A BRIEF TIMELINE OF THE WAIRARAPA

The Wairarapa is a large and bountiful region with a long and complex history. Maori oral tradition tells us the area is a part of the huge fish ‘Te Ika a Maui’, hooked and caught by Maui – a Polynesian tupua (super hero). The fish is the North Island of New Zealand. Te Karu o Te Ika a Maui, the eye of the fish, is Lake Wairarapa (Wairarapa Moana) and its mouth, Te Waha o Te Ika a Maui, is Palliser Bay.

The geographically distinctive Wairarapa valley, bounded by the Remutaka (Rimutaka) and Tararua mountain ranges on the western side and the large hills of the eastern coastline, has been shaped by a system of northeast trending faults, which are still very active today. The valley was once covered in giant podocarp forest, of Totara, Miro and Matai in the north and a mixture of forest, fernland, shrubland, some grassland, swamp and lake in the south.

1000 KUPE

The epic journey of the great Polynesian explorer Kupe left ancient names on the Wairarapa landscape, Nga waka a Kupe, the great waka of Kupe is located near Martinborough and Nga Ra o Kupe, located on the South Coast at Matakitaki a Kupe (Cape Palliser).

1200 FIRST SETTLERS

Traces of settlements two centuries after Kupe have been unearthed on the south coast of the Wairarapa. Archaeological evidence tells us that New Zealand’s oldest inhabited dwelling is a whare (house) site located in the Omoekau Valley above Cape Palliser. The residents were proficient gardeners and an intensive walled system of Kumara gardens is still distinguishable today. Their coastal situation gave them access to an ocean teeming with kai moana (sea food) as well as entry onto the coastal highway by waka (watercraft) or on foot.

1600 IWI

By 1600 Rangitane and then Ngati Kahungunu have arrived and settled in the Wairarapa. Conflict and disputes take place between the two iwi, however intermarriage and diplomacy prevail and on the whole, they coexist peacefully in the region. ‘Te Rerewa’, a political agreement negotiated in the 1600’s established an ongoing accord between the two iwi which still continues today.

1642 ABEL TASMAN

‘A large land, uplifted high’ (Abel Tasman)

Abel Tasman, sent by the Dutch East India Company to find terra australis (the unknown Southern Land) sights the Southern Alps. He later anchors in what is now called Golden Bay and then sails for Chile soon after. His passage east takes him along the south coast of the Wairarapa. He names his discovery ‘New Zealand’ and it appears as a ragged new line on European maps.

1770 CAPTAIN JAMES COOK

Tangata whenua (People of the land), Rangitane o Wairarapa and Ngati Kahungunu o Wairarapa, had been settled throughout the region for several centuries, living with relative ease and making use of the Wairarapa’s rich resources when Captain James Cook sailed up the coast in 1770. Ancestors of the south coast hapu Ngati Hinewaka ventured out to Cook’s ship, Endeavour.

“Canoes came off to the ship wherein were between 30 & 40 of the Natives who had been puling after us for some time; it appear’d from the behaver of these people that they had heard of our being upon the coast, for they came along side and some of them on board the ship with out showing the least signs of fear: they were no sooner on board than they asked for nails but when nails were given them … (it) was plain that they had never seen any before, yet thay not only knowed how to ask for them but knowed what use to apply them to and therefore must have heard of Nails which they called Whow, the name of a tool among them made generally of bone which they use as a chisel… ” 1955, Beaglehole J.C. (ed) The Journals of Captain James Cook, Vol. 1 pg178, Cambridge

The locals exchanged koura (crayfish) for the nails.

1820

The arrival of pakeha eventually had a devastating effect on the Maori population of the Wairarapa. A number of war parties from the far north, recently equipped with muskets obtained from pakeha, passed through the region in the 1820s, killing and eating a large number of local Maori.

1830

In the early 1830s, members of the Taranaki tribes who had recently arrived and settled in the Wellington area followed the first wave of intruders into the region. After a series of skirmishes that went the way of the musket carrying aggressors many Wairarapa hapu decided to withdraw to the Kahungunu ancestral homeland at Nukutaurua on the Mahia Peninsular. Some Rangitaane hapu joined relatives in the Manawatu, while others, of both iwi, chose to withdraw deep into the Wairarapa bush and wait.

1839

In England the ambitious Edward Gibbon Wakefield has plans to colonise New Zealand. With others he starts the New Zealand Company and they send the Tory to explore New Zealand’s investment potential.

1839

Explorer Charles Heaphy sees Lake Wairarapa from a Rimutaka ridge.

1840

William Deans and Ensign Abel Best are the first Europeans to trek around the coast to ‘Widerup or Palliser Bay’. Robert Stokes crosses the Rimutaka Range in 1841 and Charles Kettle travels through the Manawatu Gorge and down through the Wairarapa in 1842.

1840

6 Feb, New Zealand’s founding document ‘The Treaty of Waitangi’, is signed.

1841

‘Te Heke o nga Rangatira’, a peace treaty between the Wairarapa rangatira Tutepakihirangi and the occupying Te Atiawa rangatira Te Wharepouri sees the return of the local iwi to their homelands. At the same time the first New Zealand Company settlers, attracted by extravagant promises of work and a chance to buy land, arrived at Port Nicholson (Wellington) and began casting their eyes over the broad Wairarapa valley, assessing its potential as pastoral lands for their herds of sheep.

1843

Access to pastoral land is almost impossible around the southern coast and the New Zealand Company’s surveyor Samuel Brees sets out to find an overland route to Wairarapa and Hawkes Bay.

1843

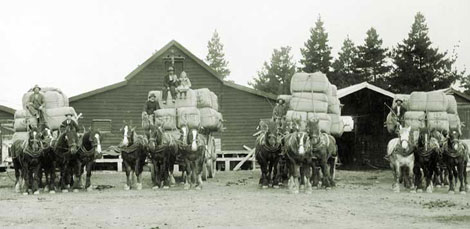

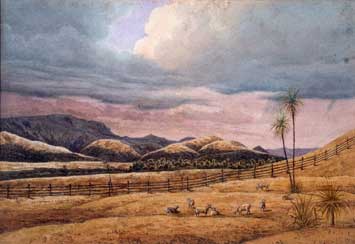

Meanwhile, pioneering settlers drive 350 merino sheep around the rugged rocks of the southern coast and begin the development of some of New Zealand’s largest sheep stations. Frederick Weld, Charles Bidwill, Charles Clifford, William Vavasour and Henry Petre arrange 14 year leases with the Ngati Kahungunu rangatira Te Rangi-taka-i-waho. Charles Clifford’s station ‘Wharekaka’ is the first sheep station in New Zealand. Unknowingly the five grazier farmers put in place the framework of the future shape of the Wairarapa.

1845

The Crown threatens military action and confiscates eighty thousand acres at Maungaroa (White Rock) after an incident involving settler Billy Barton’s staff and rangatira Te Wereta Te Kawekairangi.

“I would not allow them to feed their sheep upon my land and enrich themselves at my expense.” Te Wereta Te Kawekairangi, 1845

1850s – 1860s

Land Purchase

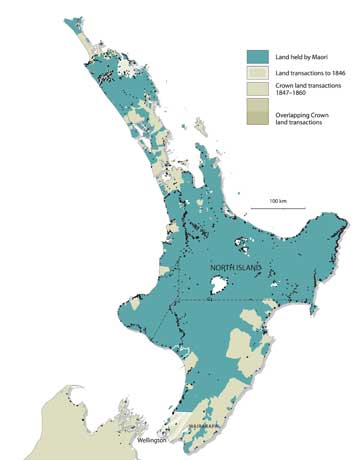

During 1853 the Government’s agent Donald McLean negotiates with Wairarapa chiefs to buy land. The huge Castlepoint block of 250,000 acres (100,000 hectares) is the first of many sales this year. Later known as ‘Ahiaruhe’ this block was purchased for £2500 (approx $1 for 30 acres) and was the basis for some of the largest stations in the north eastern Wairarapa. In total about 1.5 million acres (600,000 hectares) were purchased within six months.

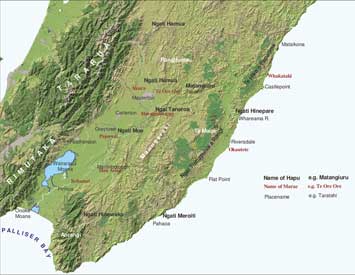

1856 Map

1853

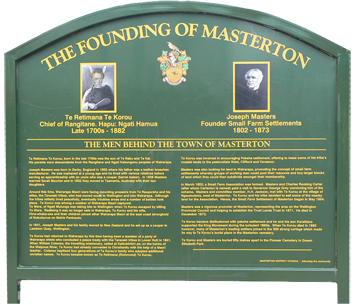

Working class settlers feel cheated by the New Zealand Company and demand land for farming. With Governor George Grey’s support, Joseph Masters, Charles Carter and William Allen form the Small Farms Association in 1853, which buys land through local rangitira Retimana Te Korou. Masterton and Greytown become New Zealand’s first planned inland towns; Carterton and Featherston follow in 1857.

1855

A huge earthquake changes the landscape throughout the Wellington region, raising parts of the coast and creating the western shore access between Wellington and the Hutt Valley, and the distinctive faultline terraces from Palliser Bay northwards along the western foothills of the Wairarapa.

1851

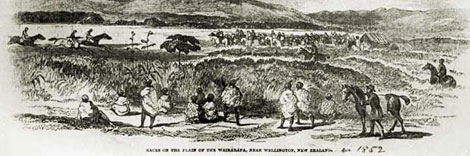

The first race meeting is held on New Year’s Day at a bend in the Ruamahanga River “with some degree of spirit and éclat”.

1853

Six years of work begins to improve the hazardous Rimutaka hill track.

1856

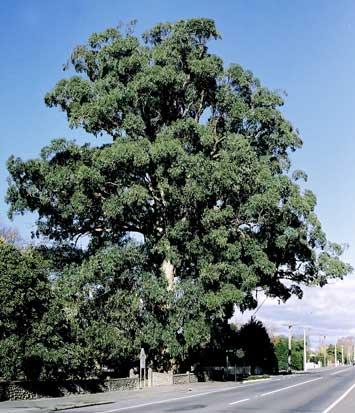

Samuel Oates and a colleague manhandle a huge wheelbarrow laden with goods over the Rimutaka hill from Wellington. The goods are destined for Charles Carter’s property. While the two men are recuperating at the Rising Sun Hotel in Greytown (demolished in 2007) some gum tree seedlings go missing from the wheelbarrow and are later planted around the town. The only survivor is the enormous Eucalyptus regnans beside St Luke’s Church.

