Kopuaranga papakainga

Kopuaranga Papakainga

Kupe

Kupe was a great chief of Hawaiki (Tahiti), whose father was from Rarotonga, and whose mother was from Rangiatea (Ra’iatea), where her father lived. These were the three islands over which Kupe’s mana (power) extended.

One day Kupe’s fishermen went out with lines and hooks to their traditional fishing grounds. After a long time without any bites, the fishermen hauled up their lines and discovered that the bait had been taken. They put on fresh bait and lowered their hooks again, but the bait was taken again and again until all of it gone. They returned to shore and reported their lack of success to Kupe.

After a time, on another day, the fishermen went out again; the result was the same; their bait was taken from their hooks, and they returned home without a single fish. The fishermen reported their ill-luck again, and much discussion took place as to the cause of it. They finally decided to lay the matter before the priests (tohunga). The priests said that if the people planned to go fishing again, the lines and hooks should be blessed.

When morning came, the people decided to go fishing again, so the lines and hooks were brought to the priests, who said the proper prayers (karakia) over them. Then the canoes put out to sea. The fishermen now discovered numerous octopi were taking the bait from their lines; they also saw the great octopus of Muturangi floating on the surface of the sea. They realized Muturangi was causing the trouble and fearing him, they all returned to shore.

On arriving they reported what they had seen to Kupe; so Kupe went to Muturangi, who lived at Kahu-kaka, and told him, “O sir! You are the cause of our ill luck!”

Muturangi replied, “I know nothing about your problem.”

Kupe then said, “Restrain your great octopus; do not let it go to sea. The canoes plan to go out fishing again tomorrow.”

Then Kupe returned to his home at Pakaroa and told his people to prepare for fishing the next day, as food was getting scarce. The next morning the fishermen of Pakaroa went out, but the bait was taken again; the great octopus had not altered its conduct. The fishermen returned and reported that the octopus of Muturangi was still there. Kupe again went to the priests. He described the problem and asked the priests what should be done. They replied that they were not powerful enough to overcome the action of the octopus, so Kupe should ask Muturangi himself to stop its doings.

Kupe said, “I intend to slay Muturangi.”

The priests replied, “Even if you slay Muturangi, the octopus will still retain its power; it would be better to kill the octopus instead.”

Kupe then went to the house of Muturangi, and again complained of the evil conduct of the octopus; “I come to ask you to restrain your pet, or I will kill it.”

Muturangi replied, “I will not allow my pet to be killed. The sea is its home; the people are wrong in going there to fish.”

“If you will not restrain your pet, I intend to kill it.”

“You will fail.”

“So be it.”

Kupe then returned to Pakaroa, and said to his people, “Prepare my canoe for sea.” So the canoe Matahorua was carefully prepared-the washboards at the bow were lashed on; two endpieces were put in place, one at the stern, one at the bow; and two stone anchors were brought from his grandfather, Ue-tupuke, who had charge of them. One of these anchors was a tatara-a-punga (coral) from Maungaroa, a mountain in Rarotonga, and the other was a puwai-kura, a reddish stone like kiripaka (flint) or mata-waiapa (obsidian) from Rangiatea.

After the anchors were placed on board, Kupe went out to slay the octopus. On arrival at the fishing ground named Whakapuaka, the lines were let down. They were hauled up before reaching the bottom, and then it was seen the bait had been eaten. The octopi followed the lines to the surface, where Kupe and the sixty men of the canoe Matahorua began to slaughter them. They continued to do so till night fell, while the great octopus of Muturangi was all the time waiting a little beyond. The body of this octopus was eighteen feet long, while its feelers were thirty feet long when stretched out. Its eyes were the size of the papaua-raupara (a thin, flat shellfish, like the pearl oyster).

After the slaughter had continued for a very long time, Peka-hourangi, one of the principal priests said, “Stop killing the octopi; if you could succeed in killing Muturangi’s great octopus, the others would all disappear, for he brings them here, and Muturangi is inciting them by means of incantations (tuata) to take your bait from the hooks. The fishermen therefore ceased slaying the smaller octopi and turned their attention to Muturangi’s octopus. But when the canoes tried to approach the monster, it made off to the deep sea. It was now night, so Kupe returned to shore, while Ngake (or Ngahue) followed the great octopus out to sea in his canoe, Tawhiri-rangi. On arrival ashore Kupe said to his men, “Put plenty of provisions on board our canoe, for we will follow this monster until we kill him.” The crew did as they were told.

On learning of Kupe’s proposal, Hine-i-te-aparangi, his wife, and her daughters, urged Kupe to remain and let his men pursue the octopus, lest he be overtaken by storms at sea and drowned. Kupe was annoyed at this and said, “Stop your wailing; you have prophesied ill luck to me (waitohutia), and it will end perhaps in my death. You must all board the canoe, so there may be one death for us all, and not me alone while you remain lamenting in safety ashore.” So his wife and five children consented to accompany Kupe and were with him when he discovered Aotearoa.

Matahorua was now launched and the voyagers departed. There were seventy-two people on board. After a time they reached Tuahiwi-nui-o-Hinemoana, where Kupe overtook Ngake and asked, “Have you seen the octopus?”

Ngake replied, “There! You can see him reddening (mura-haare) on the ripples of the sea.” Kupe looked, and it was so. They tried to approach the monster, but to no avail; the octopus only went on faster, directing his course toward this undiscovered island of Aotearoa.

