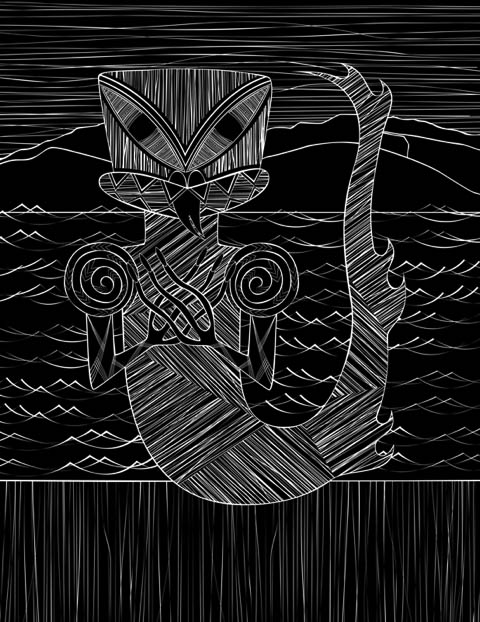

KO te kainga i noho ai tenei taniwha, kei Wai-marama, kei Here-taunga. Ka noho nei, a, ka roa, ka puta te aroha ki tona tuahine, ki a Pari-kawhiti. Ko te kainga o te tuahine kei Wai-rarapa. Kaore a Ngarara-huarau i mohio, kei hea tona tuahine e noho ana, engari katahi ka pihongia ki nga hau. Ka pau nga hau te pihongi, ka tae ki te hau tonga ka rangona e ia te kakara o tona tuahine. Katahi ka haere mai ma te moana, me te pihongi haere tonu mai; tae rawa ki te ngutu-awa o Pahawa, kua tuku atu te kakara o tona tuahine i te hauauru. Ka haere atu a Ngarara-huarau ma roto i te awa o Pahawa. Ano ka tae ki te ngutu-awa o tetehi awa, ka kite ia i te rere; he nui te tiketike. Ka oho tona mauri, e kore ia e eke ki runga. Ka huaina te ingoa o taua awa ko Mauri-oho-o-Ngarara-huarau, i taua ra i karanga-tia ai taua ingoa tae noa mai ki tenei ra.

Heoi, ka rere te taniwha nei, kia eke ia ki runga. Kihai i eke. Ka tu ona waewae ki waenganui o te pari, ka tupeke ake nga waewae o muri, ka tu ki te tūnga o nga peke; katahi ka rere, ka eke ki runga. Ka haere i roto i taua awa eke noa ki te upurangitanga ki roto o tetahi hiwi, ko Maunga-rake te ingoa. Ka eke ia ki runga, ka rongo i te ngenge, ka whakatuapuku i tona tuara. He mea mohio e nga tangata ki te openga o nga peke i te whenua, ka tapaia te ingoa o taua wahi ko Hau-tuapuku-o-Ngarara-huarau.

Ka haere ia, ka tae ki tetahi awa, ko Koura-rau te ingoa, 10 maero pea te matara mai i te wahi i noho ai tona tuahine. Ka noho i roto o Koura-rau. Ko te tikanga o tenei ingoa, he nui no te koura-wai o roto i taua awa. Heoi, ka noho nei te taniwha, ko tana mahi, he patu i nga tira haere; ara, he kai i nga tangata, horopuku tonu, ahakoa he kawenga ta te tangata, ka horomia pukutia e taua taniwha—ahakoa he tamaiti i runga i te hakui e waha ana, ka heke tahi raua ki roto i te kopu o te taniwha nei—ahakoa nga tokotoko me nga taiaha, ka pau katoa te horo.

Ka mahara mai nga iwi o te taha moana, ki nga tira o reira, kei nga kainga o uta e noho ana. Ka pera hoki te mahara o nga iwi o uta nei ki o ratou tira i ahu atu ra ki te taha moana, kei reira e araitia ana e te tupuhi o te moana te tae ki te mahi kai moana hei maunga mai ma ratou ki o ratou kainga i uta nei. Kaore! kua pau i a Ngarara-huarau.