Sam Oates’ Gum Tree

Land Wars

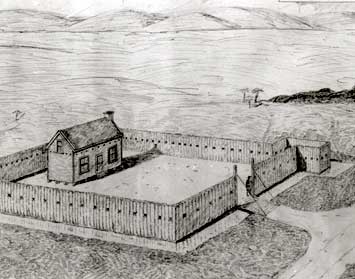

Tensions spread throughout New Zealand and the region as war ignites between Maori and Europeans over land in Taranaki and Waikato. Some land sales are disputed and the Kingitanga movement (Maori King movement) gains supporters. Against official caution and editorial scoffing a stockade is constructed across the road from where Aratoi sits today and Maori fortify a pa in the Ruamahanga valley. Calm leadership on both sides allows peace to prevail and the Wairarapa is the only North Island district to avoid armed conflict during a period which saw a large loss of life in other parts of New Zealand.

Masterton Stockade

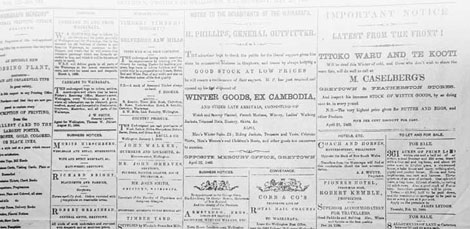

1867 January 5th – Greytown brothers Edward and Charles Grigg publish the first newspaper in the district, the Wairarapa Mercury, printing three issues a week. Journalist and editor Richard Wakelin takes over the business, and in August 1872 it becomes the Wairarapa Standard.

By 1860, three quarters of New Zealand’s exports are wool. With land licences ending wild competition for freehold land often involves dubious methods. Fifty people buy most of the 750,000 acres of ‘five shilling’ Crown land available in the Wairarapa.

1859

Tamahau Mahupuku begins writing down his tribal history while on a shearing run. This written history became a crucial and important part of New Zealand’s recorded Maori history. It is still used as a reference by Maori scholars today.

1859-61

Gold discoveries in Buller and Central Otago draw massive numbers of speculators. The first Cobb and Co coach service runs from Dunedin to the Gabriel’s Gully goldfield and the first gold shipment leaves for London in 1862. Large numbers of Wairarapa stock are sent south to feed the miners. Meanwhile in the Wairarapa people seek leisure, roads are slowly improving and the first cricket matches are organised.

1862

The s.s. White Swan, carrying a number of the country’s leading politicians and civil servants, is holed on a rock off the Wairarapa coastline. Miraculously, no lives are lost.

White Swan Disaster

1860s

The Ngati Kahungunu tohunga Te Matorohanga passes on his knowledge of history and traditions. Hoani Te Whatahoro Jury will later transcribe these stories, and Tamahau Mahupuku and others will help the ethnologist S. Percy Smith to translate them into English. The transcripts and translations are to become an important record of early Maori history.

1870s – 1880s

Breaking New Ground

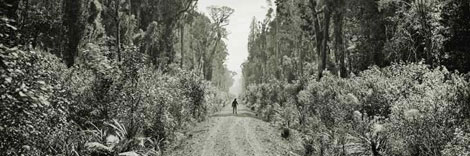

Prime Minister Julius Vogel’s settler development programmes include clearing the ancient forest Tapere nui a Whatonga (The Great Domain of Whatonga), also known as ‘Seventy Mile Bush’, between Masterton and Hawke’s Bay. Danish and Norwegian road-workers clear the Forty Mile Bush up to the Manawatu River in return for cheap land. The first group of settlers reaches the Kopuaranga ‘Camp’ in 1872, and then endure two years of appalling conditions in crude huts until the Mauriceville and Eketahuna settlements are cleared.

1871

The Masterton Trust Lands Trust is formed to manage land not taken up by settlers. The original £3165 value of the land will grow into assets worth over $40 million and the Trust will play a key part in Masterton’s future. The Trust still maintains an influential role in the development of Masterton today.

Deed of mortgage to P.I.L.A.

1878

The Rimutaka Incline railway is opened. One of the world’s steepest railways it uses imported Fell engines built in Bristol in 1875, with special brakes and wheels that grip an extra central rail. It replaces coastal shipping as the district’s main southern transport route.

Fell Engine on Rimutaka Incline

1871

The new Wairarapa and East Coast A&P Association holds a show at the stockade in what is now Queen Elizabeth Park. For several years the venue alternates between Masterton and Tauherenikau.

1873

Wairarapa Permanent Loan and Investment Association is founded in Greytown. It is one of the earliest building societies in the country. It will later become Wairarapa Building Society.

1874

The Manawatu Gorge road opens and ‘The Junction’ at Woodville becomes a base for road construction teams.

1876

James Bragge photographs memorable images recording Wairarapa’s development.

1877

Masterton Park is planted. Later it is renamed Queen Elizabeth Park after her visit in 1954.

1879

Selina Sutherland’s forceful influence leads to the founding of Masterton Hospital.

Selina Sutherland

New Markets Beckon

With low wool prices and world depression, experimental shipments of refrigerated meat to the UK creates excited interest. The first chilled meat and dairy products leave Port Chalmers for Britain in 1883. Many farmers invest in the Wellington Meat Export Company and 25,000 Wairarapa sheep are killed and processed there in 1886, the number doubling in 1887. Our provision of protein to the world has begun.

The exporting of butter and cheese from New Zealand had already begun however when refrigerated shipping arrives, farmers form dairy co-operatives to supply the British market. Greytown opens the fourth factory in the country in 1883. By the 1920s the region has over 1500 dairy farms with about 100 dairy factories and creameries.

Parkvale Dairy Company 1904

1881

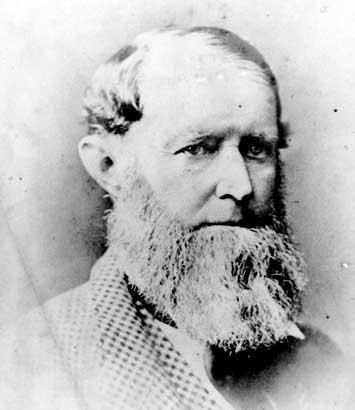

Patriotic Irishman John Martin creates Martinborough, the Wairarapa’s only successful private town, after surveying 593 sections off his 34,000 acre Huangarua station. A recent world tour is Martin’s inspiration for street names and the street layout is based on the design of the Union Jack. For another century Martinborough will be a service centre for the big sheep stations.

The Honourable John Martin

1880

The railway line is extended to Masterton. It will be another 17 years before it can be pushed through the northern forests to Woodville, linking with Hawkes Bay and Manawatu.

1881

Pahiatua begins as a farming village. More people move up from Masterton.

1885

Census returns show the Wairarapa population at 7930 people

1886

Wairarapa Rugby Union is formed with green and black colours, defeating NSW in 1888

Wairarapa Rugby team 1886

1888

The Mount Bruce Forest Reserve is formed to protect a surviving remnant of the original Seventy Mile Bush, Tapere nui a Whatonga (The Great Domain of Whatonga).

1890s – 1900s

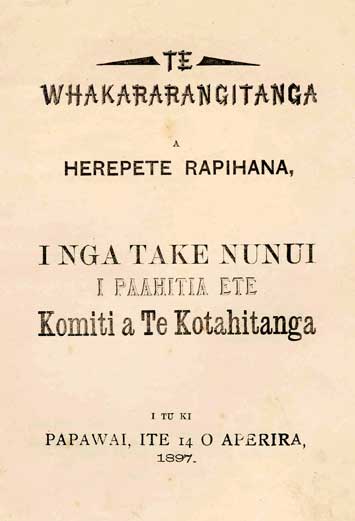

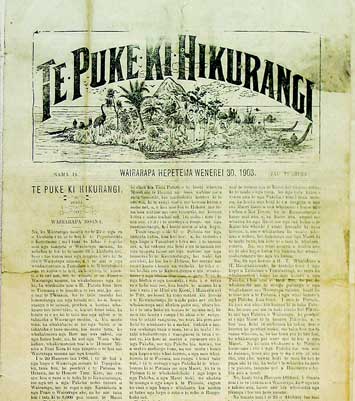

Kotahitanga – Maori Parliament

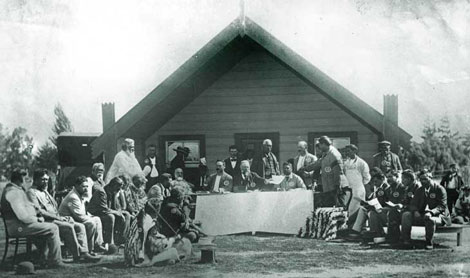

Delegations from many tribal areas meet at Papawai Marae near Greytown to discuss important issues at the Kotahitanga. After talks with Premier Richard Seddon and King Mahuta in 1897, the Maori Parliament supports a petition to Queen Victoria that all remaining Maori land should be protected.

Opening of Aotea-Te Waipounamu

1897

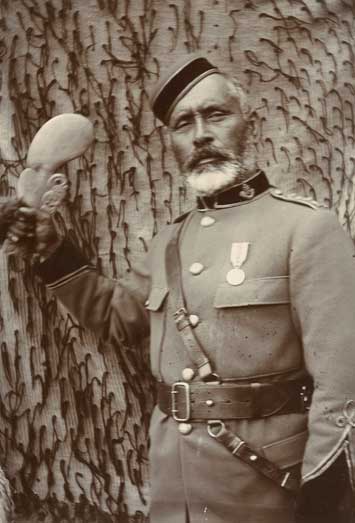

H.P. Tunuiarangi (Major Brown) was made a Captain in a contingent of the Volunteer Force to accompany Premier Richard Seddon to Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee celebration. On 2 July the colonial troops were reviewed by Queen Victoria, and Captain Tunuiarangi was presented to her. He was given a Jubilee Medal and a ceremonial sword inscribed for the occasion.While in London he petitioned for the remaining estimated five million acres of Maori land to be reserved in perpetuity. The petition and address was prepared at Papawai.

1882

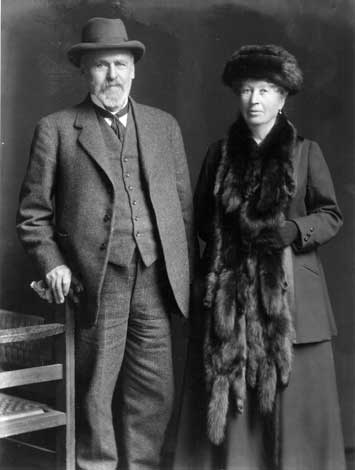

William Beetham and his French wife Hermanze planted a few grapevines at their Masterton home. By 1897 the Beethams own a commercial vineyard, producing about 1850 gallons from mainly Pinot and Hermitage grapes. Visiting in 1895, Australian viticulturist Romeo Bragato finds their Pinot Noir outstanding.

