Read before the Wanganui Philosophical Society, 13th May, 1912.

Source: Downes, T. W. ‘Life of the Ngati Kahu-ngunu chief Nuku-Pewapewa’. Transactions and Proceedings of the New Zealand Institute 45 (1912): 364—375

Looking through a fine collection of manuscript waiata with the greyheaded Native owner, and noticing the frequently occurring name of Nuku, an inquiry concerning this (to me) unknown but great chief of the Ngati Kahu-ngunu brought to light the following history.

When Nuku was a little lad he developed an extraordinary gift for mimicry, which led him into many a scrape, for his fellows did not like to be mocked, and so young Nuku very often had to put up with bruised face and battered limbs; but the result of this jesting was that he quickly learned to protect himself, and became a great fighter as he developed size and strength. He gloried in his power, till at length none of his people could stand against him, for he was master every time. Even the big fellows and fighting-men had to yield to him, and he soon became the acknowledged leader of his people and captain of the war-parties.

Now he was a leader he wished to become a tohunga as well, but as this was forbidden him he gained by stealth what he could not obtain by power, for one evening, after dark, he crept quietly into the whare-wananga before the tohunga and their pupils came in, and endeavoured to hide himself in one of the dark corners of the building. Soon the priests came in and commenced reciting their genealogies and karakia, but the fire burned brightly, and before they had gone very far they discovered young Nuku crouching in the corner. It was no good asking him what he was doing there, for they could not turn him out after having heard and seen so much, so they gave him a position near the middle of the house apart from the chiefs’ sons, and there he sat with his back against the poutoko-manawa (main pillar of the house). Night after night he returned to his seat, till one evening the seventy students who were under instruction got up one by one to repeat the wananga. However, they all failed to go right through without a mistake until Nuku tried, and lo! he was able to repeat every word. By this test he again added to his quickly growing fame, and went out a tohunga as well as the chief leader among his people.

When he had fully reached man’s estate his first act was to build a pa strong enough to resist all attacks, and with this in view he chose a point on the Rua-mahanga River, Wairarapa (about two miles from Mr. Morrison’s place, and opposite Mr. Wall’s station). This naturally strong position, nearly encircled as it is by the river-cliffs, he carefully, fenced all round with high protective works, and across the neck of the peninsula he ran two rows of palisading, about half a chain apart, with a deep moat between. But his crowning work was carrying an underground passage from the middle of the pa to the moat, and from thence inland. In this way he could send a messenger unseen from the moat down the cliffs by an aka-tokai vine, which was always kept handy; or, if pressed very hard, he and his company could escape unseen by way of the underground passage, the outlet of which was hidden by earth and vines in a dark bush. This pa was called Nga-mahanga (twins), because of the underground roads, and was large enough to contain some small kumara plantations, as well as all the stores, and a garrison of one hundred men. He kept one hundred picked men in the pa, because he could move quickly with a small company, and he did not need to make so much provision for kai. Occasionally he had a few more men, but he endeavouerd to keep his strength about one hundred. This pa was never taken.

His first experience of actual warfare was at the Maunga-raki pa, on the Wainuioru River, which place he took, though considered by all to be impregnable. There was no road down the cliff to the pa. There stood Nuku with his hundred men above, looking down. Ah! but he had to be satisfied with a look, for he could not get down. So thought the people of the pa, and slept with the thought of their usual security. But Nuku considered, and then he acted. He built a huge raupo kite, something in the shape of a bird with great extended wings, and during the darkness of night he fastened one of his men to this manu and floated him over the cliff by means of a long cord into the pa below. The man quietly opened the gates, and when all was ready, at a given signal, Nuku let down his men, four and five together, by means of a tokai vine, and before morning the pa was taken. The people of the pa were the Ngati Hau-moana, the Ngati Waitaha and the Ngati Tama-wahine, under the chiefs Toko-te-rangi and Haupapa-o-te-rangi, the latter being captured. When taken, the conqueror spread his mat on the ground and invited Hau-papa-o-te-rangi to sit upon it, which he did, thus saving his own life and upwards of four hundred of his people.

His next exploit was at the Oruhi pa (at the mouth of the Whareama River, near Castle Point). Two men of the Hamua (a subtribe of the Ngati Kahu-ngunu), named Hautuhi and Tohi-te-oru-rangi, were killed, and a great army of two thousand men gathered together to obtain utu.

