Music

There is music in nature.

Think of bird song or the sound of wind whistling through a valley, even the constant noise of cicadas at the height of summer or waves crashing on a beach.

Then there is music made by humans by voice or instrument.

The whakapapa of the atua is shared in ancient waiata. The stories of how species came to be is found in waiata.

Spoken oriori can be about a range of subjects but are often used to pass on information about history or nature. Stories like the meaning of Whakaoriori show us how useful information was passed from grandparents to grandchildren about the atua while being surrounded by the atua.

Some forms of waiata tell stories about the deeds and feats of famous ancestors who are likened to mighty trees and other symbols of strength.

Taonga puoro, traditional Instruments are mokopuna of the atua and have a whakapapa or family of their own.

The word for tune is Rangi. Melodic instruments such as flutes and trumpets were part of his family. Rhythmic instruments such as anything struck belonged to Papatūānuku. These could be stone, bone or wood. Poi and spinning disks also belonged to Papatūānuku. Shell instruments like putatara came under Tangaroa.

Nanakia lived on Tararua maunga

Nanakia who was sometimes called Ngahakea is a taniwha who lives on Tararua Maunga up where the Hector River begins. Sometimes he used to make himself look just like a man so that he could go down to the Wairarapa valley and move among people. Once down on the plains Nanakia used to steal away with people into the night taking them back to his home in the mountains.

Patupaiarehe, the fairy folk also dwell up on Tararua. Fair skinned with long tasselled hair and eyes that shine like glowing embers the patupaiarehe are the descendents of a hapu that was banished from the valley. Over time the stature of our fairies has become shorter than normal humans with their nature turning to mischievous pranks and malicious assaults.

The patupaiarehe live in the tops of trees that are engulfed within the strangling embrace of rata. The encircling vines of the rata provide a ready made staircase. Although they seem to have given up the practice, in the past they would sneak down to villages on the plains. If they did not walk they would float down on vessels made of raupo stalks. Like Nanakia they were known to carry away children, preserved food, animals and occasionally wives!