Kupe said to Ngake, “The octopus is headed for some land apparently; by following it we shall be led to a strange country.”

Not long after this, an island was seen in the far distance, like a cloud on the horizon, toward which the octopus made straight. As the octopus drew near to Muri-whenua (the North Cape of North Island), it turned south along the East Coast. Kupe now said to Ngake, “Follow our fish; I will land here to rest and then come after you. If the octopus should stop anywhere, let it remain there until I come.”

So Ngake continued on in pursuit, while Kupe went on from the North Cape to Hokianga and stayed a while. In the course of his wanderings there in search of food, he came to a place where there was some soft clay (uku-whenua) into which his feet sank and left holes, as did the feet of his dog Tauaru. The clay eventually turned into rock, and both Kupe’s and his dog’s footsteps are to be seen there to this day. When Kupe and his children departed from Hokianga, they left the dogs behind because the dogs had wandered off into the forest to hunt birds. The dogs returned to the beach and howled; Kupe heard them, but he used a prayer to prevent them following, and they were at once turned into stone. [Two rocks at the mouth of the Whirinaki river, Hokianga, are still pointed out as Kupe’s dogs. Another account of these dogs is that Kupe decided to leave them there as guardians for the land, and he carved out of stone a male and female dog to represent them.]

After a long stay at Hokianga, Kupe sailed after Ngake and found him at Rangi-whakaoma (Castle Point), where Ngake was awaiting him. Ngake informed Kupe that the octopus of Muturangi was there within a cave giving birth to offspring. Kupe proceeded to the cave and broke it open, which caused the octopus to flee in the night towards the south. Kupe and Ngake then gave chase and came to Te Kawakawa (Cape Palliser, the southern point of North Island). This name was given by Kupe because one of his daughters here made a wreath of kawakawa leaves, and the name has ever since remained in memory of it. At this place is a kahawai spring where Kupe kept as provisions the fish of that name.

Near here the sail of the canoe Matahorua was broken, and Kupe, Ngake, and their friends proceeded to make another for the foremast. Kupe said to Ngake, “Which is the best kind of sail, yours or mine?” Hine-waihua, the wife of Ngake, “Ah! Your parent’s sail is the best; it can be made quicker; he has the dexterous hand for that kind of work.” So they set to work and continued on to daylight, all hands helping to make the sail-Kupe, his elder relatives, and younger brethren. When daylight came, the sail was to be seen hanging up on the cliff, which caused Ngake to say, “I am beaten by my friend.” [This enignmatic comment can be explained by the tradition that a competition in sail-making had taken place between Kupe and Ngake.

Near that spot is also a bathing place of Kupe’s daughters, one of whom, Makaro, was menstruating at the time, so the water remains red to this day. There also is a heap of stone, from the top of which Kupe recited his prayer to draw fish up for his daughters, among others, the hapuku, which ordinarily lives in deep water. He was gazing (matakitaki) on the multitude of fish; then raising his eyes, he saw beyond the sea the mountains of the South Island, the snows on Tapuae-nuku (“The lookers-on”) in the sun. Hine-uira, one of his daughters, asked Kupe what he was gazing at. He replied, “I was looking at the shoals of fish coming in; when I lifted up my eyes, I beheld an island lying there.”

Hine-uira said, “Let the name of these stones be Matakitaki” (“Gazing”), which remains to this day.

After this they started in pursuit of the octopus, going on to the mouth of Te Whanganui-a-Tara (Port Nicholson), on the west side of which their canoes landed. Here Kupe went for a bath, and afterwards stretched himself out on a rock to dry himself in the sun, where he scratched himself, hence that place was ever after called “Te Aroaro o Kupe” (i.e., “Te Ure-o-Kupe,” “The penis of Kupe”-the rock on Barrett’s Reef at the entrance of Wellington Harbor).

From there, after going to Hataitai (Miramar Peninsula) they went on to Owhariu (Ohariu, west of Wellington, on Cook Strait) where the sails of Matahorua were hung up to dry, hence the name of that place. (Owhariu means “to turn aside.”)

The two islands in Te Whanganui-a-Tara, named Matiu (Some’s Island) and Makaro (Ward’s Island), were named after two of Kupe’s daughters to commemorate their visit to these islands. (The two islands are in Wellington Harbor.) Kupe approved of the names. When they arrived at Te Rimu-rapa (Sinclair’s Head), they proceeded to gather paua (Haliotis), shellfish, and other kinds of seafood, and there dried them, as provisions for their voyage. Then they got some large seaweed, and made receptacles for these provisions, so that the food would not be spoiled by dampness. Hence that place was named Rimu-rapa (“seaweed flattened”; bull-kelp is still used as bags for preserving birds, especially mutton birds.)

They found Te Rimu-rapa a very disagreeable place because of the wind, so proceeded north to Porirua Harbor, where Mata-horua was anchored. Here, on the east side of the harbor, near the mouth, Kupe saw a stone which he at once desired as an anchor for the canoe; it was a kowhatu-hukatai (a white stone, probably volcanic). His daughters also had the same wish because of its excellence. The new anchor was named Hukatai (also Hukamoa).

