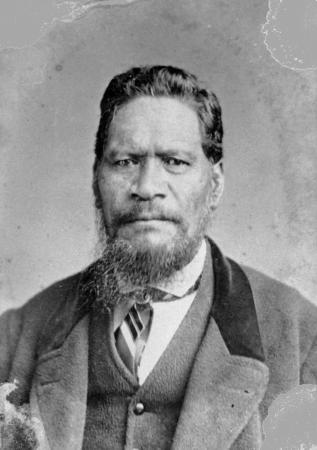

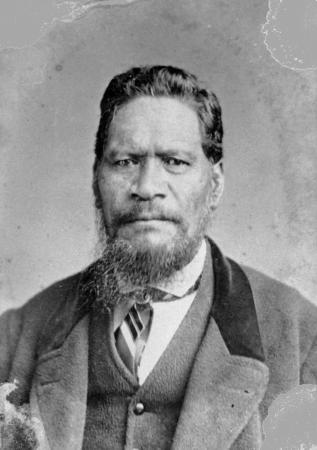

Karaitiana Takamoana, 1870s

Takamoana derived chiefly rank among Ngati Te Whatu-i-apiti and Ngati Kahungunu in Heretaunga (Hawke’s Bay) through his mother, Te Rotohenga, also known as Winipere. Winipere married twice: Takamoana’s father was Tini-ki-runga, of Rangitane and Ngati Kahungunu descent; he belonged to Ngati Rangiwhaka-aewa and Ngati Te Whatu-i-apiti. Takamoana was said to have been born in Wairarapa. Te Meihana Takihi was Takamoana’s brother. Henare Tomoana and Pene Te Uamairangi, whose father was Hira, were his half-brothers.

As a young warrior, in the early 1820s, Takamoana fought at the battle of Te Roto-a-Tara, near Te Aute, against a force of northern tribes led by Mananui Te Heuheu Tukino II of Ngati Tuwharetoa. He was one of the Heretaunga chiefs who refused to flee to the safety of Nukutaurua, on the Mahia peninsula. Consequently, he was captured at Te Pakake pa, inside Te Whanganui-o-Orotu (Napier Harbour), about 1824, when Waikato forces invaded the area. He was carried away to Waikato as a captive, but released through the magnanimity of Te Wherowhero. Takamoana was present when Te Momo-a-Irawaru and Ngati Te Kohera attempted to take possession of the area around Te Roto-a-Tara in about 1824 or 1825; as the war leader of Ngati Te Manawa-kawa, a hapu of Ngati Te Whatu-i-apiti, he was one of those responsible for driving out the invaders. After this victory Takamoana may have joined the Ngati Te Whatu-i-apiti leader Te Pareihe at Nukutaurua. The records do not mention him again until Te Pareihe sent him to arrange a peace with Ngati Te Upokoiri, Ngati Raukawa, and other former enemies of Ngati Te Whatu-i-apiti in the Manawatu area, about 1838.

By the 1840s Takamoana was an influential chief of the younger generation. He was the brother-in-law of Tareha, one of the great leaders of Ngati Kahungunu. He was the leading man of Te Awapuni village when the missionary William Colenso arrived in Heretaunga in December 1844, and was one of five chiefs who signed the deed of transfer of the land which was to become the Waitangi mission station. Takamoana studied in Colenso’s school, learning to read and write. He became a Christian, taking the name Karaitiana (Christian). His relationship with the self-righteous and rigid Colenso deteriorated, however, and in a violent quarrel between Kurupo Te Moananui and Colenso in January 1850 Karaitiana took the part of Te Moananui, although he later intervened on the missionary’s behalf.

In December 1850 Karaitiana welcomed the arrival of Donald McLean, investigating the availability of land for purchase by the Crown. In 1851 Karaitiana was one of the signatories to the sale of the Waipukurau and Ahuriri blocks, in which the Crown acquired 600,000 acres of land in Hawke’s Bay. Like other Maori leaders he looked forward to the establishment of towns and the trade opportunities that they represented.

Land sales soon became a contentious issue in Hawke’s Bay. Karaitiana was closely associated with Kurupo Te Moananui, Tareha and Renata Kawepo in opposing Te Hapuku’s attempt to monopolise the role of Maori agent for sales to the Crown, and his sales of lands to which he and his associates had little claim. Matters came to a head in 1856 over a block north of the Ngaruroro River. Te Hapuku was determined that payment be made for the land. Karaitiana and Te Moananui’s party prepared to make war if necessary to prevent the sale.