William and Hermanze Beetham

Lower valley farmers have pressured the Government for thirty years to flood-proof land around Lake Wairarapa. After many contentious meetings, Ngati Kahungunu leaders agree in 1896 to cede the lakebed to the Crown. Maori were promised a fishing village at Lake Ferry but instead settled for 30,000 acres of steep hill country in Waikato, in 1906, but access to the important tuna (eel) fisheries that Maori knew for 800 years will not survive.

1890

Greytown initiates Arbor Day in New Zealand, with a decision to plant trees instead of felling them. After a street parade people plant 150 conifers and fruit trees. Some still stand at Greytown’s southern entrance.

1897

The railway reaches Woodville to connect with the Hawkes Bay-Manawatu line.

1897

One of the first x-ray machines in New Zealand is installed at Doctor William Hosking’s surgery in Masterton.

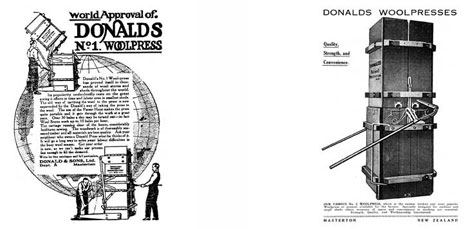

Steady On

Farmer-inventor Donald Donald patented his ‘Solway Eccentric Grip Wool Press’ in 1887 and Donald Presses begin production in 1900. The later Perry Street factory will survive three fires with its innovative American sprinkler system. Exports to Britain, America and South Africa begin in 1905. By the 1980s Donald presses will be sold in 40 countries.

1901

Nireaha Tamaki, a Wairarapa rangitira wins an important Privy Council case and Maori customary law is upheld after a dispute over 5000 acres at Seventy Mile Bush. Nireaha’s victory established that traditional Maori land ownership did exist and should be recognized in court decisions.

1904

After Tamahau Mahupuku’s death, carvers at Papawai Marae transform large totara logs into eighteen tekoteko or guardians, representing important ancestors. Uniquely (in New Zealand), they are installed facing peacefully into the marae and not outwards confronting enemies.

Ideal soils and climate will make Greytown famous for fruit-growing. Between 1904 and 1908 Walter Tate, James Hutton Kidd, D.P. Loasby, Greytown Fruit Growing Company and the Skeet brothers plant the five original orchards, mainly in apples, pears, cherries and small fruit. Kidd’s apple breeding skills later produces the world-famous Gala apple.

James Hutton Kidd in his apple pack house

The Prohibition movement gains strength. Concern grows over social problems caused by alcohol and more people ‘take the pledge’ against the demon drink. In a close referendum, Masterton votes to ‘go dry’ in 1908. Bars close and grapevines are pulled out, ending several successful vineyards.

Picking grapes at Gladstone

1900s – 1930s

The Greatest Sacrifice

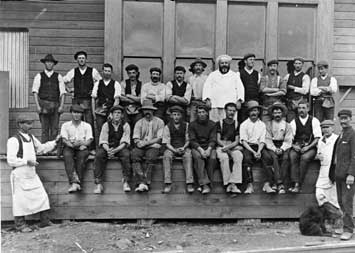

4 August 1914, New Zealand unites to support Britain’s declaration of war with Germany and thousands of young men sign up for the biggest adventure of their life. Many perish and communities throughout New Zealand are devastated by the loss. New Zealand’s largest military training camp is constructed near Featherston in January 1916. Housing up to 7500 men, the 252 buildings are constructed and finished in only five months. Over the four year period about 35,000 soldiers will march from the camp over the Rimutaka hill to board troopships for Europe.

Featherston Military Training Camp

1911

Waingawa Freezing Works opens, processing sheep and cattle formerly transported to Wellington plants. Waingawa will be Wairarapa’s largest employer for most of this century.

Sincere attempts to amalgamate or alternate the two A&P shows have failed; parochial attitudes and resource duplication will continue. Needing more space, Masterton A&P Association buys 75 acres at Solway for new showgrounds, and builds a beautiful grandstand. Their first show at the Solway grounds is held in 1911.

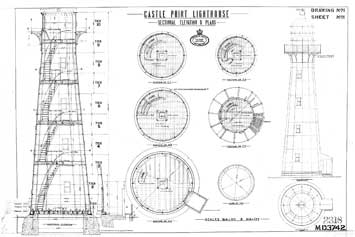

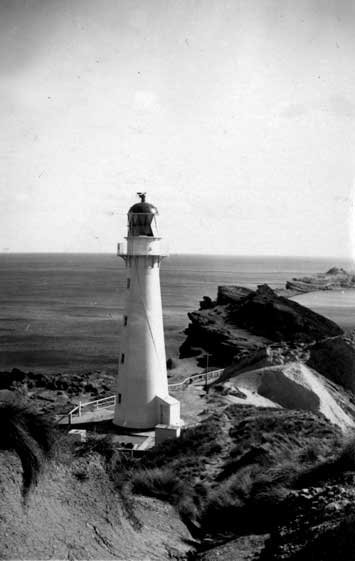

Castlepoint lighthouse plans

1913

The Castlepoint lighthouse is completed. Until 1900 Wairarapa’s dangerous coast has captured about 40 ships.

Castlepoint lighthouse

Percy Fisher constructs the first New Zealand built plane and then makes the first ‘controlled’ flight in the Wellington region at Gladstone.

Meanwhile, the first truck comes over the Rimutaka road.

1918

An influenza pandemic sweeps the world, and in Wairarapa 400 people die. Antibiotics have not been discovered. Temporary hospitals are set up when Masterton hospital overflows, schools are closed and 2000 men from Featherston Military Camp are hospitalised. 177 young soldiers die.

Prosperity and Hard Times

1923

The Kourarau power station opens after the formation of Wairarapa Electric Power Board. It generates about 700 kw and serves about 400 consumers. By 1930 the scheme is linked to the national grid.

Times are hard and Wairarapa churches establish children’s homes. The first to open is the Methodist Children’s Home (1921-78). The Salvation Army uses A.P.Whatman’s bequest to build its Cecilia Whatman Home (1925-80). Sedgley Anglican Boys’ Home (1926-88) and its 15 acre training farm takes boys, many from Lower Hutt.

Whatman Home

1928

British meat company Thomas Borthwick and Sons buys the Waingawa Freezing Works. They already own or use a number of freezing works in New Zealand and Masterton will be their New Zealand headquarters from 1930 to 1958.

1922

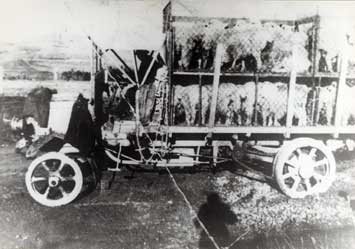

The first double-decked sheep truck in the country, thought to be the first in the world, is designed and built at Riversdale for Masterton carrier F.B. Gray.

First double decked sheeptruck

1925

The census records Wairarapa’s population at 22,424 people.

1927

Hawkes Bay supporters make up almost half the 10,000 rugby fans at the Ranfurly Shield ‘Battle of Solway’ match. Hawkes Bay won.

The Sugarbag Years

Share prices plunge and unemployment spreads after the 1929 Wall Street ‘crash’. Men desperate for work spend many grim months at relief work camps and children go shoeless in sugar-bag clothes. Council projects such as straightening the Waipoua River offer welcome work for some.

A nor-west gale of hurricane force damages many buildings between Greytown and Masterton on 1 October 1934. Papawai’s historic Te Waipounamu Aotea complex is seriously damaged and later it is pulled down. Near Carterton the strong wind blows over a bus full of passengers.

1937

Radio pioneer Ray Cunningham imports kerosene fridges. Through the 1940s and 50s his firm produces cabinets for HMV, Charles Begg and Norge.

Cunningham’s factory

Rebuilding after a 1957 fire, dishmasters, automatic washing machines and fridge-freezers follow. In 1963 N.R.Cunningham Ltd is one of Wairarapa’s two biggest employers, with 300 staff.

1937

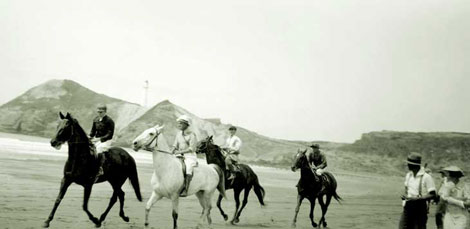

The Castlepoint Racing Club is formed. The first beach races were held in the 1870s, mainly for farm workers. By the 1950s the races will be a well known annual event.

1940s – 1950s

World War II 1939-45

Featherston Military Camp is reopened to house 800 Japanese prisoners of war. On 25 February 1943, 48 Japanese POWs and one guard are killed by gun fire when a violent incident erupts at the camp. Attempting to avoid retaliation from the Japanese war machine that has swept through the Pacific, newspapers wait until 1945 to report it.

Japanese POWs gardening in Greytown

American troops on leave are camped at Memorial Park and Solway Showgrounds from1942 to1944. Having the ‘Yanks’ in town relieves the general worry for many and introduces an air of Hollywood to the area.

ANZAC Hall Featherston, Victory Ball

After prohibition is lifted in 1946 Masterton Licensing Trust is formed in 1947, the second in New Zealand. Profits from liquor sales go to improving facilities and supporting community projects. The Trust continues today and is a strong supporter of Aratoi.

1949

Promising Department of Agriculture trials prompt some Tinui farmers to try aerial topdressing in 1949. Over 18 days three modified Grumman Avengers spread 120 tons of superphosphate across 1000 acres of hill country. Results are impressive, more farmers build airstrips and daring young men in low-flying planes begin to transform marginal land to productive pasture.

Aerial topdressing

Half Gallon Quarter Acre

Pavlova Paradise

1942

June 24 at 11pm a devastating earthquake rocks Wairarapa. Masterton is worst-hit and chimneys fall everywhere with over 200 aftershocks before morning. There are no deaths, but St Matthews Church and several commercial buildings have to be demolished.

1944

The old Pahiatua racecourse, originally set up as an internment camp for European nationals, becomes a refugee camp for 733 Polish children. The plan is for them to return home after the war, but after Russia enters Poland they stay on to become New Zealanders.

Polish refugee children and New Zealand soldiers

1954

Local amateur golfer Bob Charles wins the New Zealand Open golf tournament. He wins it again in 1966, 1970 and 1973. He wins the British open Championship in 1963 and is awarded the OBE in 1972. The local boy becomes Sir Bob Charles, international golf legend!