Ngake now said to Kupe it was time they went after their enemy. So they left and went to Mana Island, where Kupe left his wife and his daughters for a while. Mohuia, one of Kupe’s daughters said, “Let this name, Mana, be retained for this island, in remembrance of our power and daring (mana) in crossing the ocean. Kupe gave his consent to this naming, saying, “Yes! it is well, Mana shall be its name.”

After leaving his family there, Kupe and Ngake made a straight course for Te Wai-pounamu (South Island), and when they drew near it, they saw the octopus of Muturangi approaching their canoes. The two canoes of Kupe and Ngake separated to allow the octopus to pass between them, which it did, the head rushing forward drawing its tentacles behind, which spread out even beyond the canoes. From head to the end of its tentacles, it was two hundred and forty feet long, while the body was twenty four feet wide. Tohirangi stood up in the center of Kupe’s canoe with a long spear and lunged at the monster. He speared it twice, and when it felt the pain, it stretched out its tentacles to break the spear of Ngake, who was using his spear from the other canoe. The two spears crossed, and the tentacles of the octopus seized hold of the gunwale of Ngake’s canoe, Tawhiri-kura, from bow to stern, which so frightened the men on board that the canoe was nearly upset. Then the tentacles seized hold of Kupe’s canoe, and Kupe took his axe named Ranga-tu-whenua and began chopping off the tentacles; but the octopus would not let go. Kupe then shouted to Po-heuea, “Throw the bunch of calabashes at the head of the octopus!” This was done, and the monster, thinking perhaps that it was a man, let go the canoe, and encircled the calabashes with all his tentacles. Then with his axe Ranga-tu-whenua, Kupe made a fierce downward blow (paoa) at the head of the monster and smashed in its eyes. And so died this great sea creature, the “Wheke-o-Muturangi.”

Now from this incident came the name of the South Island Ara-paoa, from Kupe’s paoa, or downward blow, on the head of the octopus. The rocks Nga-whatu (“The Brothers” in Cook Strait) became tapu, for that is the place where the Wheke-o-Mururangi was laid to rest. An incantation (karakia) was said to conceal the octopus lest Muturangi should come in search of his pet and revive it. Immediately after the incantation ended, swirling currents began around the rocks, so that no canoe could land there. The name of these rocks, Nga-whatu, refers to the eyes (whatu) of the octopus, and the spot has remained tapu ever since. When canoes cross the Straits to or from Ara-paoa, the priests say, “Do not look on Nga-whatu; cover the eyes with a shade, lest, looking, a gale of wind comes on and the canoes will be capsized.” This is the rule even to this day.

Now the above story explains why Kupe, Ngake, and their companions crossed the wide ocean and discovered this country of Aotea-roa. How great was the mana (power, ability, prestige, etc.) of Kupe to accomplish this undertaking! Hence it was that his daughters wished to emphasize this mana by naming the island on which they stayed Mana, in honor of their father Kupe. The name of Porirua harbor is derived from the fact that the voyagers left their old anchor there and replaced it with a new one named Huka-moa (or Huka-tai). (“Pori” refers to the exchange of one anchor for another.)

Now after these events Kupe proceeded to the southern island to determine its resources, and to see whether or not any people were living there; he also intended to do the same as regards to the northern sland. He went down the west coast of the southern island until he reached Arahura River (a few miles north of Hokitika, a town on the west coast). He gave the river that name because he went to search out whether any people were to be found there. [Ara-hura, “the way opened up”].

Kupe was the first man to discover the valuable pounamu, or green stone, in Aotearoa. The first specimen he saw was that kind called inanga, so named because it was seen in a river together with many inanga, or white-bait, which he proceeded to net. When Hine-te-uira-i-waho stretched forth her hand into the water to get a stone as a sinker for the bottom of the net, the one she got was quite different from any she had seen before, and so it was called inanga.

Kupe’s canoes then proceeded farther to the south, and finally reached the tail-end of the southern island, where Kupe said to Hine-waihua, the wife of Ngake, “O Hua! Leave your pets here to dwell at this end of the island, for behold there are no men here.” So the seals and the penguins were left to guard that end of Arapaoa, which is now called “Te Wai-pounamu.” It is well known that the proper salutation to the people of the South Island is “Welcome ye people of Arapaoa”-and Ngati-Tahu of the South Island welcomes us by saying, “Welcome ye people of the sunrise.” Nowhere did Kupe or Ngake see any people on either the southern or northern island.

On Kupe’s return to the northern island he went by way of the west coast to Hokianga. When he was off Whanganui he saw a very fine bay there, and so decided to land to inspect it. On entering the bay, the canoes landed on the west side and stayed a while. This place at the mouth of Whanganui, he named Kaihau-o-Kupe (“Kupe’s wind-eating”), because it was very windy while they were there.

Kupe paddled up the Whanganui River to see if any people lived there; he went as far as Kau-arapawa, so called by him because his servant tried to swim the river there to obtain some korau, or wild cabbage, and was drowned, for the river was in flood. So Pawa was drowned, and his name was applied to that place. (Kau-arapawa is about fifteen miles above the town of Whanganui.) Kupe heard some voices there, but as soon as he found these voices were only from birds (weka, kokako and tiwaiwaka), he returned to the mouth of the river, and then went on to Patea, where he planted some karaka seed of the species called oturu. While at Patea he tested the soil by smelling it, and found it to be para-umu-a rich black soil-and sweet-scented.