Karaitiana’s determination to oppose irregular land sales was strengthened by his attendance at the meeting called by Iwikau Te Heuheu Tukino III at Pukawa in November 1856. In February 1857 he accompanied District Commissioner G. S. Cooper on a tour to point out the possessions of his hapu, Ngati Hawea, within land sold or proposed for sale by Te Hapuku. This was a deliberate challenge to Te Hapuku. In the same month Karaitiana gave warning to Te Hapuku that he must quit his pa at Whakatu, which stood on disputed territory.

War with Te Hapuku finally began in August 1857 over the issue of timber at Te Pakiaka, a stand of bush near Whakatu, claimed by Te Moananui and misappropriated by Te Hapuku’s party. Karaitiana’s role was that of war leader. In three engagements his forces were consistently successful and by March 1858 Te Hapuku had conceded defeat and withdrawn inland to Poukawa. Karaitiana’s mana was in the ascendant. He was regarded as the political heir of Te Moananui, who died in 1861, despite his rejection of the authority of the Maori King, which Te Moananui had supported. However, Karaitiana, Tareha and Renata Kawepo supported the King’s runanga system of Maori self-government. Karaitiana also became an advocate of regional unity; in 1860 he visited Poverty Bay to put forward his idea that Maori of the East Coast, Hawke’s Bay and Wairarapa should consider themselves one tribe, founded by their common ancestor, Kahungunu.

In November 1863 Karaitiana held a meeting at Pawhakairo (near present day Taradale) to decide whether the Heretaunga plain should be let on a long lease. He wanted the Crown to take a 21 year lease, otherwise he would allow individual Pakeha to run stock for short periods. He also planned to organise Maori to run sheep and cattle. Crown agents increasingly recognised Karaitiana as arbiter over the Heretaunga plain. This led to a breach with Tareha, who formed a coalition with Te Hapuku.

For political reasons Te Hapuku and Tareha were inclined to support the Pai Marire missionaries who visited Hawke’s Bay in 1864. A meeting Karaitiana called in April 1865, to force the people of Heretaunga to declare themselves either Hauhau or loyal to the government, proposed an attack on the Hauhau, which government officers considered to be a thinly disguised attack on Tareha. When a band of Pai Marire erected a niu pole in their village on the Ngatarawa plain, over which Karaitiana was in dispute with Te Hapuku, Karaitiana demanded that they cut it down. Government officers restrained him from going in force to do so himself, regarding the true cause of conflict to be land rather than loyalty to the Queen.

However, Karaitiana and his allies continued to prepare for a war against the Hauhau. When Hauhau occupied Omarunui, seven miles from Napier, in September 1866, Karaitiana and Renata Kawepo collected their people and went to Napier. In October an advance was made by troops and militia under Lieutenant Colonel G. S. Whitmore, and a Maori contingent led by Karaitiana and others, and the Hauhau were driven out. For his part in this engagement Karaitiana was later awarded a sword of honour.

In the 1850s and 1860s Karaitiana had been an enthusiastic land-seller. He had become accustomed to a comfortable lifestyle, maintained on credit extended by Pakeha storekeepers. Lessees of the Heretaunga lands under Karaitiana’s control, who wished to ensure that they would have the first refusal on the freehold, encouraged him and other chiefs to make use of credit at their stores. By 1867 he was heavily in debt and by 1869 was facing writs, summonses and warrants on all sides.

His expenditure included the arming and equipping of 80 young men of his tribe to continue operations against the Hauhau and Te Kooti, and the purchase of a trading vessel, the Henry. In 1869 he dispatched 200 followers to the Taupo region to help in the hunt for Te Kooti, for which he was inadequately recompensed. By this time his creditors were pushing him to sell the valuable Heretaunga block. When the block had passed through the Native Land Court late in 1866, Karaitiana, who regarded it as his special property, had wanted the only grantees to be himself and his brother Henare Tomoana. But when he was assured, incorrectly, that other grantees would have no power to sell or deal with the block, he consented to its being registered in the name of 10 grantees. They represented the interests of the 16 to 18 hapu, consisting of several hundred people, who had occupation rights in the block. The other grantees were forced, through the pressure of their debts, to sign a contract to sell, and on 6 December 1869 Karaitiana and Henare Tomoana also signed. Since it was apparent that their debts would swallow all the purchase money, Karaitiana arranged secretly for bonuses of £1,500 for Henare Tomoana and £1,000 for himself, to be paid in 10 annual instalments.