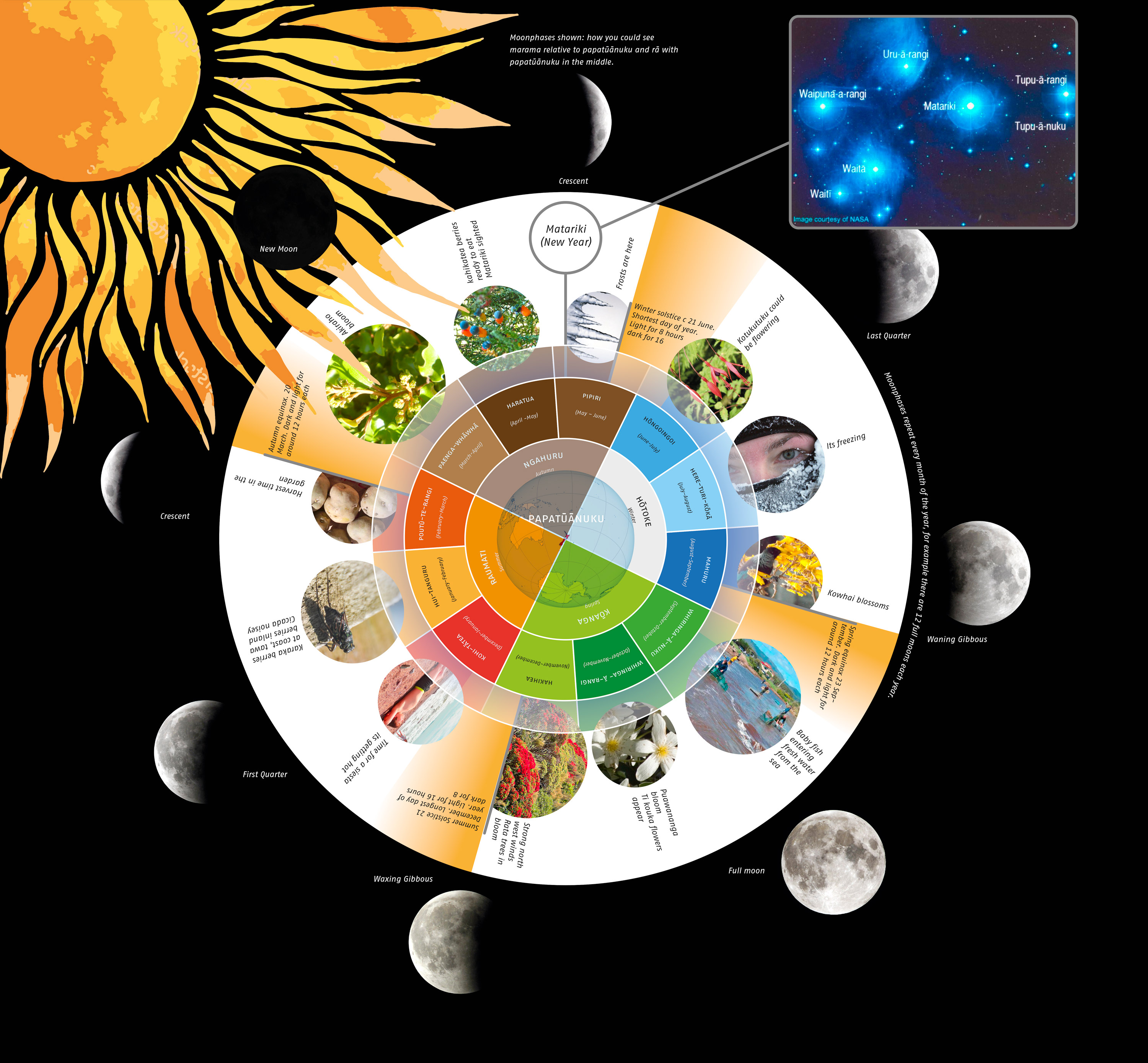

Ngā maramataka

Lunar Calendar (ngā maramataka o te tau)

Download PDF for print

Marama controls the tides which in turn tells us when it is the best time to do certain activities.

For example gathering food from the rocks and rocky shore studies are best done at low tide, while observing fish entering into streams is best on the incoming tide.

The cycles of the moon are the basis for the annual calendar.

Nga Whakamaramatanga o te Moana – Voices from the coast

These personal reflections were gathered as part of an investigation into marine protection on the Wairarapa Coast by the Department of Conservation in association with Rangitaane o Wairarapa and Ngati Kahungunu ki Wairarapa. The investigation, due for completion in late 2003, revealed a startling lack of historical literature on our coast. To fill the gap in our knowledge and to help us form marine protection strategies for the future, we asked six kaumatua to tell us of their relationship with the coast, and share their memories of specific locations between Akitio and Palliser. Their collective memory now forms an important body of work for us to reflect on now, and in the future.

Ngai Tumapuhia-A-Rangi

“Kia hokowhitu Tumapuhia,

putiki makawe tahi,

heru tu rae anake”.

After Tumapuhia had established his mana/prestige in the Wairarapa other hapu/tribes attempted to conquer the Tumapuhia-A-Rangi hapu to gain control of the seacoast. Ngaokoiterangi, who had been living among Ngati Ira, stated that he would return to the Kaihoata river valley saying, “It is a valley filled only with rangatira/chiefs, whom are adorned with the chiefly symbols of a single topknot and a comb on the forehead.”

During this period of turmoil Ngaokoiterangi was killed and the descendants of Tumapuhia gathered at Waikekeno and fought to the death against insurmountable odds. When all the other hapu from the Wairarapa observed the dress of the bodies of the dead, remarks were made with regard to the chiefly status of the dead, and the words of Ngaokoiterangi were remembered and enshrined in the tribal whankatauki or tribal saying:

“Kia hokowhitu Tumapuhia, putiki makawe tahi, heru tu rae anake”.