No muri mai ka kitea e etahi tangata, kua noho he taniwha ki roto o Koura-rau. Ka haere te rongo o te matenga o nga tangata o Wairarapa ki te tai-rawhiti, katahi ka mohiotia e nga iwi o reira, kua ahu mai a Ngarara-huarau ki te upoko o te motu nei. Ko tana mahi ano tenei i Wai-marama, he huna i nga tangata o reira. No te haerenga atu nei o Ngarara-huarau i Wai-marama, ka ora nga tangata o reira. Ka mauria atu te rongo e nga tira haere, ka rongo nga tangata o Here-taunga kua mate nga tangata o Wai-rarapa, ka mauria mai hoki te rongo o nga mahi a Ngarara-huarau i Wai-marama, ka rongo nga iwi o Wai-rarapa nei.

Heoi, ka rapua e nga iwi o Wai-rarapa nei he ritenga e mate ai a Ngarara-huarau, a, ka kitea, koia tenei: Me mounu kia puta ki waho i tona rua i noho ai, a, me taki haere kia uru ki roto ki tetahi ngaherehere. Ko taua ngahere me tapahi he umu mo ia rakau, mo ia rakau, ko tetahi taha me waiho kia mau ana. Ko nga rakau e tu ana i te taha o te huanui ma te auta haeretanga a te taniwha e turaki nga rakau, a, ma te hinganga o tetahi rakau ki runga i tetahi rakau ka turaki, a, ka tamia, ka kore e tino kaha; hei reira ka werowero ai ki te tokotoko, ki te huata, me te whiu ki nga patu me nga pou-whenua, a ka mate ia. Heoi nga whakamaramatanga mo te ritenga e mate ai; me nga karakia ki to ratou atua.

Heoi, ka whakaetia e te iwi enei ritenga katoa. Katahi ka whiria he taura. Ka oti, ka tapahia haeretia nga rakau o te taha o te huanui hei haerenga mo Ngarara-huarau. Ka oti, ka patu te kuri; ka mutu ka kowhiria nga toa tokorua, ka whakapatia o raua waewae ki te atua kia tere ai te oma, ka whakaponotia te hau o nga tangata nei me ta raua kuri-mate, me te taura hei tukutuku i te kuri ki te waha o te rua o te taniwha. Ka tae raua ki runga o te rua ka tukutuku i runga i te taura. Kaore ano kia tae ki waenganui o te pari ko te tiaho o nga whatu kua puta ki waho o te rua; no muri i puta ai te upoko. Te putanga mai, ka haere nga tangata nei—te haere a te taniwha te haere a nga tangata. E haere ana nga tangata nei ano ko tiurangi! ara, ko to manu e kiia nei he kāhu. Na te mea ano ka ngaro nga tangata nei i roto i te ngahere ka tomo tahi hoki te taniwha. No te oinga o te hiku ka pa ki te rakau kua oti te tapahi ra, ka hinga ki raro—ko te oinga o te upoko, ka hinga nga rakau, ka auru nga peka ki tetahi rakau, ka hinga, katahi ka hingahinga nga rakau, ka tamia a Ngarara-huarau ki te whenua. Nawai ra i kaha; kua kore e kaha; e werohia ana ki nga tokotoko, e patua ana ki nga pou-whenua, a, ka mate a Ngarara-huarau.

Katahi ka haea te puku. Anana! e whakapapa ana te tangata, te wahine, te tamariki i roto i te puku. Heoi, ka tanumia nga tangata, ka hoatu ma Mahuika e kai a Ngarara-huarau. Ko te upoko ka tapahia ka whakamaroketia, a, whakakohatu tonu iho. Ko te karakia nana i tiki i taki a Ngarara-huarau, ara, ko te tapuae, ko “Pawhakaoho,” ko “Tu-mania,” ko “Tu-paheke.”

Ka mutu nga koreo o tenei taniwha; i kite au i te upoko kohatu me te Mema nei, me Piukenana—kei te taha tonu o tona whare e tu mai nei ano.