When Hine-te-ura, Kupe’s daughter, arrived at Hokianga, she said to him, “O Sir! let us take possession of this land,” to which both Kupe and Ngake consented. Then a feast (hakari) was made by his daughters at a place between Te Kerikeri and Whangaroa. At the end of the feast, Kupe, Ngake, and all their people proceeded to place the land under tapu (“uruuru whenua”; usually refers to “placating local gods”), prior to their return to Rarotonga, Rangiatea and Hawaiki. The stone of the uruuru-tapu is at the head waters of Hokianga, and is named Tama-haere, sometimes called Toka-haere; it is still very tapu. The feast was held at the place usually called Tarata-rotorua, where certain natural pillars of rock are said to have been the posts that held up the food at the feast. Hokianga means “Returning” in reference to the place from which Kupe left the island to return home.

Now, it must be clearly understood there were no people anywhere on these islands-not a single one. And Kupe left only his two dogs, named Tauaru, the male, and Hurunui, the female; none of their party remained here; everyone returned to Rarotonga.

After Kupe and Ngake returned to Rarotonga they went on to Rangiatea (Ra’iatea) and from thence to Hawaiki (Tahiti, though other sources say that Hawaiki was the ancient name of Ra’iatea). They reported their discovery: “There is a distant land, cloud-capped, with plenty of moisture, and a sweet-scented soil. It is situated at “Tiritiri-o-te moana” (“The vast space of ocean”?). When the people heard of the newly discovered lands, they desired to come here because a great number of quarrels had arisen among themselves in their homeland.

When Kupe reached Rangiatea, Nga-Toto (or Toto) asked him, “O Kupe! What does the land you have discovered look like? Is it raupapa (flat land) or tua-rangaranga (undulating?) Is the soil one-tai (sandy), or one-matua (rich, fertile)?”

Kupe replied, “In the center part are mountain ranges (tuatua); the spurs that come down to the sea are sheltered, and plains open out on both the east and west coasts. On the southern island, the ranges that come down to the sea on the west coast, have pakihi (flats, usually grassy) opening out here and there. The east coast is fertile and fine to look on. The soil is good, it is one-paraumu (rich, black soil); in some places it is one-papa-tihore, (i.e., subject to land slides), but the growth of plants is healthy and vigorous.”

Other people asked, “O Kupe! What do the seas and the streams contain?” He replied, “There are fish both in the sea and inland; paua (Haliotis), mussels, and cockles thrive along the shores of the ocean.”

Others asked, “What is the course the canoe should steer, O Kupe?” To which he replied, “Let it be to the right of the setting sun, or the moon, or Venus. Go during Orongo-nui (summer), in the month of Tatauuru-ora [November] when food is plenty.”

Turi then asked, “Which is the very best part of the land?” Kupe replied, “Leave the course in the current of Pareweranui (the strong south wind); there is a place of much ‘fruit of the land’ (i.e., birds, fish, and so on). (The narrative is obscure here, but we know that Kupe directed Turi to come to Patea River on the west coast of the north island).

Others asked, “Did you see any people on the land?” Kupe replied, “I saw no one; what I did see was a kokako, a tiwaiwaka, and a weka (i.e., birds), whistling away in the gullies; kokako was ko-ing on the ridges, and tiwaiwaka was flitting about before my face.”

Now Kupe and Ngake stayed a long time at Rangiatea and then went on to Hawaiki (Tahiti). They went there at the request of Ruawharo (a son of Hau, a nephew of Kupe who came to New Zealand in the Takitimu, says the Scribe). Ruawharo came to ask them to go to Hawaiki in order that the people living there might hear their account of the new land discovered by them at Tiritiri-o-te-moana.

On leaving Hawaiki they returned to Rangiatea where Kupe found Turi, who had married Rongorongo, the daughter of Toto (Sometimes called Nga-Toto). Turi did not sail for the newly discovered island at the time Kupe returned from his voyage, as is sometimes claimed; Turi was dwelling at Rangiatea, having fled from Hawaiki because he had committed adultery with Korahi, the wife of Taurangi-tahi. She was the elder sister of Moana-waiwai, the second wife of Tomo-whare. (This statement bears out what I learnt in Tahiti, with this difference, that Turi fled from Hitia’a on the east coast of Tahiti because of the jealousy of one of his wives; he went to Rai’atea.) Korahi was a wahine-kahurangi [or ariki], whose husband was Ao-marama.

Turi was followed to Rangiatea by those who wanted to kill him, but he fled. The reason, however, that he fled to this country (New Zealand) was the killing of Awe-potiki.

When Kupe and Turi met, the latter asked, “Where is the best part of the island according to what you saw?” Kupe replied, “The west coast. There is my karaka-huarua (i.e., the karaka-oturu, planted by Kupe). It is growing at the mouth of a river opening to the west, facing the southwest wind (uru o Tahu-makaka-nui). You will see a certain snow-clad mountain standing near the sea (Taranaki, or Mount Egmont). Direct your canoe to Tahu-para-wera-nui (to the south of this mountain) and you will see the best place to settle.”

Turi now said to his wife and said, “O Wife! If you had a canoe, we could go to this unoccupied land and make a home there.”

Rongorongo replied, “Who would want to live in a lonely place like that?”