[“The warriors of Tumapuhia, they are all adorned with the single topknot and the comb on the forehead”]

After this battle called “Ahuriri” Hikarara, who had observed the events sought assistance from relatives further up the coast. A war party was raised with assistance from Ngati Porou and Ngati Kahungunu hapu living on the coast and four subsequent battles were fought in the Wairarapa, around to Wairarapa Moana or Lake Wairarapa.

This is how Ngai Tumapuhia finally established and consolidated their mana in the Wairarapa. In spite of fraudulent transactions by the Government and the devastating effects of British colonisation the Kaihoata Valley remains the spiritual mauri or essence of the hapu.

The “Pou” or guardian rangatira/chief of the Kaihoata in the turbulent period of the 1800s was Rongomaiaia Te Waaka or Tamakiuruhau. It is from his children and descendants that the land for a marae or ceremonial meeting place was gifted, and the present day Ngai Tumapuhiaarangi Marae Committee was established.

Ngake and Whātaitai the taniwha of Wellington harbour

Once long ago, before the time of Kupe, when Te Ika-a-Māui was just fished from the depths of the ocean, there lived two taniwha, Ngake and Whātaitai.

In those times, Wellington Harbour, Te Whanganui-a-Tara, was a lake cut off from the sea, and abundant in fresh water fish and native bird life. Ngake and Whātaitai lived here in the lake at the head of the fish of Māui (Te Ika-a-Māui).

Ngake and Whātaitai had a great life in their special lake, with all the time in the world to do as they pleased. Ngake was a taniwha with lots of energy. He liked to race around the shores, chasing fish and eels and leaping after birds that came too close. Whātaitai was the opposite, he preferred to laze on the lake’s shores, sunbathing and dreaming taniwha dreams.

When Ngake and Whātaitai were close to the south side of the lake, where the cliffs came down to the waters edge, they could hear the crashing waves of the ocean falling on the shores nearby so when sea birds flew overhead, Ngake and Whātaitai often yelled to them, “Tell us, sea birds, what is so special about the sea?”

And the birds would always reply, “The sea is deep, it’s vast, it’s wide, it’s where many different fishes hide. The sea is the home of Tangaroa, of Hinemoana and many others.”

Whātaitai and Ngake could only imagine what secrets the sea held. Whātaitai would loll on his back in the middle of the lake dreaming, imitating the sea noises in his throat. Ngake would swish his tail furiously, making huge waves that crashed against the lake’s shore.

As the years went by the two taniwha grew bigger, and the boundaries of their lake seemed to grow smaller.

Ngake was adamant he had outgrown his home and soon convinced Whātaitai that they both needed to break free from the lake that imprisoned them.

One summer morning when Whātaitai was enjoying the morning sunshine at the north end of the lake, Ngake began circling around at high speeds yelling, “Today is the day that I will break free of this lake and swim in the endless sea!”

Whātaitai began to be excited at Ngake’s suggestion.

Ngake crossed to the north side of the lake and coiled his tail into a huge spring shape. He focused his sights on the cliffs to the south and suddenly let his tail go. With a mighty roar Ngake was thrust across the lake up over the shore and smashed into the cliff face.

Ngake hit the cliffs with such force that he shattered them into huge hunks of rock and earth, effectively creating a pathway through to Te Moana o Raukawa (Cook Strait). Ngake, cut and bruised, slipped into the sea, finally free to explore as he had dreamed.

Whātaitai was shocked at the devastation that Ngake had caused, but also glad that his brother had safely made it to the other side. Whātaitai knew he would have to follow.

Whātaitai retreated from the north side of the lake to wind his tail into a spring as he had seen his brother do. He said a prayer to the taniwha gods, then let his tail go. But Whātaitai hadn’t been very active in the past, and he wasn’t as strong or as fit as Ngake, so his take-off was much slower than his brother’s.