1955

The Rimutaka Incline closes and the Fell engines are retired when the 8.8km Rimutaka rail tunnel opens, the second-longest in the country. Construction teams began work in 1951 using the latest tunneling machinery and ‘holed through’ 14 months ahead of schedule. The tunnel cuts an hour off travelling time to Wellington by train, making future commuting a possibility.

The Korean War pushes wool prices higher, meat and dairy exports to post-war Britain boom and Wairarapa is prosperous. As the ‘rural rump’ fattens, the region’s economy benefits too. The Government helps many returned servicemen onto ‘Rehab’ ballot farms, and manufacturers like Cunninghams flourish.

Sports and tourism promoter Basil Bodle buys Riversdale Station’s coastal block in 1954, quickly selling sections at Riversdale Seaside Resort. The Surf Club starts in 1956, and with community help a nine-hole golf course opens in 1960. The development attracts more people to the area; power and phone lines and better roading follow. In 1971 a beachfront bach costs approximately $5000.

1950s

‘The 20,000 Club’ is formed to work on increasing Masterton’s population to city status.

1960s – 1980s

A Yard Of Purple Ribbon

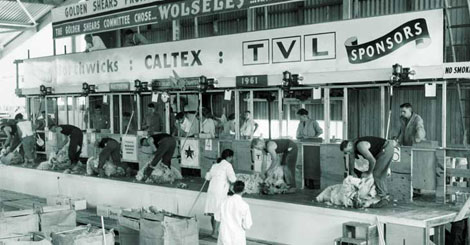

1961

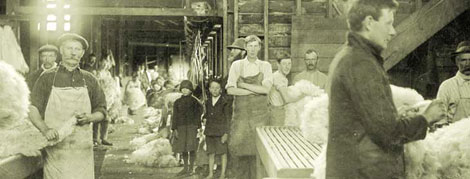

Huge crowds enjoy the first Golden Shears competition. The ‘Shearing Olympics’ begin and legends such as Bowen, McDonald, Potae, Quinn, Ngataki, Fagan and Te Whata are born. By the end of the century the volunteer-driven phenomenon will be the world’s biggest shearing and wool-handling competition.

Four people are killed and five suffer serious burns in Wairarapa’s worst industrial accident, when explosions cause a fire at the General Plastics factory in April 1965. The 7000 square foot button plant crumples ‘like a deck of cards’, and windows shatter hundreds of yards away. Fortunately, most of the 70-80 staff are in the canteen when it happened.

General Plastics fire

In Masterton’s biggest state housing project 300 homes are built on the ‘Cameron block’. Ngati Kahungunu community leader Dick Himona successfully lobbies the Government to allocate some of these houses to Maori. In 1998, half a century after the first state house was built, the Government sold 576 Masterton state houses to Trust House.

In 1963 the ambitious Lower Wairarapa Valley Development Scheme initiates 40 years of flood control work. There will be 200km of stopbanks, floodways to carry water into the lake and more than 100 flood-gated culverts to drain farmland. The Ruamahanga Deviation Scheme opens in 1967, allowing farmers to develop more land on Lake Wairarapa’s eastern shore.

1963

Masterton hosts the Golden Games and a life-saving Carnival is held at Riversdale.

1966

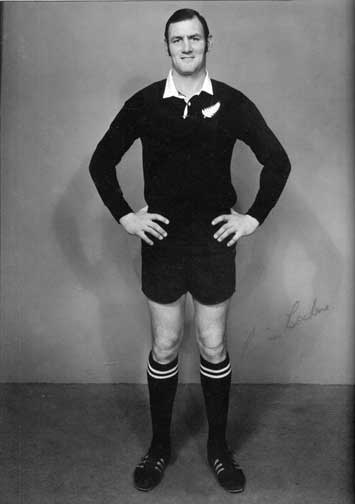

July 16, local rugby icon Brian Lochore captains the All Blacks against the Lions in Dunedin, replacing rugby legend Wilson Wineray. Lochore captained the All Blacks until 1970.

Brian Lochore

1968

‘Man oh man I vos free!’ Latvian Barrett / Barnis Crumen or ‘Russian Jack’ dies. The last of the swaggers who roamed Wairarapa, many rural people have affectionate memories of this fiercely independent, courteous man.

Russian Jack

1969

Masterton Trust Lands Trust builds the Wairarapa Arts Centre, at a time of increasing professionalism in New Zealand art museums.

Coming Together

The coming of milk tankers and uniform marketing has led more dairy co-operatives to merge. Formed in Pahiatua in 1956 the Amalgamated Dairy Co. merged with Masterton and Mangatainoka/Kohinui to form the Wairarapa Amalgamated Dairy Co. This then merged with Ruahine Dairy Co. in 1975 to form the Tui Co-operative Dairy Co.

Manufacturing grows with decentralisation. Alcatel makes car wiring systems, a Philip Morris cigarette factory opens and Government Print moves the telephone directory operation to Masterton.

1975

Masterton Trust Lands Trust’s energy and vision sees the Wairarapa Communtiy Action Programme (CAP) established. In 1989 CAP becomes Wairarapa Community Polytechnic, later absorbed by UCOL.

1977

Greytown Rotary holds the first Martinborough Fair. The 35 stalls increase to nearly 500 by 2007, with crowds of 35,000 or more filling the small town square. The fairs provide funds for Rotary’s projects and involve large numbers of volunteers.

Martinborough Fair, 1977

Falling Apart

1984

The Muldoon Government, faced with growing debt and a high New Zealand dollar, removes Supplementary Minimum Prices (SMPs) and other incentives. Those with big mortgages are hard-hit, farm workers lose their jobs and rural communities are broken as people seek work in town.

1984

Four vineyards, Ata Rangi, Dry River, Martinborough and Chifney begin planting grapevines into the ideal Martinborough soil. Three opt for Pinot Noir and ten years later they are producing world class wine. By 1995 the area’s 17 wineries, Toast Martinborough festival, international accolades and increasing foreign investment have reinvented the town.

1984

Local referee Bob Francis umpires his first major international rugby game, England versus Australia, at Twickenham.

Mayor Bob Francis

1981

Coached by Brian Lochore, Wairarapa-Bush wins Division Two of the National Rugby Championship. They are in Division One from 1982 until 1987, and when Lane Penn coaches the team to a fourth place in the Division One competition in 1985, their supporters’ Christmases have all come at once!

1986

The National Wildlife Centre is created at Mt Bruce Forest Reserve.

1986

Bob Francis is elected Mayor of Masterton. He goes on to become the longest serving Mayor in the Wairarapa, stepping down in 2007 after 21 years.

1987

The over-excited share market crashes after five years of hysterical speculation. The domino effect hits Wairarapa investors

1990s – 2000s

Multinationals and a Transexual Mayor!

1990

The giant Waingawa Freezing Works closes. The financial and social impact is devastating for staff, seasonal workers and Wairarapa’s already staggering economy.

1991

Japanese owned Juken Nissho’s $60 million sawmill and laminated veneer plant is constructed near Masterton.

1992

The Warehouse opens its first Masterton store and McDonalds opens on the former site of Aratoi’s Wesley church. Multinationals and ‘Big Box’ retailing come to town putting pressure on long established local retailers.

1995

Georgina Beyer, the worlds first transsexual Mayor, is elected Mayor of Carterton. Her appointment makes international headlines.

Mayor Georgina Beyer

1996

At New Zealand’s first commercial wind farm, the seven stately turbines of Hau Nui are installed south-east of Martinborough, producing electricity for about 1500 houses.

1999

The annual International Balloon Festival begins in Masterton

International Balloon Festival

1999

Tranzit Group Ltd, locally owned by the Snelgrove family, is now the second-largest privately owned coach company in the country.

The 21st Century

The Wairarapa reinvents itself, towns change from rural service centres to tourist destinations, demand for lifestyle blocks and coastal development increases to accommodate weekend Wellingtonians. Commuter pressure increases on the Masterton to Wellington railway. Farmers’ markets open and new boutique producers such as olive oil, chocolate and deli produces all add to the mix. Tourist numbers and special events grow. The Martinborough Fair, Toast Martinborough and Golden Shears are now well-established popular events.

2000

Masterton-born Professor Alan MacDiarmid is a joint winner of the Nobel Prize for Chemistry.

2001

Aratoi Museum of Art and History opens on the former Wairarapa Arts Centre site. Mostly funded by Masterton Trust Lands Trust, Rigg-Zchokke Ltd erects the new building using materials largely donated by JNL Ltd.

2003

The first ‘Wings Over Wairarapa’ is held at Hood Aerodrome.

2005

Stonehenge Aotearoa opens at Ahiaruhe.

2005

Local hapu, the Department of Conservation, Ducks Unlimited and the Greater Wellington Regional Council sign a restoration agreement for the Wairio Wetland on the eastern edge of Lake Wairarapa.

2006

A new $6m hospital is opened in Masterton.

2007

The famous French ‘Cordon Bleu’ school of cuisine announces plans to open an international cooking school in Martinborough.

Early Wairarapa – The First People

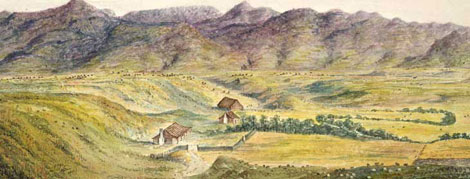

Located on the south coast of the Wairarapa is the oldest house site in New Zealand. Maori settled the Palliser Bay area in approximately 1200 AD. Archaeological data tells us it is one of the oldest inhabited areas in New Zealand.

Today evidence can still be seen of extensive tended gardens enclosed within a complex system of stone walls, showing that early Maori enjoyed a rich diet of seafood and cultivated vegetables.

Oldest House

Remains of the oldest dwelling ever found in New Zealand were excavated in Omoekau Valley, Palliser Bay. The basic design follows earlier eastern Polynesian dwellings and is still used in meeting houses today, demonstrating a striking continuity in house plan and ‘house life’ from the earliest period to the present.

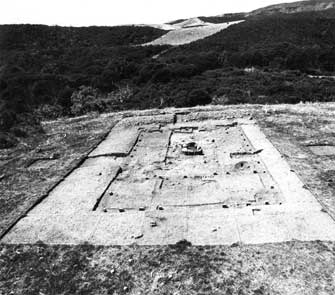

Omoekau garden and house site. The house site is shown with the black line. Stone walls are clearly evident to the left. Hoani Paraone Tunuiarangi first recorded these exact stone walls during a visit with the Scenery Preservation Commission in April 1904. Photo Kevin Jones.

The excavation of the house at Omoekau, Palliser Bay. The house measured 6.7 by 4.4 metres and was dated to approximately A.D. 1180. It was marked off by the charred butts of carefully dressed upright timbers in place along the walls and in the centre of the inner room was a stoned-lined hearth.