They reached the Oruhi pa, but as the place was well fortified and protected they camped for several days, unable to effect an entrance. Then a chief named Te Hiha called out that he would challenge the people of the pa to combat; so he selected three hundred of his bravest men, and another chief called Rangi-hui-nuku selected two hundred more, making five hundred in all, and this party separated from the main body and advanced, in the hope that their challenge would be accepted. (Te Hiha, of the Ngati Ira Tribe, was a great warrior who did much fighting at Wairarapa; he was the author of the following saying:—

Ma te huruhuru te manu ka rere,

He ao te rangi ka uhia,

He rango te waka ka mania.

By feathers does the bird fly,

By clouds are the heavens covered,

By skids does the canoe slide along.

The modern meaning of which is, “Money is the sinews of war.”

A rough idea of Te Hiha’s period may be obtained from the following genealogical table:—

The two challenging chiefs were not disappointed. Tu-te-whakarua-a-nga-rangi, the leading chief in the pa, likewise selected five hundred of his best men, and formed up to meet the invaders. Not only did he meet them, but he beat them, and drove them into the river; indeed, if it had not been for the river they would all have been killed; as it was, many saved themselves by swimming across. Both the assaulting chiefs escaped, but Te Hiha was afterwards known as Te Hiha-moumou-tangata (Te Hiha, waster of mankind).

Now, although this portion of the army was badly beaten, there were still the fifteen hundred men under Nuku, who were very anxious to strike immediately, and so obtain utu for their late companions. But Nuku said, “No; wait. When night comes lay ambuscades in the flax on both sides of the track, and in the morning you will find utu enough and to spare.” When night fell Nuku sent his companies up the hill, and placed them in various divisions in hiding on both sides of the road leading from the pa, to the camp, which was about two miles distant, and when morning broke he sent another three hundred men with the apparent intention of attacking the pa.

Now, when Tu-te-whakarua saw the three hundred approaching he sent out six hundred of his best men to meet them, and as Nuku’s men drew near the pa the companies met, and a general scramble took place. Then Nuku retreated towards his camp, as though defeated, and all the people of the pa rushed out to join in the pursuit and participate in the victory, for the people of Oruhi were hungry: they had been besieged for several days, and now they thought the opportunty to obtain provisions was before them. But they knew not of Nuku’s men in hiding, who waited till the people of the pa were busy pursuing, and then they took them in the rear. Great was the killing. And now the fame of Nuku was established, and his name was spoken everywhere.

Soon the people in the north heard of his great mana, and they sent a message to him for help, as they were in a bad way. The Ure-wera, Whaka-tohea, and Ngai Tai people had attacked the Gisborne district, and its people were in bondage.

When this message reached the Ngati Kahu-ngunu in Hawke’s Bay and Wairarapa, Nuku agreed to assist; so he and another chief, Pareihe, wh0 lived at Te Roto-a-Tara, travelled to Gisborne with one thousand men, and there they attacked a strong pa on the Waipawa River (near Gisborne), and, although the pa contained between six and seven thousand men, Nuku was victorious. (This battle was fought with Maori weapons, and took place about 1825.)

When the news of this great victory was spread abroad Te Kani-a-takirau, of the Ngati Porou Tribe, sent the chiefs Houkamau, Tama-nui-te-ra, and five others to ask Pareihe and Nuku, as leaders of the Ngati Kahu-ngunu, to help them take revenge against Whanau-a-apa-nui, who was living beyond Whare-kahika, for this latter tribe had beaten them three times in succession, so now Te Kani sought help from the Ngati Kahu-ngunu. Pareihe and Nuku started off to help, and when they reached Nukutaurua (on the east side of Te Mahia Peninsula, between Wairoa and Gisborne), Te Kani gave them a great war-canoe, which took forty men to paddle, twenty on each side, also a calabash full of red ochre, two mats, and one dogskin mat called Tapu-nui (the name of the dog whose skin supplied this mat was Tapu-nui, hence the name of the mat). When the present was laid before them Pareihe asked Nuku what his opinion was—should they go forward or return. Said Nuku, “Never turn back when the voice of war is sounding in your ears.” A Nga Puhi chief called Te Wera-hauraki (who had settled at Nukutaurua and married a Ngati Kahu-ngunu woman) supported Nuku in his resolve, and so Pareihe was satisfied, and sent word to Kani-a-takirau to bring all the scattered people in from the back country, to establish camps along the road which they were to pass, also to have plenty of food, weapons, and waka ready, for the Ngati Kahu-ngunu war-party was hastening to their assistance.