As Whātaitai entered the gap forged by Ngake he didn’t realise the tide was out. His stomach dragged on the ground, eventually slowing him to a stop. Whātaitai was stranded, stuck between the sea and the lake, desperately lashing his tail and trying to move, but to no avail.

Whātaitai could do nothing but lie there hoping that the incoming tide would lift him high enough to carry him across to the other side. But when the tide finally came in, it only helped to dampen his scaly skin and provide fish to sustain his hunger. Whātaitai was stuck without a hope of ever moving.

As the years passed Whātaitai became accustomed to his life stranded between the lake and the open sea. The tides would come and go providing him with food and keeping his skin healthy and moist. Whātaitai made many friends with birds and sea creatures, and these companions helped him deal with his fate.

One morning there was a dreadful shudder beneath the ocean floor. A huge earthquake erupted. Whātaitai was lifted out of the shallow water and high above sea level. Whātaitai could do nothing, he was stranded high above the water and he knew his life would end. Whātaitai bade farewell to his many bird friends and animals and soon after gasped his final breath.

As he died, Whātaitai’s spirit transformed into a bird, Te Keo, and flew to the closest mountain, Matairangi (Mount Victoria). Te Keo looked down on the huge taniwha body that stretched across the raised sea bed and cried. She cried for the great friendships Whātaitai had made, shown by the huge numbers of birds and sea life that had gathered around, and for the freedom of the sea which Whātaitai would never experience. When Te Keo had completed her lament, she bade farewell to Whātaitai, then set off to the taniwha spirit world.

Over the years Whātaitai’s body turned to stone, earth and rock and is known to this day as Haitaitai. Matairangi still looks down on the body of Whātaitai and the very top of Matairangi is still known as Tangi te Keo.

When Ngake let the spring in his tail loose he used so much force that he created a great gash in the earth and a river was formed. This river is now called Teawakairangi or the Hutt River.

The remnants of rock smashed aside when Ngake exited into the sea are visible today and Te Aroaro o Kupe (Steeple Rock) and Te Tangihanga o Kupe (Barrett’s Reef) have long been known as dangerous rock formations to mariners entering the Wellington harbour.

Although Ngake was never seen again it is still believed that he resides in the turbulent waters of the Te Moana o Raukawa (Cook Strait). When the sea is calm Ngake is off exploring Te Moana Nui a Kiwa (the Pacific Ocean). When the sea is turbulent and rough, Ngake is at home chasing sea life to satisfy his taniwha appetite.

And this is the story of Ngake and Whātaitai, the taniwha of the Wellington harbour.

Ngarara Huarau Graphic Novel

View ListingNgarara Huarau lies beneath Uwhiroa

This is the story of a taniwha called Ngarara Huarau who was also called Mokonui. The story happened near the Ruamahanga River in the Gladstone area, southeast of Masterton.

Ngarara Huarau was a huge lizard that originally lived in a cave at a place called Marokotia which is in the Pacific Ocean. He became fed up with his life and decided to visit his sister who lived in the Wairarapa valley. As he was leaving some of his scales rubbed on the rough edges of his cave and it is said that these became Tuatara.

So he ventured across Te Moana nui a kiwa in search of his sister Parakawhiti. When he knew he was close he turned up the Pahaoa River and followed it until he reached the Wainuioru River. He then turned into the Marumaru stream until he reached a place called Mauri-oho where upon he jumped to the top of the Maungaraki Mountain.

Feeling weary Ngarara Huarau found a place to hide from which he could satisfy his mighty appetite. Unfortunately for the local Ngai Tara people the taniwha craved for human flesh. Many vicious and fatal attacks occurred thereafter with the place being called Hautua-pukurau o Ngarara Huarau. Once his appetite was satisfied the taniwha moved down to Te Ana o Parakawhiti, The cave of his sister Parakawhiti.