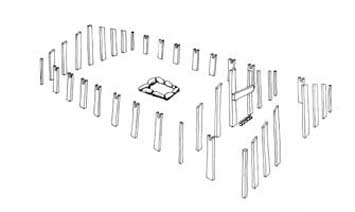

A partial reconstruction of the Omoekau house based on excavation of its site.

Pioneering Research

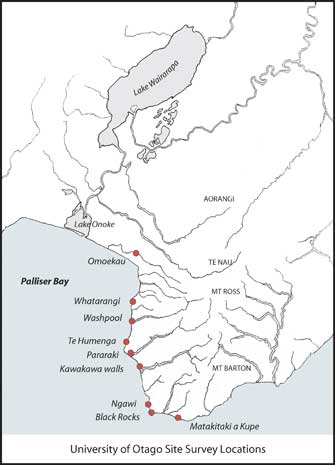

The remains of the Omoekau house were found during a pioneering regional archaeological research programme in Palliser Bay by staff and students of the University of Otago between 1969 and 1972. Led by Foss and Helen Leach the research included a site survey of some 1700 square kilometres, analysis of historic and traditional records, and excavations of 25 major archaeological sites in Palliser Bay.

University of Otago site survey locations

This huge research programme challenged existing thinking about New Zealand archaeology and laid the basis for a new understanding of early Maori life in Aotearoa. The life and culture of pre-European Maori communities had never before been described in such detail and no subsequent research programme has matched its breadth.

Extensive Gardens

Through the research, it was revealed that vast horticultural crop production was undertaken in the Palliser Bay and wider Wairarapa coastal area with an extensive series of protective stone walls, kumara storage pits, stone and soil mounds, and garden terraces near settlements.

The Washpool and Makotukutuku Stream area

These gardens of kumara and gourd dated back to the 12th Century AD. It was the first time that archaeological evidence of Maori gardening had been dated to the earliest period of settlement, showing that the first settlers had been accomplished gardeners, and not merely hunters.

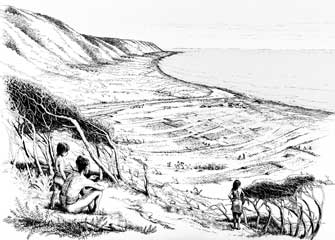

An artist’s sketch showing the gardens and village site found during the Otago University survey. Courtesy of Foss Leach and Kohunui Marae.

Population

The investigated area was home to an estimated 300 people spread amongst seven communities along eastern Palliser Bay. As with other Polynesians, the early Maori in Palliser Bay were tall; they lived a vigorous but fairly short life of approximately 40 years on average; osteoarthritis was common in adults and by 30 years their teeth were generally worn and seriously depleted due to a coarse and abrasive diet.

Coastal Resources

Using the land between the sea and the foothills for gardening, these early inhabitants also fished offshore, gathered shellfish, fished in streams and rivers and snared birds and rats in the forests. At that time forests extended almost to the sea and the riverbanks were stable and grassed. Clearance of vegetation gave rise to erosion and eventual silting of the inter-tidal areas, which resulted in a decline in the population of some shellfish species.

Stone Resources

Palliser Bay iwi made a wide variety of stone tools. The stone resources needed for making these tools were either sourced locally or were imported from a range of other places. Stone was traded and imported from as far away as the northern North Island, the west coast of the South Island and Central Otago. Over time the number of tools made from local stone increased demonstrating an increasing familiarity with the nearby geological environment and less reliance on imported raw materials.

Abandonment and Resettlement

The Palliser Bay settlements were abandoned in the early 16th century, due to the depletion of important food reserves and a decline in climatic conditions, coinciding with the ‘little ice age’, which made kumara and gourd cultivation difficult. When weather conditions improved Maori returned to Palliser Bay. Today Ngati Hinewaka, a hapu of Ngati Kahungunu, has mana whenua (guardianship) over the area.

Wairarapa:

Renowned for its Politically Astute Leaders

Following the arrival of pakeha, when faced with the complete loss of land and tribal authority in post colonial times, Wairarapa Maori leadership used only lawful means to seek redress for their grievances. Maori and Pakeha history in other parts of New Zealand has included bloodshed and loss of life on both sides. Wairarapa Maori’s astute leadership and decision making has always encouraged peace and calm in the region.

The four waka – a political accord

Ngati Kahungunu migrants arrived at Lake Onoke from Heretaunga in the sixteenth century. A political accord was struck with the Rangitane occupants. Some Rangitane, planning to leave for the South Island, were willing to cede their land in southern Wairarapa in return for the canoes in which the Ngati Kahungunu migrants had arrived.

Palliser Bay and the sand bar of the Wairarapa (Lake Onoke) Samuel Charles Brees 1810-1865 [Engraving by Henry Melville. London, 1847] Alexander Turnbull Library

The agreement and canoe exchange concluded with Te Rerewa’s parting words to his Ngati Kahungunu nephew, Te Rangitawhanga: “Live in peace with Rangitane who remain in Wairarapa. If fighting breaks out and it is Ngati Kahungunu in the wrong, then I will return, not so however if Rangitane is in the wrong”.

Intermarriage was prevalent and despite some ongoing tension the two iwi and their hapu remain and occupy Wairarapa to the present day, as envisaged by the accord created between their sixteenth century tipuna.

Nukupewapewa

Musket-bearing Maori arriving from the west coast in the 1820s had a serious impact on Wairarapa Maori. Waikato and Taranaki iwi along with other allies displaced iwi in the Whanga-nui-a-Tara and had their sights set on doing the same in Wairarapa. Attacks were resisted but most were eventually forced to retreat and seek refuge elsewhere, resulting in mass departures to Nukutaurua and Heretaunga as well as to Manawatu. Wairarapa iwi named a canoe Te Heke Rangatira (The Migration of Chiefs) to commemorate this event.

Nukupewapewa was the leading Wairarapa rangatira during these turbulent times. A party of Te Atiawa had built homes at Tauwharerata (near modern Featherston). Early one morning Nukupewapewa led an attack and succeeded in capturing several of the Te Atiawa, including prominent rangatira Te Wharepouri’s wife, Te Urumairangi, and niece, Te Kakapi.

Nukupewapewa’s release of both women, first Te Urumairangi and then Te Kakapi, was a tactical move intended to show Te Wharepouri and Te Atiawa that he wanted to make peace. Sadly, Nukupewapewa drowned when travelling between Nukutaurua and Wairarapa. The success of his strategy was apparent when in 1838 Te Wharepouri arrived at Nukutaurua and announced that he had come to negotiate peace with Nukupewapewa. His appearance took Ngati Kahungunu completely by surprise and on hearing that Nukupewapewa had drowned at sea, Te Wharepouri composed this lament:

Wairua i tahakura nou, nei, e Nuku

Kia whakaoho koe i taku nei moe

Kia tohu ake au ko to tinana tonu.

Spirit of my dreams are you, o Nuku

Come to awaken me in my sleep

That I may think it is really you again in the flesh.

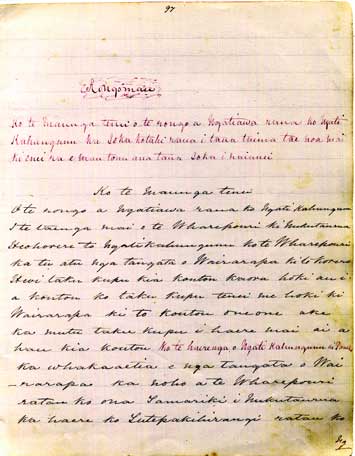

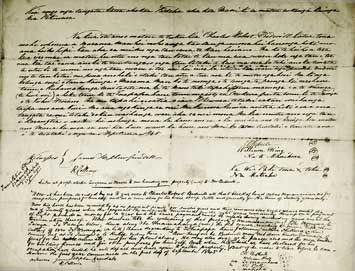

Rongomau. An account in Maori of Te Wharepouri arriving at Nukutaurua in 1838. (Written in 1888. Private Collection)

Negotiations for a peaceful return to Wairarapa were completed between Te Wharepouri and Wairarapa rangatira Tutepakihirangi. Wairarapa iwi were back in their homelands, by 1841, with west coast iwi having retreated to the west side of the Remutaka and Tararua ranges.

Thereafter Wairarapa became known as “Te Pooti Ririkore” (The District Without Hostility). This was also reportedly what Wairarapa rangatira, Ngatuere, called the Wairarapa when confronting a visiting Hauhau party at Mikimiki in 1865, later reassuring Governor Grey that “the Wairarapa will not be stained by Pakeha blood.”

Major Brown lobbies Queen Victoria and ensures the British newspapers carry the story

In 1897, Hoani Paraone Tunuiarangi accompanied Premier Richard Seddon to Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee celebration. Major Tunuiarangi was presented to Queen Victoria and received a jubilee medal and a ceremonial sword to honour the occasion. While in London, Tunuiarangi presented a petition that was adapted during a Maori Parliament sitting at Papawai in April that year.

Major Hoani Paraone Tunuiarangi – photographer Matilda M White c1890s Whangarei Museum

Papawai Marae carved figures Circa 1920s. Photo Wairarapa Archives. These carved figures (whakapakoko) surrounding Papawai marae face inwards, signifying Wairarapa’s vision for continued peace without bloodshed in the district. According to E Ramsden, Evening Post, 30 Decmber 1946, the carvers were Te Rito and others from Wairoa.

The petition called for the remaining 5 million acres of Maori land to be reserved in perpetuity. It stated that having sold some 60 million acres of land to ‘private persons and the Crown’ since 1840, Maori now desired “to retain and utilise our surviving land ourselves”. The petitioners pointed out that their request “can only be given effect to by passing such legislation prohibiting for ever the sale of our surviving lands to the Crown and private persons”, and called upon the Queen “as a memento of your anniversary to cause such legislation to be adopted”.

The petition was presented to the Secretary of State for the Colonies, Joseph Chamberlain and Tunuiarangi was asked to Parliament to explain his concerns. He also had the petition published in the London press causing considerable embarrassment to the government. Seddon was forced to agree that the sale of Maori land should cease. The effect of the petition on the Government’s thinking was evident in the preamble of a new bill which cited the 1897 petition and purported to resolve long overdue grievances.

Nireaha wins his Privy Council case

… questions of great moment affecting the status and civil rights of the aboriginal subjects of the Crown have been raised by the respondent. – Lord Davey Privy Council Decision Nireaha Tamaki v Baker, May 1901

The Wairarapa portion of the densely forested Seventy Mile Bush region stretching from southern Hawke’s Bay to central Wairarapa passed through the Native Land Court in 1871. Without a proper survey, the Court divided 187,000 acres into 11 blocks, with title mostly going to Rangitane iwi from the west coast of the North Island.