Soon they came along, went right up to Toka-a-kuku, and there the fight took place, the Ngati Kahu-ngunu being victorious, four hundred of the enemy being slain. After the battle was over, a huge whata, or stage, was erected, long poles being lashed to upright supports, something like a great post-and-rail fence. Then the dead were tied together, one foot of each man, and in pairs they were thrown over the poles, making a solid wall of dead men, and because of this arrangement the battle was called Whata-tangata. Then all the captured slaves were placed under the whata, a captured chief called Te Koata-waho being placed on a mat in the centre of the group, but forward from them. This man was Te Kani’s uncle, and when Te Kani saw him he called out and said, “My uncle, I cannot save you; because of the many chiefs of the Ngati Porou which you have killed, you must die.” Then, turning round to the victorious war-party, Te Kani continued, “There is Te Koata-waho; you can do with him what you wish, for he is in your hands now.” Then one of the brave fellows of Ngati Porou, called Takituangia, got up and said to Te Kani, “I’ll take him and fight him man and man; we can’t kill him there sitting on his mat.” Then he handed him three weapons—a taiaha, a tokotoko, and a patu paraoa—and said, “Take your choice, for you must fight.” Te Koata-waho replied, “Give me a taiaha; I die by a chief’s weapon.” They stood up, fought, and the brave Takituangia was killed. Directly Te Koata felled his adversary he flew off, but was caught after getting about three miles, was brought back, and duly added to the whata-tangata. After the feast Nuku and Pareihe returned home, with their names sounding to the very heavens.

Besides the one described, Nuku had another strongly fortified pa, called Pahikatea, and he was at this place when he heard Tu-whare was coming down the coast with his pu. When Nuku heard of the approach of thetaua he shouted out, “Let them come; let them blow their pu; my men can blow pu also, and I will make more and greater pu than theirs, and meet them with their own weapons.” So spake Nuku, and he straightway set his men to work fashioning trumpets and making pu of flax-leaves. Then when the taua appeared he ordered his two hundred men to take their positions on the high palisading surrounding the pa, and blow with all their might. But when he saw them falling all around, struck down by invisible means, with blood trickling from the wounded, he discovered that his pu were not a match for the pu-atua of the invaders, so he called to those of his men who remained to come down from their conspicuous positions and take refuge within the pa.

That night he placed one hundred of his men in hiding in one of the trenches of the pa, and next morning, when Nga Puhi came up to renew the attack, up jumped Nuku and his hundred men and quickly turned the tables, killing many, and capturing seven men, also three guns, which he named Pahikatea after the pa,*2 Waiohena after the creek where the capture took place, and Pu-atua (devil’s gun), the name given by him to the new weapon. He also took some ammunition from the dead men, and kept the captured slaves alive to show him how to use the guns. After a week, or perhaps a fortnight, Nuku arranged with his captives to show him how to load and fire; but they, cute fellows as they were, drove the bullet home first, with the charge of powder on top, and when Nuku found he could not fire as they could the slaves declared the guns were tapu, and only made for killing men.

Nuku, only too anxious to try his new weapons, made war on the people of Moawhango (Wairarapa), and here, as at the practice, the guns would not go off, being loaded the wrong way. During the excitement of the fight the seven Nga Puhi men escaped and got clean away, carrying the guns with them, for Nuku, when he found his guns would not go off, quickly discarded them and fought with his old Native weapons.

It was after this that Nuku decided to take his people to Nukutaurua, to be nearer European trade, for whalers had commenced operations in that district, and, in exchange for maize, pigs, and flax, guns and ammunition were obtainable. This was three years after the Whata-tangata battle was fought in the north.