By now the people living within the vicinity of the deaths were aware of the cause of their losses and determined to rid themselves of the vile creature. While they tried to offer the taniwha gifts their efforts were to no avail. Instead more and more people went missing.

The people employed a famous warrior named Tupurupuru to destroy the taniwha. Tupurupuru and a handpicked group of aids soon worked out that Ngarara Huarau had made himself a lair above the Kourarau stream. Upon inspection the track to the lair was found to be narrow and lined with kahikatea trees. It was time to employ a plan that would rid the people of the monster.

At the cost of a number of unfortunate warriors the trees bordering the track to the taniwha lair were cut almost through. This took some time but when the trap was set the plan was put into action. Tupurupuru sat observing the movements of Ngarara Huarau until one day the taniwha returned to his home tired from a days plundering of villages down on the flats by the Ruamahanga River. Once he was sure that the creature was fast asleep inside his lair Tupurupuru moved stealthily up to the entrance and there tethered his dog.

The brave man had immediately turned and ran as fast as he could back down the track. Upon seeing its master leave the dog raised a din that awoke the monster from a deep sleep. This disturbance incensed the taniwha so that he rose to destroy the source of the noise. As the dog was only loosely tied it broke free and ran off in the same direction as its master, with the taniwha closely behind. The monsters massive tail twitched like an angry cat swaying to and fro as he thundered down the valley. In the process the huge kahikatea began to topple all around the monster so that the great weight of many trees crushed Ngarara Huarau. While he was not immediately killed his injuries were grievous. This provided Tupurupuru and his men with the chance to chase the mortally wounded creature to the Uwhiroa swamp where he became stuck in the soft ground. Eventually he sank below the surface, breathing his last breath in the process. The remains of Ngarara Huarau the villainous taniwha lie beneath Uwhiroa to this day.

Where are some of the places mentioned in this story

Marokotia Is also referred to as a place in the Hawkes Bay

Maungaraki maunga the hills that rise to the east of Gladstone

Kourarau The Kourarau dam at the top of the first rise on the Gladstone Te Wharau Road is a well known landmark. Another version of the Ngarara Haurau story says that the cliffs near Kourarau are the bones of the taniwha

Te Ana o Parakawhiti The cliffs that can be seen south east of the Gladstone Inn or Hurunuiorangi Marae.

Uwhiroa swamp the land on the southwest corner of Longbush and Millers Road, Longbush.

Tupurupuru The land where the surge tower is on the first rise of the Gladstone Te Wharau Road as you turn left from the Masterton Gladstone Road.

Ngarara Huarau taniwha

Long ago a giant taniwha named Ngarara Huarau lived in a cave under the ground at Makorotai on the Heretaunga Plains (Hawke Bay). His family had all left, or died, and he was by himself. He was lonely and tired of living by himself in a cave so he decided to visit his sister Parikawhiti who lived in the Wairarapa.

With a great roar he came out of his cave and, with his mighty talons, split the land open leaving a huge chasm. In doing this some of his scales fell off and became Tuatara Lizards.

Setting out for the ocean he burst the land open and cut a big channel. This channel and the chasm filled with water and became the Tiraumea River.

Arriving at the great ocean of Kiwa he began his journey south to the Wairarapa. On his way he stopped at every river, lifting his head up high and sniffing to see if he could smell his sister. On arriving at the mouth of the Pahaoa River he became very tired and decided to rest there for a while.

He continued his journey south and swam up the Pahaoa River, into the Wainuioru River and finally the Marumaru stream. When he reached the far side of the Maungaraki hills behind Gladstone he was stopped by a very high steep hill. By this time he could smell his sister and knew she was near. He was very excited. He tried to jump to the top of the hill, but he kept slipping back. He tried again and again. At last he managed to get his feet on a ledge and jumped to the top leaving the marks of his footprints at a place called Hautua Pukurau o Ngarara Huarau.