Nireaha Tamaki – Gottfried Lindauer oil on canvas c1880. Collection of the Wairarapa Cultural Trust.

Wairarapa rangatira Nireaha Tamaki rejected the inclusion of west coast iwi and claimed customary ownership of some 5,000 acres of this area, which he maintained had not been extinguished by the Native Land Court or the Crown purchase.

The New Zealand Court of Appeal rejected Nireaha’s case in May 1894. The Appeal Court said that Maori were a “primitive” tribal society and did not possess customary law which the Court needed to take into account.

Nireaha appealed to the Privy Council who, in 1901, reversed the Court of Appeal’s decision. These English “Law Lords” rejected the argument that there was no Maori customary law adding that it was “rather late in the day” for New Zealand courts to adopt such a view, given that several existing New Zealand statutes referred to Maori custom. In response, the New Zealand government circumvented the process with legislation that awarded compensation to Nireaha and limited Maori rights to scrutinize the Crown’s land-purchasing procedure through the courts.

Land Alienation Map showing extent of Maori land alienated by 1860. In Wairarapa land remaining in Maori title represents 30% of original 1840 land holding. By 1900 it was less than 10%.

The consequences of the Privy Council’s decision were significant and of lasting importance. As recently as 19 June 2003, Nireaha’s case was relied upon in the NZ Court of Appeal ruling on the Foreshore and Seabed case (Ngati Apa v Attorney General). This decision affirmed the right for the Maori Land Court to investigate Maori customary ownership of the foreshore and seabed. As had their predecessors, the government overturned the Court of Appeal’s decision by enacting through legislation, the Foreshore and Seabed Act 2004.

Nireaha appealed to the Privy Council who, in 1901, reversed the Court of Appeal’s decision. These English “Law Lords” rejected the argument that there was no Maori customary law adding that it was “rather late in the day” for New Zealand courts to adopt such a view, given that several existing New Zealand statutes referred to Maori custom. In response, the New Zealand government circumvented the process with legislation that awarded compensation to Nireaha and limited Maori rights to scrutinize the Crown’s land-purchasing procedure through the courts. The consequences of the Privy Council’s decision were significant and of lasting importance. As recently as 19 June 2003, Nireaha’s case was relied upon in the NZ Court of Appeal ruling on the Foreshore and Seabed case (Ngati Apa v Attorney General). This decision affirmed the right for the Maori Land Court to investigate Maori customary ownership of the foreshore and seabed. As had their predecessors, the government overturned the Court of Appeal’s decision by enacting through legislation, the Foreshore and Seabed Act 2004.

He Tipuna Onamata –

Ancient Ancestors

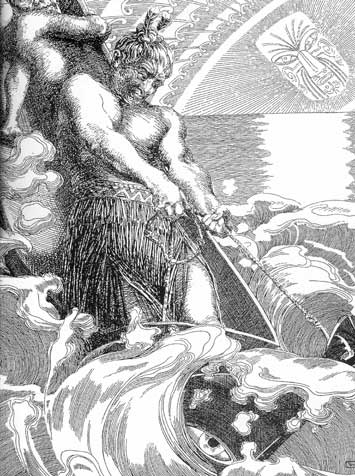

MAUI – TIKITIKI-A- TARANGA

Maui-tikitiki-a-Taranga, the youngest son of Taranga and Irawhaki, has been described by many as being bold, mischievous, and defiant. He was always pushing the boundaries that separated the natural and the supernatural.

Te Ika a Maui

Expert Fisherman

Maui’s older brothers were great fishermen. On one occasion the brothers were preparing for a fishing expedition and Maui wanted to join them. They argued amongst themselves before finally agreeing to let Maui go along.

During the expedition, Maui insisted that they go further out to sea than usual so that they could catch larger fish. Reluctantly his brothers and their companions agreed. Once they reached the place where Maui wanted to fish, he took out his matau (fish-hook) fashioned from the jawbone of his grandmother, Muri-ranga-whenua.

Te Ika a Maui – The Fish of Maui

Maui drew blood from his nose which he used as bait. Casting his hook into the ocean, it wasn’t long before he caught a fish. After a great effort he pulled up Te Ika a Maui, the fish of Maui, the North Island of New Zealand.

If we look at the outline of the island it is easy to imagine the shape of this great fish is believed to have been a giant sting-ray. The parts of the island that reflect particular features of the fish are personified in tribal histories throughout Aotearoa. Te Hiku o te Ika, the tail of the fish is Muriwhenua and the head, Te Upoko o te Ika, Wairarapa and Wellington. Te Waiponamu, the South Island of New Zealand is referred to as Te Waka a Maui, the canoe of Maui.

Wairarapa Landmarks

Wairarapa Moana, Lake Wairarapa is the eye of the fish, Te Karu o te Ika. Other areas are Turakirae, the nostril, or forehead of the fish; Ngawi, the jaw bone of the fish; and the mountain ranges Remutaka, Tararua and Ruahine, the spine or Maui’s fishing line.

KUPE

Hawaikinui

Kupe, a great Polynesian navigator, was the first to discover Aotearoa. Kupe and his people travelled to these shores from Hawaiki aboard Matahourua in pursuit of Te Wheke a Muturangi, the pet octopus of the chief Muturangi. The octopus, which Kupe eventually killed at Arapaoa, was playing havoc with the fisheries in Hawaiki by using other octopi to take the bait from the fishing lines.

Kupe’s Sail Rock (Nga ra a Kupe) Palliser Bay. William Mein Smith (1799-1869) between 1849 and 1855?

Naming the Land

Kupe made several landfalls along the rugged Wairarapa coast. Some of these include: Rangiwhakaoma (Castle Point) where the octopus hid in a cave (Te Ana o Te Wheke a Muturangi) to give birth; Pahaoa where Kupe left his nephew Rerewhakaaitu (the name of a river east of Martinborough); Tuhirangi where he left another nephew Mataoperu (the name of a stream on the coast below Tuhirangi Maunga); and finally Te Matakitaki-a-Kupe and Te Kawakawa.

Te Matakitaki a Kupe

Problems with their waka may have been the cause of a prolonged stay at Matakitaki. In one account Kupe, grieving the loss of his daughter, climbed to the top of a high ridge and gazed at the horizon in the direction she had travelled. This place became known as Te Matakitakinga a Kupe ki te paenuku te waahi i haere ai tona tamahine. The rocks were imprinted with “nga toto me nga roimata me te wai o te ihu” (the blood, tears and mucus) of Kupe in a moment of grief. In another version, Kupe was gazing at the multitudes of fish and looked up to see land on the horizon.

Te Kuri o Kupe

Kupe also brought with him a kuri, a dog, who wandered the coastal and inland areas of the Wairarapa and finally settled at Hurunui-o-rangi. The kuri remained as a kaitiaki or guardian of the area.

Kupe and Ngake compete

While camped at Te Matakitaki a Kupe, Kupe and his companion Ngake competed which of them could make a sail in the shortest time. Kupe completed his during the night whilst Ngake did not complete his until dawn. Both sails, Nga Ra a Kupe, are still visible today as a rock formation hanging from the cliffs. Further inland Kupe and Ngake competed again, this time to build a waka. Kupe completed his waka, Ngake did not and these complete and incomplete canoes, Nga Waka a Kupe, remain with us as the hills to the east of Martinborough.

Te Kawakawa

The area adjacent to Te Matakitaki is Te Kawakawa, the name of a stream near the current township of Ngawi, where Kupe’s daughter made a wreath from Kawakawa leaves.

The waka Hawaiki-nui, built by Matahi Whakataka Brightwell of Wairarapa. In 1985, Matahi sailed this traditional twin hulled (waka hourua) canoe from Tahiti to Aotearoa. Using traditional navigational techniques first acquired from Kupe, it took Hawaiki-nui 23 days to reach Auckland from Rarotonga.

HAUNUI A NANAIA

Haunui-a-Nanaia, also known to some as Haupipi and Haunui-a-Popoto, a direct descendant of Kupe and his wife Aparangi. Tunuiarangi, a Wairarapa scholar, traces his whakapapa as follows:

Ko Kupe i a Aparangi

ka puta (who begat) ko Haunuiaparangi

Ko Popoto i a Nanaia

ka puta ko Haunui-a-Nanaia

Ko Haunui-a-Nanaia i a Rakahanga

ka puta ko Uehangaia

Haunui’s father Popoto arrived in Aotearoa on the Kurahaupo waka. Their waka had set off from Hawaiki to find Toi te Huatahi, the grandfather of Whatonga. Whatonga was the principal chief on Kurahaupo. He settled in Hawkes Bay and travelled south to Rangiwhakaoma (Castlepoint) where he established a pa named Matirie.

The Arrival of the Maoris in New Zealand, Goldie and Steele 1898. This painting portrays late 19th century attitudes towards Maori as a dying race and disdain for Maori and Polynesian voyaging skills.

In pursuit of Wairaka

Haunui lived at Te Matau-a-Maui, Hawkes Bay. Upon returning home from an expedition he discovered that his wife, Wairaka, had been abducted by slaves, Kiwi and Weka. He travelled in pursuit down the west coast of the North Island naming areas of land, rivers and streams as he went. After exacting his revenge on Kiwi and Weka, Haunui set about returning home. Motuwairaka is the name given to the area where he left Wairaka and who remains immortalised in stone, partly pounamu.

Haunui returns home

It is Haunui’s return home to Te Matau-a-Maui that has the greatest significance to the people and the land of the Wairarapa. His return began at the summit of the Tararua ranges, at Remu-taka, where he sat and rested.

Wairarapa Moana – Lake Wairarapa

Haunui was responsible for naming Wairarapa Moana (Lake Wairarapa). There are two common interpretations of this name; both refer to the state of Haunui’s eyes. Firstly, rarapa can mean glance, which describes Haunui’s actions as he stood and glanced over the land. Secondly, rarapa can also mean to flash, glisten and reflect which is how Haunui’s eyes reacted to seeing the water below.

Hence he named the lake, Wai (water) rarapa (glistening eyes).

Naming the rivers

Wairarapa Maori also attribute the naming of some rivers in the region to Haunui, rivers such as: Tau-whare-nikau also known as Tau-here-nikau, where he came across a dwelling thatched with Nikau; Waiohine, named for his wife Wairaka; Waiawangawanga, ‘the waters of uncertainty’, where he hesitated (now referred to as Waingawa); Waipoua, where he tested the depth of the water with his taiaha, and Rua-mahanga meaning ‘twin forks’ where he looked around for a crossing and found a waka-inu-wai (a bird’s drinking trough) placed between two forked branches.