The original home of this taniwha was Wai-marama (about twenty miles south of Napier), in the Here-taunga district. He dwelt here for a long time, and then felt a longing to see his sister, Pari-kawhiti, who lived in Wai-rarapa. Ngarara-huarau did not know where his sister lived, but (to find out) he proceeded to sniff the various winds. After trying them all, when he came to the south wind, he experienced the sweet scent from his sister. So he started on his way to find her, coming by the sea, sniffing as he came, till he reached Pa-hawa (Pahaoa, about twenty miles north of Cape Palliser), where the scent of his sister came from the west, so he directed his course up the river. When he arrived at the mouth of a certain stream, he found a waterfall which was very high. His heart was startled, for he thought he would not be able to ascend it. This place is called to this day “The startled heart of Ngarara-huarau.”

But the taniwha made a jump at the fall, but failed to get up it. Then he placed his legs in the middle of the cliff and drew up his hind legs so that they were at the same place as his fore legs; then he sprang up and reached the top. After this he followed up the stream to its source in a certain hill named Maunga-rake. When he got on top he felt very tired, and so he stretched or rounded his back, a fact which men arrived at by seeing places dug out by his fore legs, and hence has this place always been called “Hau-tuapuku-o-Ngarara-haurau.”

After this he went on to a river named Koura-rau, which was about ten miles distant from the place where his sister dwelt, and at Koura-rau he remained. The name of this place is derived from the plenty of koura (fresh water cray-fish) found there. And so the taniwha remained there. His occupation was to kill the travelling parties passing that way—that is, he used to swallow them all, even if they had loads on their backs: mothers carrying children on their backs, men with spears or taiahas, all went down his capacious throat.

The people who dwelt at the sea-side imagined that the travelling parties from there were remaining at the inland settlements. It was the same with the inland people, who thought that their travelling parties who had gone to the coast to bring back fish, &c., were detained by bad weather at the coast. But not so; they had been consumed by Ngarara-huarau.

Some time after some people discovered that a taniwha had taken up his abode at Koura-wai. When the news of the deaths of these people of Wai-rarapa reached Wai-marama, then it was known by the latter people that Ngarara-huarau had come towards the head of the island. His occupation at Wai-marama had been of the same kind—viz., the consuming of man. But when the news reached them of Ngarara-huarau, then they felt safe; and when the news of the deaths at Wai-rarapa reached the people of Here-taunga, then the latter people sent word of Ngarara-huarau’s doings to Wai-rarapa.

So now, then, the people of Wai-rarapa sought means by which they might compass the death of Ngarara-huarau, and after a time decided on measures as follows: To entice him out of his lair by a bait, and lure him along to enter a certain forest. In the forest the trees were to have a umu or scarf cut in each tree, leaving part uncut, so that the writhing of the taniwha should cause them to fall on the others and bring them down on top of him, and thus press on him and prevent him using his strength; then could he be speared, and the weapons be used to slay him. This was the explanation of the proposal, besides invocations to their god.

All these arrangements were consented to by the people. Then was a rope made, and the trees scarfed along the road which Ngarara-huarau was to follow. Then a dog was killed, and two brave fellows selected, their legs being touched with the god to make them swift to run, whilst the hau, or spirit of the men, their dog, and the rope, were subjected to invocations to make them sure. When the men got to a place above the cave, they let down the dog by the rope, and before the bait had reached mid-cliff, the flaming rays of the eyes of the monster were seen coming forth, followed by his head. On his coming forth the men fled, followed by the taniwha; the men fled like the flight of the hawk. When they reached the forest the taniwha entered with them, and as his tail lashed the trees that had been partly cut through, they began to fall; and as his great head moved from side to side, the trees fell on the others, and all came down, pressing Ngarara-huarau to the earth. He struggled and struggled till he was exhausted, and then was he speared, and the clubs did their work, and thus died Ngarara-huarau.

His body was then cut open. Behold! there were layers of men, women, and children inside him! After that the men were buried, and Ngarara-huarau was given to Mahuika (father of fire, i.e., he was burnt). The head was cut off and dried, and it turned into stone. The karakias, or incantations used to draw forth Ngarara-huarau, were those known as the Tapuae, “Pa-whakaoho,” “Tu-mania,” and “Tu-paheke.”

Here ends the story of this celebrated taniwha. I have seen the stone head, and so has Mr. W. C. Buchanan, for it stands near his home.