He rested for a long time at the top. He could smell humans down in the valley below and hid himself from them. Later, he moved on down into the Kourarau Valley where he made a lair among the Kahikatea trees. From there he finally reached sister Parikawhiti, who lived in a cave in the side of the hill at a place near the present Gladstone Hotel. This place is named Te Ana o Parikawhiti.

Ngararau Huarau was happy to see his sister and decided to make a new lair in the Kourarau Valley where, soon after, he terrorised the local people. He caught and devoured any unsuspecting person who passed near. He also raided further affield. It became obvious to the people there that they would have to kill the taniwha before he devoured them all.

A young warrior called Tupurupuru, who lived in a nearby pa took it upon himself to kill this beast by setting a trap. Along with three of his friends he worked out a plan to take the taniwha by surprise.

Working quietly, while the taniwha was asleep, the men partly cut through the huge kahikatea trees around his lair. Then Tupurupuru crept up to the entrance and loosely tied a dog to a tree. As he crept away the dog began to bark and soon Ngarara Huarau appeared from inside his lair. With a great roar he rushed out of his lair thrashing his tail about. The dog broke free and ran through the trees where Tupurupuru and is friends were waiting. Ngarara Huarau was very angry and began to chase after the dog – roaring and thrashing his tail about. As the beast neared the trap his thrashing tail brought the partly cut trees crashing down on top, hurting him so badly that he was weakened by the injuries. The warriors immediately rushed up and began to kill the taniwha with their spears and clubs.

Ngarara Huarau managed to survive the brutal attack only to be driven into the swamp at Uwhiroa where he later drowned.

Ngāti Hāmua and Kai Resource (Kai kit)

The Ngati Hamua and kai book has been produced to introduce all people to the kinds of food our ancestors ate for hundreds of years. Well most of them because some have arrived in the last 200 years.

All of the foods are still available locally and with the exception of endangered wildlife and poisonous berries can be gathered and sampled according to seasonal availability. Some of the food is a bit smelly or could taste a bit funny but most is good for you. There are a few that have quite a lot of sugar but they are very yummy. If you are a kid take an adult out and look around for the trees, plants, birds and fish. You don’t have to hurt anything just see if you can spot them.

Only a selection of foods have been highlighted in this book, many others were used, especially when more variety became available with the arrival of people from different lands. Yet one way or another some of our people have continued to enjoy both the foods that were once abundant naturally and those that have become common place through introduction.

A simple google search on the internet can provide more informa-tion and recipes. Just try typing in a key word such as Manuka and numerous sites with information on this tree will come up.

Please give the foods a go, although it is even satisfying to observe when different native plants and trees yield best so that you can their bounty.

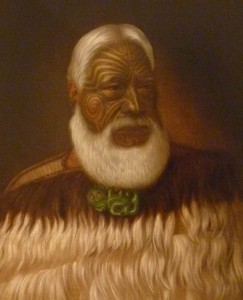

Ngatuere Tawhirimatea Tawhao

Ngatuere gave an account to the Native Land Court of the migration of Ngati Kahukura-awhitia from Heretaunga (Hawke’s Bay) to Wairarapa. Three brothers, one of them Pouri from whom Ngatuere was descended, brought Te Rangitawhanga, a great-grandson of the ancestor Kahukura-awhitia, to his mother’s relatives in Wairarapa. Pouri negotiated with Te Rerewa, Te Rangitawhanga’s uncle, the right to occupy land in exchange for carved canoes. The land included the district where Ngatuere was born, near present day Greytown. Ngati Kahukura-awhitia gradually cleared the forest, until in the time of Tawhirimatea, father of Ngatuere, it had become an open plain.

