Paora Te Potangaroa was the son of Ngaehe, of Ngati Kerei and Ngati Te Whatu-i-apiti, and Wiremu Te Potangaroa, a leader in the Mataikona area of Wairarapa, of Te Ika-a-Papauma, a hapu of Ngati Kahungunu. Through his father’s mother, Nau, Paora was related to the Hamua people, a section of Rangitane.

In 1853 Paora signed the deed of sale of the Castlepoint block, a huge area stretching from the Whareama River inland to the Puketoi range, and north to the Mataikona River. It was the first major purchase made by the chief land purchase commissioner, Donald McLean, in Wairarapa. Paora later signed away the Tautane block, in the Porangahau area, and the Waihora block, but of all the Wairarapa chiefs he was to be the most resistant to the lure of land-selling.

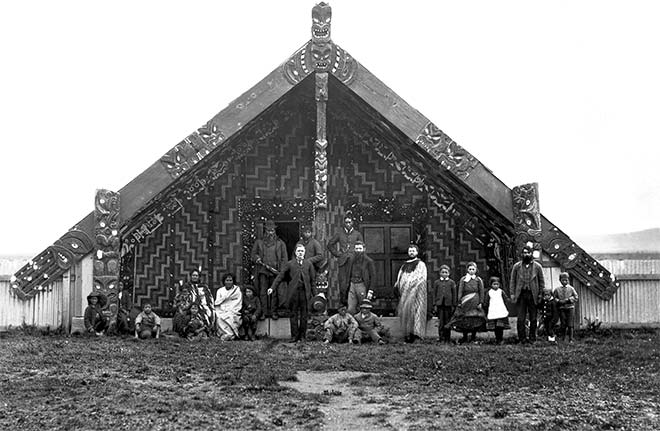

Paora’s position as a prophet and leader in Wairarapa was recognised from the early 1860s; he was asked to accept nomination as Maori King but refused. In 1878 he inspired the many hapu of the upper Wairarapa valley to build a large carved house at Te Kaitekateka, later called Te Ore Ore, near Masterton. This area was under the mana of Wi Waaka, a staunch supporter of the runanga movement and the King movement, and a protector of the emissaries of Pai Marire. During construction animosity developed between Paora and Te Kere, a master carver and prophet from Wanganui. Te Kere and Wi Waaka began to resent Paora’s growing influence, which tended to undermine their positions. Te Kere was particularly incensed at the size of the planned house, 96 by 30 feet. Having prophesied that it would take eight years to finish the house, he departed to build a rival house for Ngati Rangiwhaka-aewa at Tahoraiti.

In spite of Te Kere’s prediction, the house was finished by 1881. Paora bestowed on it, in derision of Te Kere’s powers as a prophet, the name Nga Tau e Waru (The Eight Years). The house incorporated many unusual features. The carvers Tamati Aorere of Ngati Kahungunu and Taepa of Te Arawa made use of unique double ‘S’ patterns, swastika-like motifs, and unusual rafter and panel paintings. Inside the house Paora had erected a stone believed to be a medium of communication with the world of gods and spirits. In addition, at Paora’s behest, Te Kere had carved into the ridgepole above the door, in a position where it could not easily be seen, a representation of male and female genitalia in the act of coitus. The intention was to remove the tapu of chiefs entering the door beneath it. When Wi Waaka entered the house he collapsed, semi-paralysed, and had to be helped outside. With hindsight, this collapse was attributed to the effect of the carving, designed to protect the tapu of Paora himself.

When the house was being carved Paora was at the height of his influence and popularity. He was preaching Christianity expressed in Maori concepts and when he appeared in public, people gathered round him for instruction; between these appearances he spent much time in meditation. Associated with the completion of Nga Tau e Waru were a number of his prophecies which predicted that a new and great power was to come to the people from the direction of the rising sun. Various interpretations were made: it was believed to herald the arrival of the gospel of Jesus Christ, as interpreted by the Mormons; and it was believed that missionaries would come from the east and set in place a new church. In 1928, when the religious leader T. W. Ratana visited Te Ore Ore at the request of the people, he removed the stone set up by Paora inside Nga Tau e Waru, repositioning it outside. The move silenced the medium. The coming of the Ratana faith is now widely believed to be the fulfilment of Paora’s prophecy.

In 1881 Paora announced that he had experienced a prophetic dream; he called his people together to interpret his vision. His mana was so great that the crowd at Te Ore Ore in March 1881 was variously estimated at between 1,000 and 3,000. Huge preparations had been made for their arrival, including the preparation of a great feast – a pyramid of food 150 feet long, 10 feet wide and 4 feet high. Many Pakeha visitors attended the gathering, some out of curiosity and scepticism. On 16 March 1881 the gathering awaited Paora’s prophetic utterance. About 1 p.m. he emerged from Wi Waaka’s house and presented his revelation in the form of a flag divided into sections, each bordered in black. Within each section were stars and other mystical symbols. It was raised to half-mast on the flagpole in front of the meeting house. Paora unsuccessfully asked his people to interpret its message. In spite of the scepticism and anger of those anxious for an immediate miracle, he refused to explain his meaning. The next day he appeared again and told the crowd: ‘Look at the flag. Tell me what it means.’ He made no further explanations. The gathering ended in disorder and heavy drinking.

Several weeks later Paora emerged from seclusion to make a declaration to his followers: in future they should neither sell nor lease land, should incur no further debts and refuse to honour debts already incurred. The meaning of at least part of his flag now became apparent. The black-bordered sections of the flag represented the huge blocks of land already alienated. The stars and other symbols represented the inadequate and scattered reserves, the sole remainder of a once great patrimony. Paora had been moved to prophecy by the failure of his people to understand the process by which they were dispossessing themselves.

Three months later Paora Te Potangaroa died. Pakeha authorities greeted his death with relief; they had feared the ‘fanaticism’ his movement had caused. The tangi was held at Te Ore Ore and the body carried by hearse to the settlement at Mataikona. As Paora lay dying, he had presented his son Kingi with a box of silver, the money taken at the Te Ore Ore gathering in fines for drinking. This treasure paid for his funeral.