As soon as Nuku left the district the Ngati Toa, Ngati Awa, and Ngati Raukawa took possession of the Wairarapa lands, the Ngati Toa occupying round about where the town of Carterton now stands, the Ngati Awa taking Featherston, and the Ngati Raukawa the district round Masterton. When Nuku reached Napier he heard how these intruders had taken up their residence on his land, so he called together the chiefs of his party to talk the matter over. He himself was strongly of the opinion that they should turn back and chastise those tribes, but Tahae-ata got up and sang a song the subject of which was the folly of returning while the pu-atua were still blazing. However, as Nuku had decided to go, some of the subtribes of the Ngati Kahu-ngunu agreed to accompany him. The Ngati Tokoira, Ngati Kurakuru, Ngati Hinepare, and the Ngati Kore gave four hundred men, who, with his own two hundred, made in all an army of six hundred strong. They journeyed back without incident, and when they reached Munga-raki (Mr. Buchanan’s property) they rested under a great rata-tree. They reached that place at midday, and after kai Hapuku asked Nuku and the other chiefs to climb a very high hill in order to survey the situation. From the top of this hill they could see from Masterton to the lake, as well as both the east and west sides of the Rua-mahanga River. They reached the top about sunset, when they saw the innumerable fires of the various interloping companies below, stretching right from the mouth of the lake to Masterton. After surveying the scene in silence for a time, Hapuku said to Nuku, “Where are we going to get enough water to put all these fires out?” Nuku replied, “If you are frightened, return at once, and I’ll put the fires out myself.” Then a korero took place, and all the chiefs of the party advised Nuku to return, as the fire was too great to be extinguished; but Nuku replied to every argument that he would see them put out or die on his own land.

Next morning the main body left Nuku with his two hundred fighting-men; but a few hours later one of the chiefs, named Hoiroa, of the Ngati Upokoire, returned with twenty-five of his followers, saying, “As you are going to stay, I also will remain.”

After two days had been spent digging fern-root and preparing food, Nuku and his party went to Puku-maki, from which place they again looked down on the fires. Then Nuku discovered that there was only one great fire, all the rest were small and insignificant, so he concluded that the most people were to be found where the great fire was burning. He started off that night, and came to Featherston, where there was a bush called Pikoke, and when he reached the shelter of this place he set his men to work and placed snares for rats all through the bush. Next morning the traps were visited and the rats cooked before daylight, and after kai they all went on to Tau-whare-rata, where the large camp-fire had been seen.

It was summer-time, in the early morning, and the occupants of the pa were all asleep. Nuku now arranged that twenty men should creep up to each of the nine houses composing the pa, and his instructions were that the principal men should be captured, and none killed, as he wished to make a peace after getting the chiefs into his power.

Accordingly the nine companies crept along in the dim light of the early morning, reached the houses, held the closed doors, and trapped the enemy. Out of that company only one man escaped—namely, the chief Whare-pouri—and he got away owing to the sides of his house not being driven into the ground and fixed like the rest of the whare. Nuku and two of his friends were watching the outcome of the attack, when they saw Whare-pouri creep under the side of his house, and flee. They watched him climb the bank, and they noticed by the dress he wore that he was a chief of note. Accordingly Nuku sent two of his fleetest men after the fugitive chief; but it was of no avail. When they at length caught up to him he saved himself by jumping over the cliff. In his descent he caught or was caught by a pohue vine, which saved his life by breaking the force of his fall, and eventually he got away to Pitone. When his pursuers came up they dared not venture the same feat, and had to return crestfallen and declare themselves beaten. In this exploit Nuku captured twenty-seven persons, including Te Ua-mai-rangi (the wife of Whare-pouri), also his eldest daughter (whose name was Te Kakape); and when he had got them together he launched the great canoe called Nga-toto, put all his captives on board, and took them to Otauira, sending most of his own people by land. Here he left the waka and went to Nga-mutu-awa (Bishop’s reserve for college at Masterton), where Nuku said to Hoiroa and the rest of the people,

“As Ngati Kahu-ngunu went back with fear because of the great fire on my land, and because I was thus weakened, I thought it the better plan to make peace, and that is the reason why I have saved these people from death.” Then, turning to Ua-mai-rangi, he continued, “Go home to my friend Whare-pouri and ask him why he came all the way from Maunga-tautari*3 (at Waikato) to kill me and take away my land. I am now on my way to Nukutaurua, but will come back again when I am armed with the pu-atua.”