Little is recorded of the early life of Ngatuere, except the various places where his people lived while he was a youth. By the 1820s, when the northern peoples who had migrated to the Cook Strait coast invaded the Wairarapa region, he was already a major tribal leader. His people were driven from their homes by a war expedition led by Mananui Te Heuheu Tukino II of Ngati Tuwharetoa. His wife’s father was carried off at the battle of Tauwharenikau (Tauherenikau); later, one of Ngatuere’s elder brothers was killed at Te Waihinga by Ngati Toa. Ngatuere was one of the chiefs who escaped after the defeat at Pehikatea about 1834. After this event most of the people of Wairarapa, including Ngatuere, took refuge at Nukutaurua on the Mahia peninsula. Before the flight north, Ngatuere said, ‘they constantly fled from place to place in fear’.

Little is recorded of the early life of Ngatuere, except the various places where his people lived while he was a youth. By the 1820s, when the northern peoples who had migrated to the Cook Strait coast invaded the Wairarapa region, he was already a major tribal leader. His people were driven from their homes by a war expedition led by Mananui Te Heuheu Tukino II of Ngati Tuwharetoa. His wife’s father was carried off at the battle of Tauwharenikau (Tauherenikau); later, one of Ngatuere’s elder brothers was killed at Te Waihinga by Ngati Toa. Ngatuere was one of the chiefs who escaped after the defeat at Pehikatea about 1834. After this event most of the people of Wairarapa, including Ngatuere, took refuge at Nukutaurua on the Mahia peninsula. Before the flight north, Ngatuere said, ‘they constantly fled from place to place in fear’.

They were away about eight years, and then returned after negotiations with Te Wharepouri of Te Ati Awa. At first the Wairarapa people stayed together for mutual protection. Then, as their confidence grew, they began to reoccupy their former lands. Ngatuere and his people went back to the area around Te Ahikouka and Papawai. At this time Pakeha settlement of Wairarapa was just beginning. The region was being explored by surveyors of the New Zealand Company and settlers were looking for land to graze their sheep.

In this situation Ngatuere responded vigorously to challenges to his authority as a person of mana. These challenges came from younger men, more experienced in dealing with Pakeha, such as Te Manihera Te Rangi-taka-i-waho and Raniera Te Iho-o-te-rangi; from the agents of the Crown; and from the missionary William Colenso, who seems to have deliberately affronted his mana. In 1846 Ngatuere received Colenso with kindness at his new pa, Otaraia, on a bend in the Ruamahanga River, just above Lake Wairarapa, but the missionary’s arrogant nature and tone of moral superiority soon led to bitter quarrels.

In 1847 a road was being built from the Hutt Valley north to the place where the town of Featherston would be founded. Colenso feared that his converts in the district, which was part of his ‘parish’, would suffer evil results from working on the road, that they would work on Sundays, and be exposed to the temptations of alcohol and prostitution.

Ngatuere had quarrelled violently with the Pakeha roadworkers and withdrawn his people from the work. But he took the chance to damage Colenso’s reputation by spreading the story that the missionary had warned him that the road would be used by the military to destroy the Maori. William Williams, the East Coast missionary, considered that Ngatuere had tried to discredit Colenso because he had objected to Ngatuere’s allowing a young girl to co-habit with one of the roadworkers.

The relationship between Ngatuere and Colenso grew worse. He refused to go near Colenso’s tent at Kaikokirikiri, north of Masterton, unless a tohunga, whom Ngatuere believed to have killed his daughter, Ani Kanara Maitu, by witchcraft, was sent away. He and his brother Ngairo made Colenso’s work difficult by encouraging horse-racing at Kopuaranga and allowing the young men to drink spirits. At the marriage of Hemi Te Miha, when both men were present, Colenso grossly insulted Ngatuere and Ngairo by tossing aside their gift of tobacco. Smoking, for Colenso, was another moral evil. The enraged Ngatuere vowed he would never allow a Christian minister to settle in his district.