But Turi did not cease to dwell on the idea of migration, constantly talking about it. At last Rongorongo spoke to her father Toto about it. Toto replied, “It is well; here is a canoe.” And so a canoe was given to Rongorongo to give to Turi. Toto said to Turi, “When you depart, and after you have arrived at Tiritiri-o-te-whenua on the ocean-if you find the land is bountiful, come back and fetch us all together with your brothers-in-law.” Turi consented.

Rongorongo was pregnant with her first born at that time. So Turi did not start for a long time, not until his three children were born-Turanga-i-mua, Taneroa and Tonga-potiki. When he was ready to go, Turi said to Kupe, “O Kupe! Let us both go to the land you have told us about.” But Kupe replied, “Kupe will not return.”

It must be clearly understood: Kupe and Turi did not meet at sea or anywhere else, but only at Rangiatea. The stories of other meetings are false [i.e., tahora, not told in the Whare-wananga].

Shortly after Kupe returned from Hawaiki to Rangiatea, Rongorongo’s first child was born, and Kupe said, “Let the name of the child be Turanga-i-mua; to signify my being the first to stand on Aotea-roa.” (Turanga, “standing”; i mua, “ahead”). Now for the first time the name Aotea-roa given by Kupe to the islands he discovered became known. Nga-Toto said, “O Turi! Let that also be a name for the canoe of our daughter.” Kupe said, “It is well,” and so the name “Aotea” was given to Rongorongo’s canoe, replacing the old one.

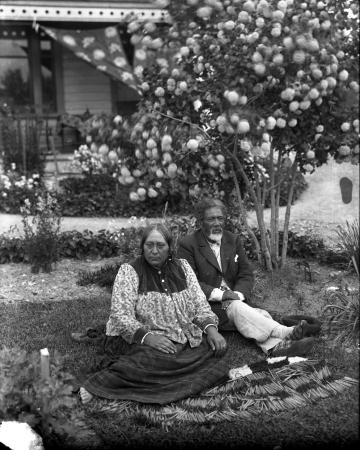

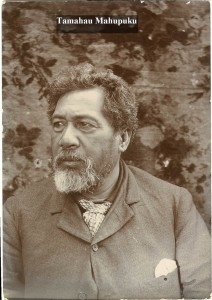

Mahupuku, Hamuera Tamahau

Mahupuku, Hamuera Tamahau

Little is known of Tamahau’s childhood or education. It is likely that he was baptised by William Colenso or William Ronaldson of the Church Missionary Society. He may have been self-educated, but could have been a pupil at St Thomas’s College at Papawai between 1860 and 1864. In the mid 1860s Tamahau was known as a rather wild young man who had worked for a time on Huangarua station. He was handsome, mixed much with Europeans, and for some years worked as a cattle drover. His brother was an ardent supporter of the Maori King movement, and, at least in the 1860s, Tamahau followed his lead.

Tamahau had three wives; the marriages were concurrent. His first wife, variously known as Wairata, Harete, Areta or Alice, was said to be the very beautiful part-Maori daughter of Jack Pain, an old whaler. His third wife, known as Clara, may have been of Nga Puhi. But Raukura, Tamahau’s second wife, had the most influence on his future. Her first husband was Matini Te Ore, and through this connection Tamahau gained influence at Papawai and was brought into contact with Te Manihera Te Rangi-taka-i-waho, who later appointed him his heir in matters to do with the people.

Tamahau had three wives; the marriages were concurrent. His first wife, variously known as Wairata, Harete, Areta or Alice, was said to be the very beautiful part-Maori daughter of Jack Pain, an old whaler. His third wife, known as Clara, may have been of Nga Puhi. But Raukura, Tamahau’s second wife, had the most influence on his future. Her first husband was Matini Te Ore, and through this connection Tamahau gained influence at Papawai and was brought into contact with Te Manihera Te Rangi-taka-i-waho, who later appointed him his heir in matters to do with the people.

This appointment was one foundation of Tamahau’s leading position at the growing Maori centre at Papawai; the other was the Mahupuku wealth. As members of one of the two leading families of Ngati Hikawera, Tamahau and Hikawera controlled a large part of the Nga-waka-a-Kupe block and had interests in several more. They leased land profitably and Hikawera developed his own sheep station. He fought attempts by Ngatuere Tawhirimatea Tawhao and Te Manihera to sell Nga-waka-a-Kupe. In the Native Land Court in 1890, and again in 1892, the judges upheld Ngati Hikawera’s claim to the block against the claims of Ngatuere and Ngati Kahukura-awhitia. Tamahau was heir to his brother’s wealth as well as his prestige on Hikawera’s death in 1891.

Tamahau had also worked as an assessor and agent in the Native Land Court. While claims to the Wairarapa lakes were being heard in 1882 and 1883 he acted for Hoani Te Toru. In introducing lists of potential owners Tamahau was working against Piripi Te Maari-o-te-rangi and Te Manihera, who wanted the hearing dismissed. He and Paraone Pahoro managed to persuade Raniera Te Iho-o-te-rangi and Piripi Te Maari of the benefits of registering the lake owners, who included Tamahau and Hikawera.