When Te Ua-mai-rangi heard that speech she stood up and replied to Nuku, saying, “You have saved me; because of this I give you Te Whare-pouri’s eldest daughter, Te Kakape, and, as you have made peace, I leave my daughter and return to Whare-pouri to tell him what you say.” Then Nuku provided twenty of his people as an escort for her, and conducted her as far as Mataraua (the river near Carterton Station), where they parted, and she went on with her own people. At dark she reached the place where the Pencarrow Lighthouse now stands, and by the time she reached Pitone it was after midnight, and all the people in the pa at that place were asleep. Then she left her own people on the beach, and went in search for her husband, Whare-pouri. She listened at each house for her husband’s heavy breathing, and when she discovered the house where he was sleeping she entered. The fire was burning dimly, but she detected her husband and, quietly walking up to him, she placed her hand on his head, at the same time bending down and whispering, “Here I am alone, saved by Nuku.”

Hearing the sound of voices, the rest of the people woke up, and when they discovered it was Te Ua-mai-rangi who had come to them during the night they wished to tangi; but Whare-pouri said, “Wait till we hear the whole matter on the morrow.” When morning came Whare-pouri blew the trumpets and gathered all the people together, and then Ua-mai-rangi told what had happened, what Nuku had said, and how she had given her daughter to Nuku. Then Whare-pouri got up and said, “I want all the Ngati Toa, the Ngati Awa, and Ngat: Raukawa to leave this valley, for Nuku is right. Why did I come here? Was it not because Te Rau-paraha and Rangi-haeata advised me that the land was idle? I want you now to give your consent, so that I may go to Nukutaurua and bring Nuku back to his own land, and I and my people will then go back to Maunga-tautari.” Then all agreed to this proposition, with the exception of Taringa-kuri, of the Ngati Tama, who had come from Poutama, near Mokau, who said, “No; I shall not leave; I have lost some of my people here, and will never go back.”

Wiwi-o-te-rangi, of Ngati Raukawa, spoke next, and he said to Whare-pouri, “I agree with you, and will order all my people out of the district.” Rangi-hei-roa, chief of Ngati Toa (uncle to Wi-parata), also agreed with Whare-pouri’s plan, and said, “My people will also leave this land, and go back to Waikato.” When Whare-pouri saw the feeling of the chiefs he turned to. Taringa-kuri and said, “We all go; you can remain to light Nuku’s fire; stay as firewood for him.” Taringa-kuri replied, “I’m green wood, and won’t burn.” Whare-pouri then said, “I shall go to Nukutaurua by ship; I want you, my people, to gather pigs and corn in abundance, so that we may fill the ship in payment for taking us there.” He afterwards found the captain of a ship who was agreeable to undertake the expedition, and he eventually set sail.

In the meantime Nuku was on his way back to his new home, and when he reached Wai-marama (a well-known block of land, recently sold by the Government) Te Hapuku came to meet Nuku, and after the greeting he said, “This young person you have with you is a fine girl; I want her, and have come out to get her.” Nuku replied, “This is the fire that you were frightened of, and could not put out; I put it out myself.” Then Te Moana-nui asked Nuku for her; but again Nuku refused, saying, “She was given to me to make peace, and I wish to send her back to her father.” He then called the Ngati Kahu-ngunu around him, and when they had gathered he said, “This lady is Whare-pouri’s daughter, given me by Te Ua-mai-rangi in order to make peace between us. You now see her; there she is. I want you to give her mats and greenstone, and send her back to her father.” Then the people all shouted for joy, agreeing to Nuku’s proposals, and they gave her fifteen mats and a celebrated greenstone called Kai-kanohi, and then raised an escort of thirty men to see her safe as far as the place where the Pencarrow Lighthouse now stands. When this place was reached twenty-eight of the escort were sent back, but the two leaders, Paranga-rehu and Te Aketu, still acted as her bodyguard, saying, “We will stay with you whether you are safe or not.”

When the party reached the pa the girl called out, “Whare-pouri, where are you?” and the father, recognizing his daughter’s voice, said, “Surely it is my child; I will go to meet her.” As he went out the girl’s two companions hung behind, until they were about 2 chains away, for they did not wish to intrude while the two met. When the father and his child were clasped in the usual hongi, Whare-pouri whispered, “Is this an errand of peace, or did you escape?” and Te Kakape answered, “I came on a mission of peace, and Nuku’s two men are just behind; save them.” Then Whare-pouri, in obedience to his daughter’s words, hongied with the chiefs, and they were saved.