Karaitiana then became unwilling to sell and wanted his share separated from the others, so that his people would not lose their lands on account of his personal debts. He refused to sign the conveyance of the block, and went to Auckland to lay before the government the grievances of Hawke’s Bay Maori regarding their lands, and to ask Donald McLean for a grant to pay his debts and those of his brother Henare Tomoana. As a result of his visit it was arranged that Charles Heaphy, as commissioner of native reserves, should visit Napier to set up some inalienable land trusts. Karaitiana returned to Napier without any tangible benefits, retired to Pakowhai and remained there in a state of sadness and depression. After further threats of writs, Karaitiana signed the conveyance of Heretaunga; Karaitiana and five fellow grantees were entitled to receive only £754 16s. 9d. of their £7,000 share of the purchase money after storekeepers’ accounts had been met. In fact, owing to an error, they were paid £2,387 7s. 3d.

Through his Rangitane associations Karaitiana was involved in negotiations for the sale of the areas known as the Forty Mile Bush and the Seventy Mile Bush, near the Tararua and Ruahine ranges in Southern Hawke’s Bay and Northern Wairarapa. Government agents had made strenuous attempts to buy the areas throughout the 1860s. Karaitiana was willing to sell, but was determined to get full value for the blocks. The government was prepared to pay less than half the amount Karaitiana demanded, but he held out, following T. P. Russell’s advice that the government would eventually pay whatever was asked.

In 1871 Karaitiana succeeded Tareha Te Moananui as member of the House of Representatives for Eastern Maori. (He had stood unsuccessfully against Tareha in 1868.) Maori MHRs were limited in what they could achieve, and Karaitiana referred to the deficiencies of the system in a speech to the House in 1871. Nevertheless, he made known his intention of working to settle land grievances through Parliament. In 1871 and 1872 there appeared the beginnings of what became known as the Hawke’s Bay Repudiation movement, advocating the repudiation of all Crown and private land deals on the grounds of fraud. The movement was led by Henare Matua of Porangahau, and supported by the brothers H. R. and T. P. Russell. At a large meeting at Pakipaki in June 1872 Karaitiana and Henare Tomoana spoke against the movement, and at a subsequent meeting at Pakowhai in July, Karaitiana snubbed Henare Matua. He intended to have the government appoint a commission to investigate land sales in Hawke’s Bay and promised that if this was not done he would join the Repudiation movement.

At the same time Karaitiana was arranging funds to set up schools for his people at Omahu and Pakowhai. Late in 1872 it was announced that a commission to inquire into land alienation was to be set up. The commission sat from February to April 1873, but it was soon clear that, limited in its powers and its capacity to hear scheduled cases, it would not lead to restitution of lost lands. A huge meeting at Pakipaki, attended by Karaitiana and all the other Heretaunga leaders except Tareha, decided to agitate for a new commission with larger powers, and to work for a change of government.

Karaitiana was by now a committed Repudiationist, and in May he contributed £100 to the cause, which was in financial difficulties. From 1873 to 1876 he continued to work for the movement, preparing land cases for the Supreme Court, despite H. R. Russell’s questionable methods and an alliance with Henare Matua which was never whole-hearted: in too many land disputes they were on opposite sides. In 1876 Karaitiana and his brother, Te Meihana Takihi, mortgaged their shares in the Awa-o-te-Atua block to H. R. Russell for £4,000, to enable the Repudiation movement struggle to continue.

In 1876 Karaitiana was returned as MHR for Eastern Maori despite an unsuccessful attempt by the Hawke’s Bay superintendent, J. D. Ormond, to set up Henare Matua as an alternative candidate, in the hope of splitting the Repudiationists’ vote. Karaitiana remained a member of the General Assembly until his death.

Karaitiana is said to have had three wives in the 1870s, and it is possible therefore that he had renounced his Christianity. The names of his wives are not recorded, nor are the names of his children, except for one named Arapeta Te Piriniha. When Karaitiana Takamoana died at Napier on 24 February 1879, he was said to be between 60 and 70 years old. His funeral, attended by a large number of Maori and Pakeha, was conducted by the Reverend Samuel Williams on 1 March. He was buried at Pakowhai, in a brick tomb opposite the site of his house.