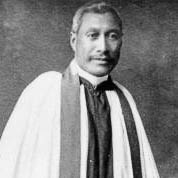

Haimona Patete, about 1900

Although little is known of Haimona’s childhood and education, he was literate in both Maori and English, which suggests schooling of some sort, perhaps with local missionaries or at a native school. It is probable that he spent his early life on D’Urville Island. When the island was apportioned between its owners by the Native Land Court in 1895, he received 1,205 acres, which he leased out until selling it to the Moleta brothers in 1911. He retained interests in outlying islands and surrounding lands. In 1894 Patete had been instrumental in persuading the government to address Ngati Koata’s grievance over their loss of Takapourewa (Stephens Island); this had been acquired compulsorily for a lighthouse in 1891. The Native Land Court awarded £140 compensation in 1895.

In the 1890s Patete moved to the Ngati Kuia pa at Ruapaka, outside Canvastown (near Havelock), and often travelled through Marlborough and Wairarapa. He probably had three wives. His first wife, Harena, a tohunga, died childless. In 1898 he married Pirihira Pitama (Noti Pitama), of Ngati Kuia, Rangitane and Te Ati Awa descent. Haimona’s influence in, and close contact with, Wairarapa from the late 1890s may have stemmed from Pirihira Pitama’s sister’s connection to the area. Patete seems to have taken a third, customary, wife, Ani Rarua, for a time, from 1901.

Haimona Patete began to emerge as a religious and political leader in the 1890s. Following a vision he had during an illness, he established Te Hahi o te Ruri Tuawhitu o Ihowa (also called the the Church of the Seven Rules of Jehovah), which incorporated the teachings of the prophet Paora Te Potangaroa. His church was one of the first to emerge in a period of new Maori responses to Christianity. European beliefs were no longer to be rejected, but the church would nevertheless minister to the special needs of Maori. The leader was seen as an evangelist rather than as a traditional tohunga, yet still retained a distinct Maori character. Patete appeared to possess healing powers and was said to have cured a young girl, Rere Hori Tekuru, who could not be saved by two doctors. He revived her by means of a prayer and a command to arise and walk.

The church’s hierarchical structure, teachings and services all reflected the Church of England, although the Holy Communion was omitted: the eating of Christ’s body was seen as abhorrent by many Maori because it symbolised contempt for a person’s body and thus destroyed their mana. Adherents were exhorted to repent, have faith in God through Christ and live according to the commands of Scripture. The British sovereign, as ruler of New Zealand and head of the Church of England, was also to be the sovereign of Maori and head of their religion.

The church spread in the mid 1890s to Wairarapa, where it gained many adherents under Taiawhio Te Tau. In 1903 it was reported to have found support from the Ngati Tahinga leader Tainui. Many Maori of other religions took exception to its claim to be the one true church for the Maori people, and Patete’s dream of a church that would unite them never came to fruition. At the height of its success around 1915–18, when it had up to 18 ministers and bishops, it was still centred in Marlborough and Wairarapa. Its subsequent decline coincided with the emergence of the Ratana faith. Following T. W. Ratana’s visit to Marlborough in 1921 its adherents and ministers, including Taiawhio Te Tau, joined the new faith, the Anglican church, or their original churches. Patete remained a leader until his death. The church now has few, if any, adherents.

Haimona Patete was also active in secular affairs. By 1896 he was the acknowledged leader at Ruapaka pa. He organised and chaired a series of hui there, was involved in hui in Wairarapa, and helped rebuild the marae at Uruotane with Hamuera Tamahau Mahupuku. In 1896 Haimona and Meihana Kereopa unsucessfully petitioned the government for land for farms for the people of Ngati Kuia and Rangitane, and in 1896 he was chosen by his community to represent them in the Kotahitanga parliament. In 1902 Haimona presented a greenstone mere to the mayor of Blenheim as a sign of the loyalty of Ngati Kuia, Rangitane, Ngati Rarua, Ngati Koata and Ngati Awa to the newly crowned King Edward VII; he received a silver-embossed walking-stick in return. That year Haimona moved the venue of his hui to Waikawa. He himself moved to Mint Bay, in Queen Charlotte Sound, to support the local hapu of Ngati Kuia and Rangitane and to teach them farming skills. In 1904 he was present at a hui to raise a monument to Hamuera Mahupuku, leader of the Maori community at Papawai, and signed the petition to the government for funds.

Patete was a supporter of both the Liberal party and the Young Maori Party. He adhered firmly to the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi, wishing to achieve local self-government and reforms based on Maori initiatives. As a proprietor of Matuhi from 1904, Haimona used this and other Maori newspapers to publish material pertaining to the church and his political affiliations.

Patete was active in the local councils set up under the Maori Councils Act 1900, and the Maori Lands Administration Act of the same year. They were intended to provide a small measure of local self-government for Maori and to enable them to deal effectively with their lands. Patete believed that the councils saw to the secular needs of the people while the Church of the Seven Rules saw to their spiritual needs. In 1904 he was appointed council adviser for the Arapawa District Maori Council. Lack of funds undermined the work of the Maori councils, which had virtually ceased functioning by 1910, while political pressure forced the native minister, James Carroll, to drastically modify the composition and powers of the land councils in 1905.

Patete was active in the Liberal and Labour Federation of New Zealand, and encouraged local hapu to join. However, the establishment of the branches was not always a smooth process and while Patete had successes, such as the enrolment of Ngati Rarua and Rangitane in the Wairau district, he had difficulties with Ngati Kuia and others. Ngati Kuia believed that Haimona had overstepped his powers, while others could not see the benefits of forming a branch or opposed the idea altogether.

Patete’s involvement in the federation is probably best seen in the light of Premier Richard Seddon’s standing in Maori society as a parent figure who was often sympathetic towards Maori land issues. Patete became secretary to Te Ropu Mahi Atawhai o Niu Tireni, the Maori section of the federation. It established two Maori branches in Picton and Wairarapa; Patete was to represent the Picton branch at Seddon’s funeral in 1906. In 1903 he tried, unsuccessfully, to elicit the support of the Maori King, Mahuta, for Te Ropu Mahi Atawhai.

In 1911 Haimona ran, unsuccessfully, against Charles Rere Parata for the Southern Maori electorate. Thereafter he retired politically, but retained his involvement in his church. By now he and his family resided at Picton and often fostered children. Haimona was invited to Rotorua in 1920 to meet the prince of Wales, and was presented with a medallion. He died at Picton on 25 June 1921, survived by his second wife and his son. He had a large tangihanga and was buried at Waikawa cemetery.

Haimona Patete was one of the new Maori leaders who sought to work with, rather than against, the colonial government to achieve Maori aspirations. He also sought to provide his people with Pakeha skills and knowledge while his church sought to unify the Maori race. If neither his political nor religious objectives were fulfilled in his lifetime, he is still important for the example he set to others.