Before Nuku sent his escort south with Whare-pouri’s daughter, one of the leading chiefs of Hawke’s Bay, named Pareihe (previously mentioned), said to Nuku, “I find you are a brave man; the way you challenged Ngati Toa, Ngati Raukawa, and Ngati Awa, and put out their great fire, proved that. Now there is a great fire at Roto-a-Tara (Te Aute), with smoke rising to the very sky. Te Heuheu (of the Ngati Tuwharetoa) has taken possession, and has started that fire. You asked my people to help you quench the great fire at Wairarapa, but they left you, frightened. Yet I come to you for help, for who else can put this fire out?” Nuku replied, “Let us first go to Nukutaurua; we must have pu-atua before we can fight Te Heuheu, for he has got them.” As Pareihe was agreeable to wait, they went to Nukutaurua and spent two years breeding pigs and growing maize to give in exchange to the traders for pu-atua. At the end of that time an army of six hundred men left Nukutaurua, and travelled to Te Aute, where very many of the Waikato, Ngati Raukawa, and Ngati Tuwharetoa were killed, the great chief Te Momo*4 being among the number. Afterwards Te Heuheu came back to Hawke’s Bay seeking revenge for his losses, but in the battle of Te Whiti-otu he was again defeated, and the chief Tanguru slain.

Nuku had not long been settled in his new district when Ngati Porou sent Te Potae-aute, one of their chiefs, asking for aid to obtain utu from the Tolaga Bay people, Te Rere-horua having been killed at Toko-maru, on the East Coast. The answer he received was, “We never like to fight at the back of the house: outside, all right; but inside, never” (probably meaning, could not fight within Ngati Porou boundaries).

Being unsuccessful, Potae-aute went on to the Arawa people, and interviewed their chief Taraia. After considering the proposition, Taraia said, “You go on to the Waikato people: if they will help you I’ll follow; if not, I won’t go, as it is a risky business, and the distance is too far to walk.” So Potae-aute went on to Waikatc, where he met the chief Paiaka, and after having explained the object of his journey Paiaka said, “You require a very great war-party for this business, and the distance makes the thing bad; however, let us go on together to Taupo, and see what Te Heuheu has to say about it.” They journeyed to Taupo, and when Te Heuheu heard of the affair he decided not to form, an opinion till he had talked the matter over with Whata-nui, of the Ngati Raukawa, and Pehi-turoa, of Whanganui. So Te Heuheu sent for Whata-nui and Pehi-turoa, and when they met to consider the position Whata-nui said, “The Hawke’s Bay and the Wairarapa people both killed my people at Roto-a-Tara (Te Aute), where we lost Te Momo (the great chief allied to Ngati Raukawa, Ngati Tuwhare-toa, and Ngati Maniapoto); because of this I will join you.” Te Heuheu said, “Because of the beating the Ngati Kahu-ngunu gave me at Te Whitiotu and Manga-toetoe (in the Hawke’s Bay district), I’ll consent to take revenge.” On hearing this, Pehi Turoa also consented to join; so the three said to Potae-aute, “Go back; gather up your people; be ready. We will travel by the Mohaka road to Wairoa, then on to Nukutaurua, where we will take revenge on the Ngati Kahu-ngunu before we go to make good your loss.”

So the war-party started off with a great army of a thousand men, arid when they neared Nukutaurua the people heard of their approach and started off in canoes to meet them. Near Gisborne they met. There were the Rongo-whaka-ata, the Mahaki-ngai-tahupo, and the Aitanga-hauiti; but in the battle which ensued at the meeting of the two forces these tribes were beaten, their chief Te Heke-tua-te-rangi and his daughter both being taken as slaves, the latter being captured by Te Heuheu himself. When these two were taken Whata-nui said, “Let me kill Heke-tua-te-rangi and his daughter for the blood of Te Momo” (utu). But Te Heuheu replied, “You shall not slay a man whom I captured,” and, turning round to the captive chief, he said, “Go home, and take your daughter with you.” Then said Te Heke-tua-te-rangi, “Now I see that I am saved by you, keep my daughter; I will come back to bring her home.”

He went home, and quickly returned with six slaves, a greenstone mere, and six mats. This present he handed over to Te Heuheu for saving their lives, saying, “Accept these slaves, mats, and mere; give me my daughter and I’ll return, and may the sun shine between us for ever and ever.” To this speech Te Heuheu replied, “My foot shall never step into this valley, and I will also warn my people lest they offend”; and thus they established a friendship which was never broken.

