tunuiarangi and the Wairarapa region. In January 1896 Mahupuku and Tunuiarangi obtained an agreement with the government stipulating that in return for the lakes Maori owners would be compensated with a sum of money and the opportunity to select suitable lands elsewhere. Tunuiarangi, now seen by Pakeha as a friend of the government, received his reward. On 22 April 1897 he was appointed captain in a contingent of the Volunteer Force, temporarily attached to the Heretaunga Mounted Rifle Volunteers, to accompany Premier Richard Seddon to Queen Victoria’s diamond jubilee celebration. After training a group of 18 Maori as a guard of honour, he sailed with them to Lyttelton on 27 April. Three days later they embarked for London on the Ruahine. The voyage was spent in training and in composing a waiata in honour of the occasion. The Maori contingent participated in the various official parades marking Jubilee Day on 22 June 1897. On 2 July the colonial troops were reviewed by Queen Victoria, and Captain Tunuiarangi was presented to her. He was given a jubilee medal and a ceremonial sword inscribed for the occasion.

In spite of his stance on the Wairarapa lakes, Tunuiarangi was no government lackey, and had his own political agenda during this voyage. He, Wi Pere and Mahupuku had earlier met James Carroll in Wellington in April, and had suggested that a Maori loyal address be prepared which should include a petition that the remaining estimated five million acres of Maori land be reserved in perpetuity. The petition and address was prepared at Papawai. This document, signed by Tunuiarangi and 17 others, was presented by British MP John M. Denny to Joseph Chamberlain, secretary of state for the colonies, and Tunuiarangi was called to Parliament and invited to explain his concerns. Although he was informed that the British government had no power to intervene, he explained that the New Zealand government would listen if Britain made representations on behalf of the Queen’s Maori people.

The following day Tunuiarangi was advised, probably by a journalist, to publish his petition in the newspapers, and to take copies to distribute in New Zealand to increase the pressure on his government. Seddon, still in London, had a copy of the petition sent to him by Chamberlain, and felt constrained to reply to Chamberlain defending his native policy. The embarrassment Tunuiarangi caused the government had its effect; his petition contributed towards Seddon’s 1898 Native Lands Settlement and Administration Bill, which eventually became the Maori Lands Administration Act 1900.

On his return to New Zealand Tunuiarangi commemorated his role in the stirring events of 1897 by renaming his Pirinoa property along the Whakatomotomo Road Ranana II (London II). Jubilee Day was adopted as a special day of celebration for several years, marked by parades of uniformed Maori volunteer units, in which Tunuiarangi played a prominent part, until enthusiasm waned in 1906. In 1900 Tunuiarangi was transferred to the Wairarapa Mounted Rifle Volunteers at Papawai. Two years later it seems that he retired. Europeans usually referred to him as Major Brown from this time.

Although he remained an Anglican, Tunuiarangi was increasingly influenced by the prophecies of Paora Te Potangaroa, who in 1881 had predicted the establishment of a Maori parliament, the coming of the Treaty of Waitangi to Wairarapa, and the dispatch of a military messenger across the ocean to the British government, which would compel the New Zealand government to adopt measures beneficial for Maori. Tunuiarangi was regarded as – and considered himself to be – the fulfillment of some of these prophecies. Te Potangaroa had also predicted the establishment of a new Maori church; in 1912 Tunuiarangi proclaimed this church, which embraced all Christian sects, to be Te Hahi o te Ruri Tuawhitu o Ihowa (also called the Church of the Seven Rules of Jehovah).

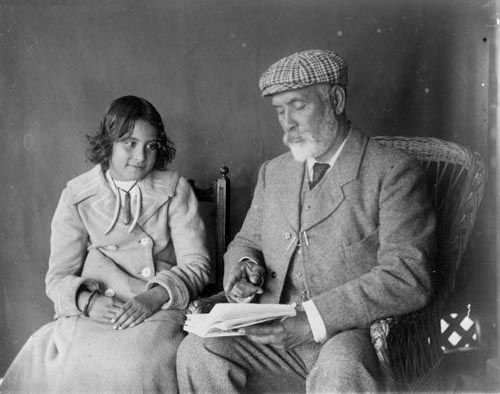

Tunuiarangi was by this time recognised as one of the most influential leaders of Wairarapa and the wider Maori society. He was a member of many committees and councils in Wairarapa and elsewhere, and attended many hui as an influential kaumatua. He established a school at Turanganui, near his Pirinoa property in 1901, was chosen to administer the Wairarapa lake reserves, and in 1907 attempted to interest the government in purchasing part of Whangaimoana in Palliser Bay as compensation for the loss of the lakes. From 1904 to 1906 he was one of five members of the Scenery Preservation Commission. During this period four of his papers were published in the Journal of the Polynesian Society, with translations by S. Percy Smith, a co-commissioner who had encouraged him to become a writer of Maori lore and history. The manuscripts of these and other writings are preserved in various libraries. Tunuiarangi took part in many genealogical discussions and in July 1907 he was chairman of the Tane-nui-a-rangi committee, which worked to preserve and approve books of Maori tradition.

At the death of Mahuta, the Maori King, in 1912, Tunuiarangi was one of several chiefs who spoke at the tangihanga, urging, without success, the King movement to adopt the title of ariki for Mahuta’s successor. During the First World War Tunuiarangi was associated with the East Coast’s war effort to establish a Maori soldiers’ fund, and in 1919 he was a guest of honour at the hui in Gisborne to welcome back the Maori members of the New Zealand contingent. His son, James Carroll Tunuiarangi, had been wounded at Gallipoli. By 1922 he was approaching his 80s and along with many Wairarapa people he joined the Ratana movement, supporting Taranaki Te Uamairangi as the East Coast candidate for the House of Representatives against Apirana Ngata.

Tunuiarangi may have lived in Masterton for a period in his old age, but he returned to his house in Carterton, where he had resided from about 1912. After a lingering illness he died there on 29 March 1933, survived by James and a daughter, Inuwai Te Wharepurangi (Kokiri), the children of his first wife, Tarita Cameron. He may have had a daughter by his second wife, Taiewiwaru, but a third union, with Te Turiraro (Turiaru or Iwiraru), seems to have resulted in no children. He was buried at Hinana.