Wairarapa Tangata Whenua

Iwi

Iwi (tribe) is the largest social grouping in Maori society. Each iwi is made up of several hapu (sub-tribes), both large and small, whose members share a common tipuna (ancestor). Hapu consist of whanau (families) occupying one or a number of papakainga (settlements).

Wairarapa has two main iwi, Rangitane and Ngati Kahungunu. Some early iwi in Wairarapa were Te Tini o Awa, Te Tini o Orutu, Ngati Mamoe and Waitaha. Little is known about their presence in the region, some moved south to Te Waipounamu, the South Island, and others merged to form new iwi.

Rangitane O Wairarapa

Rangitane, otherwise known as Tanenuiarangi, was the grandson of Whatonga who came to Aotearoa on the Kurahaupo waka (voyaging canoe). He is the ancestor of an iwi that once dominated a large portion of the lower north island. Today Rangitane occupy four main areas: Manawatu, Tararua, Wairau and Wairarapa regions. The descendants of Whatonga, Rangitane and his uncle Taraika, who took the tribal name of Ngai Tara, have continuously occupied the Wairarapa region since the 14th century.

Wairarapa Archive

Ngati Hamua

There are many hapu associated with Rangitane o Wairarapa and Ngati Kahungunu ki Wairarapa.

Ngati Hamua is the paramount hapu of the Rangitane o Wairarapa iwi. The hapu gets its name from a man called Hamua who lived during the 15th and 16th centuries. He was the great-great-grandson of Rangitane.

Ngati Hamua is considered a matua hapu or one that has its own network of sub hapu. Ngati Hamua was sometimes called an iwi, indicating its size as a hapu. Throughout its long history, Ngati Hamua has maintained a constant presence within the Wairarapa. Today, as in the past, the people of Ngati Hamua retain a quiet yet influential position within local communities.

Ngati Hamua Environmental Education Sheets – produced by Rangitane o Wairarapa and Greater Wellington Regional Council 2005.

Ngati Kahungunu Ki Wairarapa

Kahungunu was the great grandson of Tamatea, rangatira of the ancestral Takitimu waka. Known as a lover and provider more than a fighter, Kahungunu had eight wives. His most famous spouse was Rongomaiwahine, a descendant of Popoto, who lived on the Mahia peninsula in the Hawkes Bay. It is through the uri mokopuna (descendants) of Kahungunu and Rongomaiwahine that the Ngati Kahungunu iwi came into being. It is the dominant iwi along the east coast from Wairoa to the Wairarapa. Several of their immediate descendants are famous for their prowess in battle and ability to create alliances through marriage.

Hapu boundaries and resources

In the Wairarapa Ngati Hamua was most prominent in the upper part of the main valley. Their area stretched from the eastern hills to the top of the Tararua Mountains, and from the Waingawa River north to Woodville.

Te Tapere nui o Whatonga (The Great Domain of Whatonga) was thickly covered in forest, later called the Seventy Mile Bush, that stretched north of Masterton to Dannevirke and had several Ngati Hamua papakainga. The giant forest contained a rich supply of resources from which the hapu could collect berries, hunt birds and catch kiore (native rat). In the summer they moved out to coastal papakainga to harvest kaimoana (sea food) and garden vegetables such as kumara.

Te Tapere nui o Whatonga was lost to Ngati Hamua under very litigious circumstances. In the 1890s Nireaha Tamaki, a Ngati Hamua rangatira, led a case against the Crown, which he took to the Privy Council in London and won. However, this did not result in the return of the land to Ngati Hamua. Recently, the Crown’s dealings in this matter have come under renewed scrutiny through the Treaty of Waitangi Tribunal process.

Outside of the main valley, Ngati Hamua also had pa (fortified village) and papakainga throughout the Wairarapa region.

A Selection of Key Events

Ahi Kaa Keepers of the flame

During the 1830s, small groups of Ngati Hamua maintained a presence in the Wairarapa while most of their people lived in exile further north due to the invasion of the region by outside aggressors. When the return home began in the early 1840s Ngati Hamua greeted the returning exiles at Te Kopi in Palliser Bay and handed back land to the Te Hika o Papauma hapu at Mataikona.

Masterton is founded

The establishment of Masterton, the economic centre of the Wairarapa, was in large part due to the goodwill of Ngati Hamua. Negotiations were concluded in 1853 by the rangatira, Retimana Te Korou and son-in-law Ihaia Whakamairu, on behalf of the Hamua people.

Library Square, Queen Street, Masterton

Nga Tau E Waru is built

The wharenui Nga Tau E Waru (The eight years) at Te Ore Ore marae east of Masterton was built between 1878 -79. Paora Potangaroa, of Te Hika o Papauma, built Nga Tau E Waru on behalf of his Ngati Hamua relations. The house was one of the biggest of its time at 96 feet long and 30 feet wide It was also significant because of the unique patterns used in its carvings.

Nga Tau E Waru, Te Ore Ore Marae c1880s

National Library of Australia

The Committee of Hinerangi

During the early 1900s, The Committee of Hinerangi set moral standards by which Ngati Hamua were required to live. The intention of the committee of elders was to keep European authorities out of the lives of their people. After initiating their own laws traditional family heads presided instead of police and judges.

Ngati Hamua today

A concentrated population of Ngati Hamua have always lived within traditional boundaries in the Masterton area, allowing touchstones of identity such as ancestral landmarks, Te Ore Ore marae and family lands to be part of everyday life.

Unusually, Ngati Hamua does not have a legal entity to represent its people. This has given the hapu a lower profile in the public eye. However several of its traditional institutions and practices continue to be maintained. Growing up knowing kaumatua (elders) such as the late Kuki Rimene, his brother James Rimene (M.N.Z.M.) and Pani Himona (JP) has meant that Hamua people continue to turn to proven hereditary leaders for direction and guidance.

Takitimu Whare Whakairo

A Sacred Carved Meeting House

… they have been occupied for six years in their execution of most elaborate carvings… the house would eclipse any other in the colony… much money has been wasted over this house. – Maunsell, Assistant to Resident Magistrate, Native Land Court, 1886

Interior of Meeting House

M C (Kitty) Martin photograph album

Takitimu wharenui was a very large and elaborately styled meeting house. It measured 70 feet in length and was 20 feet wide. Expert carvers, including Hori Paihia, a Ngati Porou master carver from Poverty Bay, were employed for 8 years in its construction. They first worked at Papawai where several years were spent preparing the carvings. The milled timbers and carvings, including a 70 foot ridge pole, were floated on a barge to the marae site at Kehemane (Gethsemane), near Martinborough, where at long last the construction could be completed.

Front of Meeting House.

Martin Family papers. Waitawa

Opening Takitimu in 1891

Tensions arose over the decision to locate the house at Kehemane. Tamahau Mahupuku wanted Takitimu to remain at Papawai which he was planning as a centre of Maori political activity, but he deferred to the wishes of Hikawera who wanted the house erected at Kehemane. The division was apparently resolved sufficiently to allow the opening to proceed.

Te Kooti came to open Takitimu on the 1st of January 1891. There is an oral tradition that it had been previously opened by Te Kooti in 1887. During the opening, Te Kooti quoted a Ngati Awa pepeha, “Kai waho te mirimiri. Kai roto te rahurahu.” The literal translation is “beware of soothing flattery on the outside, for on the inside there is a roughness or a hidden purpose.” This is a reference to the troubles over the location and purpose of the house. However, Te Kooti reassured the gathering that the fault had been on his side and that the coming year would be a gentle one.

Poupou recovered

The poupou (carved ancestral post) on display (to the right) was discovered partly buried in 1950 by Norman Martin while he was ploughing alongside the Ruamahanga River, near Martinborough. Mr Martin immediately recognised its importance and took it home. He then made enquiries about the poupou with an elder from the Papawai Marae who told him that two poupou prepared to an unfinished state, like this one, had gone missing in flood waters near Papawai. They were being prepared for transportation elsewhere. The poupou was kept in the Martin’s shearing shed until recently when it was ceremonially placed into the care of Aratoi Museum of Art & History.

The carving has been prepared to this “unfinished state” with a metal adze. The similarities between the unfinished poupou and completed poupou in the interior of the Takitimu wharenui are more evident in the style of preparation than the actual finished carving. The length and proportions are noticeably different (from the photos). Its preparation has a strong Ngati Porou influence. The notched chiselled pattern visible at the base of the carving, known as pakati, is a commonly used pattern and is a dominant feature in the carvings of the Takitimu meeting house.

Takitimu and the Ringatu faith

The style and decoration of Takitimu is directly linked to Rongowhakata military leader and prophet, Te Kooti Arikirangi Te Turuki and his Ringatu (Raised hand) faith. This faith was founded by Te Kooti in 1868 while he was imprisoned on the Chatham Islands. The Ringatu faith flourished in parts of Wairarapa during the 1870s as Maori were suffering the negative impacts of losing their land. The arrival of the carvers in 1880 was noted in the local press, although their links with Te Kooti went unnoticed. Local officials would surely have objected had they known followers of Te Kooti were resident in the district.

The interior poupou along the walls of Takitimu are a classical Ngati Porou style. The patterns on the front, in particular, are identical to other meeting houses built for the Ringatu faith. The carving and painting on the front amo (side posts) and maihi (barge boards) are in the style associated with Te Kooti. Inside the mahau (porch) are the same painted marakihau figures that appear on the meeting house Te Tokanganui-a-noho at Te Kuiti.

Exterior gathering Dec 1907

The loss of a gift

Tamahau gifted Takitimu to the nation in 1901. His message to Native Minister Sir James Carroll was that: “the Ngati Hikawera and the Ngati Moe have come to a unanimous decision… to present the carved house Takitimu now standing at Kehemane wholly as it stands to you and the Government as a token of appreciation of your efforts in connection with the preservation of the handiwork of your Maori people.” Tamahau was referring to the antiquities legislation the government was proposing to prevent taonga (treasures) from being removed overseas. This was, he added, “a chief’s gift” on behalf of the hapu living within the Rongokako boundaries.

However, this was not the end of the tension surrounding Takitimu. Tamahau died in January 1904 and was taken to Takitimu for his tangi. He was buried in the Kehemane urupa (cemetery). It was later claimed that he wanted to have Takitimu removed to Papawai but this was never to happen. Takitimu remained at Kehemane and continued to be used by its people as a meeting house. Sadly, it was destroyed by fire on the last night of 1911, just hours before the 21st anniversary of the opening.