Two months after Te Manihera’s death in 1885, Tamahau was taking his place at important meetings, but shared the leadership at Papawai with Te Manihera’s half-brother, Hoani Te Rangi-taka-i-waho. He continued to develop the centre: a large house with an iron roof and stained glass windows was erected for visitors (and later replaced by the house, Hikurangi). Wooden houses were built with the proceeds of sales of totara from Mahupuku properties. A team of Ngati Porou carvers worked at Papawai during the 1880s, preparing the carvings for the great house Hikawera had planned. Eventually Hikawera presented them to Tamahau who erected the house, Takitimu, at Kehemane (Tablelands) early in the 1890s. Te Kooti attended its opening and predicted, perplexingly, that the wind would blow through it.

Perhaps Tamahau’s affluence accounts for his enthusiastic acceptance of all things Pakeha, and his support of various governments’ paternalistic plans for the Maori people. In 1891 he told the Native Land Laws Commission that he did not want Maori committees to be given the power to deal with Maori lands because he did not want the existing Wairarapa boundaries upset. He joined in the parliaments of the Kotahitanga movement from 1893, but refused to sign the deeds which set out the movement’s aims; he was suspicious of a clause which vested control of Maori land in the Kotahitanga government. In any Kotahitanga bills he consistently opposed wording which demanded separate powers. Henare Tomoana once snarled that Tamahau had argued about the same phrase for 10 days on end. Although he had still not signed the deeds, in 1895 he began to suggest that the parliament sit at Papawai.

Piripi Te Maari died on 26 August 1895. Within five months Tamahau had reached an agreement with the government for the sale of the Wairarapa lakes, which Piripi had always resisted. Tamahau requested continued Maori access to the lakes for fishing, and trusted the government to select suitable lands as compensation. (Cheap land in the King Country was eventually selected.) As a sign that all hostilities between the former Maori owners and the new settlers were at an end, he gave a grand picnic at Pigeon Bush. The politicians Richard Seddon and James Carroll and the settlers were welcomed with Tamahau’s finest oratory. Seddon emphasised that the lakes had not been sold but presented to the government; the £2,000 handed over as part of the deal was intended to cover the litigation expenses of the former owners.

Tamahau, principally responsible for ending the deadlock over the lakes, was afterwards regarded as a personal friend of Seddon. In 1897 Seddon, Lord Ranfurly (the governor) and other European notables accepted his invitation to the opening of the Aotea–Te Waipounamu complex built at Papawai for the Kotahitanga parliament. This was a T-shaped, partly two-storeyed building, including a dormitory, a dining room and a meeting hall with a raised dais for speakers. On this occasion Tamahau offered to the government the superlative carved house, Takitimu. He renewed his offer in 1898.

Tamahau was host to two sessions of the Kotahitanga parliament at Papawai in 1897, in April and October. During the sessions it was decided to inquire into the results of Te Keepa Te Rangihiwinui’s petition to the Queen that the five million remaining acres of Maori land should be reserved absolutely for Maori. Tamahau led the group which subsequently approached Seddon in Wellington. Seddon told them that the Queen considered Maori welfare to be the colonial government’s responsibility, and he was giving the matter his consideration. He suggested for the first time the setting up of Maori land boards.

Another 1897 project of Tamahau’s was the publication of the Maori-language newspaper Te Puke ki Hikurangi, edited by Purakau Maika. At first very much a vehicle to report the activities of the Kotahitanga movement, it soon expanded to include religious articles, advice on domestic matters for women, reports of foreign and local non-Maori news, and correspondence on canoe traditions and genealogy. One series of articles, to which Apirana Ngata contributed, was on Maori depopulation, its causes and remedies. In the newspaper’s pages Tamahau advertised for knowledgeable people to come to his hui to record Maori tradition and genealogy. This campaign led to the setting up of the Tane-nui-a-rangi committee, responsible for the preservation of much traditional material. This work, and publication of the newspaper itself, continued after Tamahau’s death. Te Puke ki Hikurangi was a major formative and educative influence on contemporary Maori.

Following his 1897 initiative, in 1898 Seddon drafted a bill ‘to provide for the Settlement and Administration of Native Lands’. The bill created a furore among Maori, mainly because of its paternalistic aspects. Tamahau set up a grand meeting at Papawai in May and June 1898 to discuss it. The meeting revealed a deep rift between Kotahitanga members in their attitudes: many rejected the bill outright, but a group of pro-government chiefs including Tamahau drew up a series of amendments, ensuring a Maori majority on the proposed Maori land boards and making other changes for greater local Maori control of land and social affairs. Many important Kotahitanga members rejected these amendments, since they had been adopted in defiance of the rules and regulations of the Kotahitanga parliament. In September Tamahau petitioned the government to adopt the bill with the Papawai amendments, but other petitions demanded that it be scrapped. When an inquiry was held by the Native Affairs Committee Tamahau expressed his faith and trust in the government, stating that Maori had never been disadvantaged by parliamentary legislation and that their grievances sprang from ignorance and improvidence.

Although nominally a member of Te Kotahitanga, Tamahau did not share its aim of self-determination. He was a member of a committee working outside the legislature to support Seddon’s 1900 Maori Lands Administration Act (which had eventually been passed as a result of the 1898 bill) and Maori Councils Act. These acts seemed in the early years of their administration to meet at least some Maori aspirations to local self-government and Maori-controlled reform. Their potential benefits were enthusiastically discussed in Te Puke ki Hikurangi, and the surviving leaders of Te Kotahitanga, beginning with Tamahau, praised for having achieved this result.