Ngatuere’s frequent rages and acts of violence earned him an unfavourable reputation among settlers who were, however, happy enough to accept his protection when they needed it. W. B. D. Mantell described him as a bully. However, a man of his time and standing would have been under a severe strain in coping with the coming of colonisation. And in fact he did respond positively to those changes, even though an old man. He learned to write fluently in Maori and was capable of dealing shrewdly with Europeans over land matters. He consistently opposed the agents of the Crown who were seeking to buy land, and was able to hold on to his own interests when others were losing theirs. While others failed to protect themselves, he was able to prevent the settler B. P. Perry from occupying a section of the Taratahi block, and to remove C. B. Borlase from his Waihakeke run.

In his later life he was constantly at odds with Te Manihera Te Rangi-taka-i-waho. These clashes began in 1848 when some junior chiefs forged the signatures of Ngatuere and other senior chiefs on a deed purporting to sell the Tauwharenikau block to the Crown. Then in 1852 Te Manihera added insult to injury by allowing his horse to beat those of Ngatuere and Ngairo at the Kopuaranga races. There were differences, too, over land sales, and over the establishment at Papawai of a missionary centre, college and Maori township. The Papawai flour mill, built by the government, became the source of bad feeling between the two chiefs. Te Manihera, determined to be the main patron of Papawai, did all he could to prevent Ngatuere and his people from using the mill. By 1868 Ngatuere had withdrawn his people from Papawai altogether.

The Wairarapa runanga, established in 1859, was also a source of dispute between Ngatuere and Te Manihera. Ngatuere’s brother, Ngairo, had been one of its founders, but Te Manihera was soon seen as its leader. In 1860 a ‘fearful row’ broke out between Ngatuere and some Ngai Tahu over the ownership of the Hurunuiorangi reserve. Te Manihera and the runanga supported the Ngai Tahu claim, while Ngatuere turned to the government for support.

Ngatuere was not wholly opposed to the runanga, or to the King movement and the Pai Marire religion. His brother was deeply involved in all three, and the two seem generally to have been in agreement. He promptly accepted the invitation to attend the Kohimarama conference of 1860, and this induced other chiefs to go, including Te Manihera. In the war that followed Ngatuere kept Wairarapa from becoming another theatre of war. Though there were plenty of land disputes with the government, Ngatuere refused to allow local people, in association with a Hauhau faction, to attack settlers. He took up a pro-government position in order to protect his own and his people’s interests.

A Wairarapa tradition tells that Ngatuere went to meet an approaching, hostile war party, either King movement or Hauhau, in the mid 1860s. He met them 10 miles north of Masterton, and so great were their numbers, his mouth dropped open in surprise. The place came to have the name Mikimikitanga-o-te-mata-o-Ngatuere-Tawhirimatea-Tawhao (surprise on the face of Ngatuere Tawhirimatea Tawhao). It was later shortened to Mikimiki, but a road sign bearing the full name, one of the longest in New Zealand, was erected in 1975. A further tradition records that at the spot where Ngatuere and other chiefs met Governor George Grey to discuss the keeping of peace in Wairarapa, a huge totara post was erected and named after Ngatuere, ‘Poroua Tawhao’.

Although an Anglican clergyman, the Reverend Pineaha Te Mahau-ariki, officiated at his burial, Ngatuere may never have become a Christian. At Native Land Court hearings (with only one late exception) he did not swear on the Bible, but gave an affirmation. He had more than one wife: Te Mapu, the sister of Te Matorohanga, the tohunga and sage, whose knowledge was recorded by Hoani Te Whatahoro Jury; Mere Makarini; and Ani Patene.

Although he was considered ‘loyal’, and was at one time appointed an assessor for the Native Land Court, he was too independent and autocratic to be appreciated by Europeans. But to his own people he was the embodiment of mana and tapu. He died on 29 November 1890 and was buried near Waiohine, not far from his place of birth. He was survived by four daughters and three sons, of whom two are known: a son, Kingi Ngatuere, and a daughter, Akenehi Ngatuere. A carved figure representing him stands at Papawai.