After this Te Heuheu came to the pa where Nuku and Pareihe were dwelling, and called out, “Where are Nuku and Pareihe?” Then went Nuku and Pareihe outside the gate, and called back to Te Heuheu, “Here we are. What do you want?” Then said Te Heuheu, “When are you coming out to meet me in fight? I have heard a lot about your bravery in’battle, and have followed you up with the intention of fighting, but there you are, sitting in your pa like owls in the supplejacks.” Pareihe, answering, said, “Are you not satisfied with the great heap of dead men you have slain—enough to keep you and all your force in food for twelve months? What more do you want? Go, return to your own land.” Te Heuheu replied, “When you see the clouds all red in the sky you will know that I have returned with all my party (a threat to burn all the pa as he returned), but the thunder of my footstep will I leave behind for you to hear.” Pareihe again answered, “This is a foreign land, not my own home. Why do you wish to fight in a strange land? But listen: the thunder of your footstep will I follow, and may be you will then obtain the satisfaction of fighting me.” Te Heuheu lifted his arm, so as to signify his acceptance of the challenge and terms.

When the harvest of kumara had been gathered in, Pareihe and Nuku went on to Taupo to redeem their promise–to follow the sound of Te Heuheu’s footsteps. They conquered the Taupo people at a battle called Omakukara, on the west side of Taupo, where they killed four hundred, and piled them up in a great heap, presenting the pile to the daughter of (here the narator’s memory was at fault). Then on the war-party went to the southern end of the lake, in order to find Te Heuheu himself. Te Heuheu was at this time on an island in the lake (probably Motutaiko), and when he saw the great war-party at the side of the lake he said to his people, “Who can stand against that forest? It is not policy to throw our lives away when we see danger”; and turning to his daughter, Te Rohu, he said, “Go to the people of Ngati Kahu-ngunu, for my life must be saved through you.” His daughter answered, “Why, would you give me up to be killed?” Te Heuheu replied, “Not so, my girl, for your mother is closely related to them.” So he sent Te Rohu with six men; but before they went he caused to be tied round the forehead of each the symbol of peace (the broad part of the flax tied round in a circle for the head, and finished with a sort of bow in front).

Then the seven left the island and met the war-party at Tauranga-Taupo (a river on the eastern side of the lake), and, after the greeting was over, Te Heuheu said, “Come hither Pareihe, Nuku, and Te Wera; you have fulfilled your promise made at Nukutaurua, for you have followed me, and have made your mark in my lake. No other tribe has ever been able to establish such a mark, so now we will make peace for ever, for our daughter made peace, and a woman’s peace is a lasting peace: Remember.”

Pareihe, noticing a kawau (shag) sitting on a stump in the lake, said to Te Heuheu, “Is this true what you say?” Te Heuheu replied, “Yes.” Then said Pareihe, “If I shoot that shag with this new weapon [he had a gun] it will certainly be a true peace.” He raised the gun, and the shag fell.

After this the taua returned again to Nukutaurua, and shortly after they reached home they heard that two men and a woman had been killed by Rangi-tane. The names of those kilted were Paia (Te Moana-nui’s mother), Pae-rikiriki, and Te Hau-waho, and they were killed by Whata-nui in revenge for Te Momo. When the news reached the peninsula Pareihe stood up and said to Nuku and his people, “I shall want your help, for we must obtain utu from Rangi-tane.” So off they started for Hawke’s Bay and other Rangi-tane lands, and as they went along victorious they captured the principal women of Rangi-tane as slaves, and killed many of their men; the principal slaughter taking place at Te Ruru, on the Manawa-tu River (near Dannevirke).

Then they returned, carrying the captive women with them. Among those taken were the two daughters of Kai-mokopuna. The chief Hapuku married one of these, and their son’s name was Te Watini Hapuku. No revenge was ever obtained for these victories.

In the meantime Whare-pouri had been growing corn and preparing flax in order to pay for the passage by boat for himself and a number of his people, and they set out for the peninsula to seek Nuku.