From 1894 to 1904 Tamahau was said to have spent more than £40,000 on various projects. These included his financial support of the Wairarapa Mounted Rifle Volunteers, a Maori company. In 1901 he offered to raise and finance a Maori force to fight in the South African war. The offer was refused by the British government, which had decided to use only white troops in the war.

At hui at Papawai and Kehemane, Tamahau was host to thousands. A brass band he supported played at these functions and accompanied him on his visits into town. One of his last projects was to erect a palisade to enclose the marae at Papawai. Totara logs were collected and after his death were carved into representations of important ancestors and erected facing into the marae, according to his wish, to symbolise peace. (Traditionally, carved figures faced outwards to threaten enemies.)

Tamahau died at Papawai on 14 January 1904. He left no children but had adopted Aketu Piripi, who died at the age of 17. An Anglican service was conducted in Maori, and the body was taken for burial at Kehemane, followed by a large crowd. His mourners included Seddon and Carroll. By contemporary Europeans Tamahau was regarded as one of the most ‘progressive’ of Maori. To the large Maori community at Papawai he was father and leader.

After his death the glory of Papawai as the rendezvous of two governments – of the colony and of Te Kotahitanga – faded. No one replaced him, and few could afford to finance the huge gatherings of the past. Many felt that the Maori councils, whose setting up he had supported, would make such leaders redundant. Aotea–Te Waipounamu blew down in a storm in 1934, and a marble monument to Tamahau’s memory, unveiled at Papawai in 1911, was damaged by earthquake in 1942. The totara palisades gradually collapsed, and at Kehemane on 31 December 1911 Takitimu burned to the ground. As Te Kooti had predicted at its opening, now only the wind blew through the site.

Maika, Purakau

Purakau Maika was the son of Maika Purakau, a pro-King movement chief of Hurunuiorangi pa at the junction of the Tauheru and Ruamahanga rivers. His father was of Ngati Hikarahui hapu, which combined lines of descent from Ngati Kahungunu, Te Aitanga-a-Whata, Rangitane and Ngai Tahu of southern Hawke’s Bay and Wairarapa. Maika Purakau was the elder brother of Kaipaoe III, the mother of the half-brothers Hoani Paraone Tunuiarangi and Taiawhio Te Tau. Purakau Maika’s mother was Makuhea, also known as Hoana, a daughter of Poihipi and Taukuta of Ngati Tangatakau. Purakau Maika was also of Ngati Rakairangi.

Purukau Maika’s date of birth is likely to have been before 1870. He had at least two sisters, Hiria and Pane. No details of his upbringing and education are recorded, save that he did not attend secondary school. He was married to Terina Purakau Maika.

Although a man of rank and connections, Purakau Maika held no great authority in Wairarapa in his early life. In 1891, with other Ngati Rakairangi chiefs, including Piripi Te Maari-o-te-rangi and Tunuiarangi, he was listed as owning a part of the Wairarapa lakes. In 1894 he became associated with Tamahau Mahupuku’s grand and successful plan to bring Te Kotahitanga, the movement for a separate Maori parliament, to Papawai. Purakau was in overall charge of a group of young men, 32 of whom were training to play in Tamahau’s band, while another group of 10 were being trained as carpenters to erect the buildings and accommodation needed for the Kotahitanga parliament. Purakau was their elder, responsible for their general welfare.

Tamahau Mahupuku also conceived the idea of a Wairarapa Maori newspaper to be the vehicle of Te Kotahitanga. The idea was presented in 1894 to the parliamentary session of Te Kotahitanga at Pakirikiri, near Gisborne, by Tunuiarangi, Te Whatahoro Jury and Te Teira Tiakitai. Little but verbal support resulted, and the Wairarapa leaders realised they would have to achieve their ambition on their own. In 1895 Te Whatahoro took Kiingi Tuahine Mate Rangi-taka-i-waho, who had been educated at Te Aute College, to Wellington and found him work with an English-language newspaper. Despite falling ill, Kiingi worked there for nearly six months, and when the Wairarapa leaders bought a printing press in Wellington in 1896, he had sufficient skills to teach others. The press was set up at Papawai, and Purakau Maika was put in charge of the young men training to be its staff.

When their training was complete, Purakau Maika moved his staff and the printing press to a site near the Greytown North Post Office. The first issue of Te Puke ki Hikurangi was published on 21 December 1897. Purakau Maika was its editor, heading a team of seven: Kiingi Rangi-taka-i-waho was sub-editor and translator; Tawhiro Renata, who was to stay with the paper until 1906, was foreman; and there was a manager, three compositors and a mechanic, dignified with the title of chief engineer. All worked without wages; the money from subscriptions paid for paper, dies and machine maintenance.

For the first three years Purakau played a prominent role as editor. His name studded every edition as correspondents addressed him personally through the paper’s columns, and replies were signed with his name. Purakau probably did a fair amount of his own reporting; accounts of hui and tangihanga read as though he himself were present. The first issues of the paper showed the lack of expertise of its staff in layout and composition, but as time went on they gained in professionalism. The issues of 1898 were devoted entirely to the Kotahitanga parliament, which Purakau attended. He printed an English version of its amendments to Premier Richard Seddon’s proposed 1898 native lands legislation.