Interior. Poutokomanawa (central carved post) foreground

Lindauer portraits of South Wairarapa Rangatira are at the rear of the meeting house

M C (Kitty) Martin photograph album

Scholarly People

THE Wairarapa Whare Wananga

One of the earliest and most important recorded Maori histories comes from the renowned Wairarapa whare wananga (house of higher learning). This oral history was taught by important Tohunga (learned experts). Te Matorohanga was one such tohunga who gave permission for Hoani Te Whatahoro Jury to record his teachings so that the knowledge would be stored for future generations.

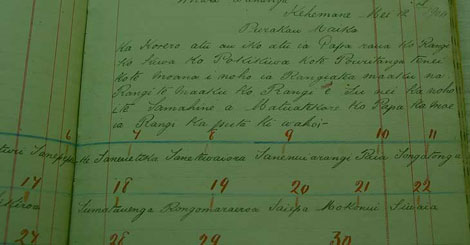

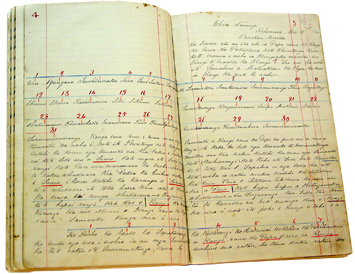

Komiti Tupai manuscript. The writing of Purakau Maika at Kehemane (Takitimu meeting house) on 12 May 1904.

The traditional Wairarapa whare wananga was a tapu (sacred) institution of higher learning, something akin to a university, where tikanga (protocols) were strictly enforced by the tribe, scholars and teachers alike. Although colonization disparaged traditional cultural knowledge, Wairarapa Maori sought to use their learning institutions to mitigate the impact of land loss and diminishing tribal autonomy. Preservation and protection of tribal lore became an added function of the whare wananga.

However, the new culture was rampant and many Tohunga saw their knowledge being disrespected. This knowledge, which was complex, valuable and only made available to a select few, became lost on their death. The Wairarapa whare wananga was the last of the many that were dotted throughout the country.

Tupai Whakarongo Wananga

The earliest account of a whare wananga in the Wairarapa relates to Tupai, a tohunga who came from Hawaiki on the Takitimu waka (canoe). On the journey south in search of pounamu (greenstone), Tupai got off the waka along the Wairarapa coast where he established a whare wananga. Rongokako, Kahungunu’s grandfather, attended the wananga and was considered a failure by Tupai but he was allowed to perform a final test. This involved reciting a karakia correctly, taking gigantic strides to an offshore island and returning with the particular rimurapa (seaweed) of that island. Rongokako was the only student to complete the test correctly thus ensuring his graduation. His giant strides also carried Rongokako to the woman of his choice, Muriwhenua, ahead of Paoa who was also seeking her affections.

In 1902, Niniwaiterangi Heremaia and Tamahau Mahupuku established a committee called Te Komiti o Tupai in honour of their ancestor and his whare wananga in the Wairarapa. The wharenui (meeting house) on the Martinborough marae is also named after Tupai.

Te Matorohanga

In the late 1850s at the end of a large political gathering (possibly at Waihenga near modern Martinborough) a request was made of the learned men present to explain the origins of Maori in Aotearoa. Te Matorohanga was chosen to lecture and two other tohunga, Nepia Pohuhu and Paratene Te Okawhare agreed to assist. So began the archiving of a unique body of knowledge that was later to become a source of research and information for all Maori.

Nga Kete Wananga, Cliff Whiting, 1989. Carving Christchurch High Court

Te Matorohanga was born around the turn of the nineteenth century. In his youth he trained at whare wananga in Wairarapa and Wairoa. About 1836, during the period Wairarapa iwi were driven out of their homes by west coast iwi, he studied at the famous whare wananga of Te Rawheoro at Uawa (Tolaga Bay).

Knowledge was brought back to earth by Tane in three kete from the twelfth and highest domain – Te Toi-o-nga-Rangi. The three kete, Te Kete Tuauri, Te Kete Tuatea, and Te Kete Aronui contained the celestial (Te Kauae Runga) and the earthly (Te Kauae Raro) knowledge which provided the basis for the teaching within the whare wananga. Te Matorohanga’s lectures included very detailed accounts of creation, discovery and settlement of Aotearoa, genealogies of ancestors, and incidents from tribal histories. His stories about Kupe and Maui are retold in this exhibition.

Hoani Te Whatahoro Jury

Hoani Te Whatahoro Jury was chosen to be the scribe for the lectures of Te Matorohanga, Pohuhu and Te Okawhare. Te Whatahoro was taught to read and write by his father and further educated at mission schools paid for by Governor George Grey. He was a prolific writer on Maori traditions and customs and continued to record information from the teachings of Nepia Pohuhu and Te Matorohanga until their deaths in the 1880s.

Hoani Te Whatahoro Jury. Attributed to Joseph Gaut. Oil on canvas. Late 1800s.

Collection of the Wairarapa Cultural Trust.

Te Whatahoro was a member of the Tupai and Tanenuiarangi Komiti. These committees were conceived in 1899 at Papawai by Tamahau Mahupuku and Niniwaiterangi Heremaia. They were made up of learned Wairarapa men and women who took on the task of collating all of the books containing ancient knowledge. The committees met from 1905 to 1910 to consider the information gathered and once the information contained in a manuscript was approved, it was stamped with a seal. In this way Wairarapa rangatira authenticated their ancient knowledge for public use. For the very first time, Te Whatahoro produced the writings of the Te Matorohanga whare wananga having previously been instructed by the tohunga to keep them secret. The manuscripts were passed over to the Dominion Museum for safekeeping.

Seal of Te Komiti Tupai

Lore of the Whare Wananga

Percy Smith, one of the founders of the Polynesian Society in 1892, published the Journal of the Polynesian Society. The society was formed largely in response to the widespread belief that Maori were a dying race. Its members hoped to preserve, interpret and speculate about the traditional knowledge of the Maori before the race disappeared completely. In 1913, Smith translated and published the teachings of the three great Wairarapa tohunga as recorded by Te Whatahoro almost 50 years earlier, under the title ‘The Lore of the Whare Wananga’.

The Lore of the Whare Wananga has been drawn on heavily as a source of traditional Maori knowledge by many academics. Today, the foresight of the local ancestors together with Te Whatahoro’s transcripts has made available a valuable knowledge base for all Maori.

Mana Motuhake

Promises by the Crown

The Treaty of Waitangi was signed at Waitangi (Bay of Islands) on 6th February 1840. The Treaty guaranteed Maori total control over all their lands and taonga with the Crown having the pre-emptive right of purchase of the land. Wairarapa rangatira Tutepakihirangi signed a copy at Turanga (Gisborne) in May.

Now then send some white people to feed sheep, should white people come, I myself will arrange the payment for the use of my land – Wereta Te Kawekairangi to Eyre Lieutenant – Governor of New Munster 23 January 1849

A Thriving Economy

Maori responded positively to the desire of Pakeha to farm in Wairarapa. Between 1845 and 1850, a flourishing trading economy developed with Maori leasing approximately 100,000 acres to the settlers for which they were receiving an estimated £1200.

Samuel Brees, 1810–1865. Maori Pa, Palliser Bay and Cape c1844. Alexander Turnbull Library.

Ample reserves shall be retained for you if you will sell your lands; but if you will not conclude such an arrangement, then I shall desire the Europeans to depart from your land, and shall put an end to the arrangements at present existing between you and them.- Governor Grey to Wairarapa Maori 20 March 1847

The Crown claimed that leasing was contrary to the Crown’s pre-emptive right under the Treaty of Waitangi. In return for selling their land cheaply, Grey promised health, educational and economic benefits. Settlers, for their co-operation, would secure title to their leasehold runs. Joseph Masters’ efforts early in 1853 to establish a town near the home of Retimana Te Korou at Ngaumutawa with the promise of commercial opportunities helped set the stage for Grey’s final act.

I therefore thought it my duty, before quitting this part of New Zealand, to visit the Wairarapa district, and … seeing this question settled… Grey to Colonial Secretary Newcastle, 27 September 1853

Komiti Nui

In August 1853 Grey convened a large gathering of Wairarapa rangatira (chiefs), dubbed “Komiti-nui” (large committee). The meeting was held at Turanganui, near Pirinoa, and was commemorated with the planting of trees. Grey’s performance at Komiti-nui must have been convincing as, within six months, the government’s land purchaser Donald McLean laid claim to over one and a half million acres.

The Natives appear to be very much depressed in spirit in the valley and more than half starved. I have no authority but have been compelled to give them some food, could not some employment be found for some of them. William Searancke to McLean after a large meeting at Waihenga (near Martinborough) in September 1859

Grey’s promises of benefits were included in sale deeds but very few of the promises were kept and Wairarapa Maori quickly became impoverished with the Crown’s thirst for cheap land far outweighing any protective obligations under the Treaty.

The Papawai Parliament

Maori Align themselves with the Biggest Superpower of the Time.

Papawai, originally called Te Manihera Town after the prominent rangatira of the area, was established as part of Grey’s inducements for agreeing to the land transactions of 1853. Tamahau Mahupuku became very influential at Papawai after the death of Te Manihera in 1835. He and his older brother Hikawera ran a very successful farm and used their wealth to develop Papawai as a centre for Wairarapa Maori’s social, cultural and political aspirations.

Under Tamahau’s leadership a substantial building programme took place . The Takitimu Wharenui, built at Kehemane, near Martinborough, was an outstanding architectural achievement. So too was the Aotea-Te Waipounamu complex, famed as a venue for the Papawai Maori Parliament. It opened on 14 April 1897, the day Parliament came to Papawai for its sixth sitting. Premier Richard Seddon was present as well as several Pakeha and over a thousand Maori.

Tamahau Mahupuku leading the Hikurangi Brass Band, circa 1890s. Wairarapa Archives

Te Kotahitanga O Te Iwi Maori

Hoani Paraone Tunuiarangi represented Wairarapa at Waitangi, Bay of Islands, on 14 April 1892. Here, Maori resolved to establish a national union, Te Kotahitanga o Iwi Maori (The United Maori Tribes), and Te Paremata Maori (The Maori Parliament), and to engage formally with the ‘Pakeha Parliament’ and give effect to the Treaty of Waitangi. From 1892 until its demise in 1902, the Maori parliament sat in different parts of the country. Sittings were major events with frequently over 1,000 Maori (men, women and children) present. Wairarapa rangatira played a prominent role in the Maori parliament.

Tamahau hosted sessions of the Maori parliament at Papawai marae regularly from 1897.

Nga Take Nunui. The list of resolutions passed at Papawai’s Maori Parliament on 14 April 1897.

Wairarapa Moana

The lake was not bought for £2000. It was given to the Government, and was accepted in that spirit, and in that spirit shall ever be dealt with. Seddon 18 January 1896, Pigeon Bush