While they were in the boat journeying up the coast it so happened that Nuku set out in a large canoe for the place where the town of Napier now stands, and when they were all out to sea a violent gale arose and the canoe was capsized. Eighteen persons were thus drowned, but Nuku and four others climbed on to the upturned canoe and waited for the tide to wash them on shore. Poor fellows, half-dead by cold and exposure, they vainly struggled, endeavouring to keep her prow straight on to the shore, as swiftly she was being driven to destruction. While Nuku was swimming at the prow, striving to bring her round, a strong wave drove the canoe right on him; he was struck on the head, and in a moment was dead.

When Whare-pouri landed from the boat on which he had journeyed north he found that the man he had come to seek was dead, so he inquired who was the nearest relation to the great chief. Tu-te-pakihi-rangi came, stood up and welcomed Whare-pouri with the customary salutation, and then asked why he had come. Whare-pouri replied, “I came hither to see my friend Nuku, and invite him back to his own place at Wairarapa, for I am heeding his message, and am leaving the land for my old, home, taking my people, the Ngati Awa, with me. The Ngati Toa and the Ngati Rau-kawa are also removing; but Taringa-kuri and his people, the Ngati Tama, are still at Featherston, where I have left them as firewood for Nuku’s fire. I find my friend Nuku is dead, but I still wish all you of the Ngati Kahu-ngunu to go back.”

Then Te Hapuku said to Whare-pouri, “I cannot allow my people to go back with you to Wairarapa, for when you get them there you may kill them in revenge for past fights.” Whare-pouri stood up and said, “I am a chief by birth, and my word is the word of a chief. If you are frightened I am prepared to stay with you as a hostage while your people go; then if any of them are killed you can kill me.”

Then Whare-pouri, with fifteen of his warriors, stayed at Nukutaurua, while Tu-te-pakihi-rangi and twenty Wairarapa chiefs (here my informant recited the twenty names) went on board the same boat that had brought Whare-pouri, and sailed back to Po-neke. When they landed at that place a great meeting was called, at which Tu-te-pakihi-rangi stood up and said, “We have now a new people amongst us, and they are armed with this new and strong weapon against which our weapons are useless. Because of this, I shall ask you to retire back to your own land, for who knows what lies before us? Listen: my boundaries will be from the Manawa-tu River to the Manga-toro Creek (a tributary) on the east side to its source, thence over the land to Rapu-ruru, and on to Aketiu, round the coast, back to the Manawa-tu River, where the boundaries meet. This land shall be mine, for me and my people. See the Tararua Mountains, which divide the land: let that range be our backbone, and all the rivers and creeks which rise in that backbone and flow west will be water for you to drink from; those flowing east will be for me and mine.”

Then all the people agreed to these proposals, and they stayed and lived together in peace.

Note.

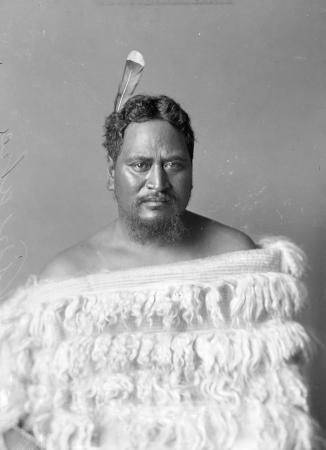

Nuku-pewapewa was so named because his face was tattooed with a pattern called pewapewa. It consisted of a single curve round the eye, a spiral on the nose, and three lines curving from the nose to the chin. A carved figure representing this chief, bearing his peculiar moko, is to be found on one of the corner-posts of the palisading at the Papa-wai pa near Greytown. He is credited with being a man of extraordinary height, and in a cave called Hui-te-rangi-ora, on the Nga-waka-a-Kupe Hill (about four miles east of Martinborough), there is or was to be seen his mark. Here the Native chiefs for many generations dipped a hand in kokowai and struck the wall as high as possible; Nuku’s mark is a clear foot above all the rest. He was drowned about 1840, and at Te Whaka-ki, on the beach at Wairoa, where the accident took place, his canoe was carved and erected as a monument, “And” (said my informant) “it is still there, or was there when last I visited the spot.”

[Footnote] *1 The great chieftainess of Ngati Ira, killed near Kai-koura.

[Footnote] *2 This took place at Te Tarata. Pahikatea is about three miles north-east of Papawai.

[Footnote] *3 My informant has evidently made a mistake here, for Whare-pouri came from Nga Motu, New Plymouth, where he was the head chief of the Nga Motu hapu of Ati-awa.

[Footnote] *4 See wars between north and south tribes, Poly. Soc. Journ.