After the 1898 session the printing press and the staff of Te Puke ki Hikurangi were brought back to Papawai marae, and kept more closely under the control of Tamahau Mahupuku. From October 1898 the paper was published by Tawhiro Renata. A change of editorial policy became apparent from 1899: Purakau Maika no longer signed letters personally, correspondence was addressed to and answered by ‘the editor’ or ‘Te Puke’, and his name disappeared from the paper’s official address. No issues were published in 1900, and it is not known if Purakau continued to edit the paper between 1901 and 1906. At least some articles signed ‘Te Puke ki Hikurangi’ during this period were written by Tamahau’s niece, Niniwa-i-te-rangi, effectively the paper’s proprietor for two years after Tamahau Mahupuku’s death in 1904.

From 1906 Te Puke ki Hikurangi ceased publication until July 1911 when it was resurrected. This time Purakau Maika was firmly in the saddle, although he published a photo of Tamahau Mahupuku, his mentor, in every issue from 16 October. The paper was printed and published by H. Tuhoukairangi, one of Purakau’s young kinsmen, at their registered office in Carterton; Purakau was the proprietor and editor. Although he asked correspondents to address their letters for publication to him personally, after the first issue he adopted the convention of the anonymous editor.

The paper provided a picture of the political and religious life of Maori, not only in Wairarapa but also nationally, available in few other sources. Six months after the revival of Te Puke ki Hikurangi, Purakau, together with James Carroll, Te Whatahoro Jury, his younger brother Taare (Charles) Jury and Iraia Te Whaiti, became a director of the company producing Te Mareikura, another Wairarapa Maori-language newspaper. Edited by Whenua H. Manihera, its first issue had appeared in August 1911. Although Purakau assured his readers that he had not abandoned Te Puke ki Hikurangi, two competing newspapers were too much for the market. Both papers failed in 1913, the older paper surviving the newcomer by six months.

Outside his newspaper activities, Purakau had been gaining prominence as a Wairarapa leader. During the 1897 session of the Kotahitanga parliament at Papawai he was elected to a committee of seven chosen to discuss issues raised by Hone Heke Ngapua, MHR for Northern Maori. He was also present during the 1898 session and took part in a lengthy debate with Paratene Ngata over the question of Maori mana as affected by native land legislation. Between 1 and 9 April 1898 Purakau organised one of a series of annual hui between the different Christian sects sponsored by the Mormon church. Anglicans, Catholics, Mormons and Ringatu met together at a Wairarapa Mormon church. They were visited by Hirini Whaanga and seven missionaries from Utah, USA. In July 1899 Purakau was chosen to escort the young Apirana Ngata around Wairarapa, on his mission as travelling secretary of the Te Aute College Students’ Association.

Purakau was on the committee of the Wairarapa Mounted Rifle Volunteers, and in 1902 he was secretary of Wi Pere’s electoral campaign in Wairarapa. In 1903 he was appointed by the Rongokako Maori Council to the post of chairman of the Hurunuiorangi marae committee. Occasionally he represented Wairarapa at Maori events in other parts of the country, and his name appeared in lists of invited guests at many hui and tangihanga.

It is probable that Purukau’s influence waned after the failure of the newspapers. At least from 1912 he was a member of the Rongokako Maori Council and the Tane-nui-a-rangi Committee, responsible for the organisation of hui whakapapa (grand meetings to discuss and record genealogies). One was held at his home marae, Te Puanani, in Carterton, in 1913. But his name fades from the public record. He was last mentioned in Te Kopara, another Maori newspaper, in 1917, as one of the Wairarapa leaders inviting guests to Te Puanani to the opening of the house, Nukutaimemeha, which was to take place in March 1918. The date and place of his death have not been found, but Terina died at Gladstone on 14 May 1944. At that time there were no surviving children.

Matangi came from the Wairarapa

Matangi was a Rangitaane chief who lived in the Wairarapa. Sometimes relations came to visit him from the other side of the Tararua Mountains. These people had mouthwatering stories of great flocks of birds that were so plentiful they were very easy to catch.

Impressed by what he heard Matangi set out to find this great feathered treasure. Not long after he left the Wairarapa a shadow cast itself over him together with the din made by thousands of wings, he had found his prize. He continued on following the birds naming many places along the way. The land that he walked through had so impressed him that he built a village when he reached the sea.

When word got back to the Wairarapa that Matangi was going to stay on the west coast, people from his old home decided to call on him. After receiving messages to expect company Matangi was disappointed to find that no one came.

In time Matangi discovered the reason for his sadness was a taniwha. This creature lived in a lake near the present village of Rangiotu by the Manawatu River. Any unsuspecting person that happened to get to close to the lakeside was devoured by the ravenous creature within.

Determined to rid himself of the taniwha Matangi came up with a simple plan. He ordered a strong snare made of flax to be placed on the shore of the lake. With the trap set Matangi and a group of his men drew the monster out from the depths. They made such a noise that the taniwha rushed at them straight into the waiting flax loop. And so the life of the murderous taniwha was quickly ended.

Since the day that the taniwha was slain, the beach where Matangi built his village became known as Himatangi, which means “the place where Matangi went fishing”.

Matirie

Castlepoint Lighthouse

Matua

Old Lansdowne School