Te Aohuruhuru

A gem of delicate ancient-style Maori story telling is the legend of Te Aohuruhuru, of which the Maori version appeared in Sir George Grey’s Nga Mahi a Nga Tupuna. He never translated this story into English, and this has been very sensitively done by the late W. W. Bird, whose version we are presenting here.

A roa rawa tona nohoanga ki tenei koroheke, a muri iho ka tahuri taua koroheke ki te hakirara i a ia.

Ko te tikanga tenei o tana hakiraratanga i a ia. No to raua moenga i te po, roa rawa raua e moe ana, ka maranga taua koroheke ki runga, ka titiro ki tana wahine tamahine, kua warea e te moe. Ko ona pakikau kua pahuhu ke ki raro i te kowhananga a nga ringaringa, a nga waewae, i te ainga a te ahuru. Katahi ka tahuna e ia te ahi, ka ka te ahi, ka tirohia e ia nga pakikau, ka takoto kau ia. Katahi ka mahara te koroheke ra ki te nuinga o tona pai. Kowatawata ana nga uru mawhatu i te hana o te ahi; ko tona tinana, ngangana ana: ko tona kiri, karengo kau ana; ko te kanohi, ano he rangi raumati paruhi kau ana; ko te uma o te kotiro e ka whakaea, ano he hone moana aio i te waru e ukura ana hoki i te toanga o te ra, ka rite ki te kiri o tuawahine.

Taro rawa te tirohanga o taua koroheke ki te pai o tana wahine tamahine, muri iho ka whakaarahia e ia ona hoa koroheke o roto i te whare ki te matakitaki ki te ataahuatanga o tana wahine. I a ratou e matakitaki ana i a ia, katahi ano ia ka oho. Oho rawa ake ia, koia e matakitakina ana e te tini koroheke o roto i te whare ra.

Heoiti ano ka maranga te wahine ki runga, ka mate i te whakama. Heoti ano ko te rangi i pai ra kua tamarutia e te pokeao; ko te uma kakapa ana, ano e ru ana te whenua. Ka tinia ia e te whakama. Katahi ka rarahu nga ringa ki nga pakikau, ki te uhi i a ia. Katahi ka rere ki te kokinga o te whare; ka tangi, tangi tonu a ao noa te ra.

Awatea kau ana, ka haere te koroheke ra ratou ko nga hoa, ka eke ki runga i te waka, ka hoe ki waho ki te moana ki te hi. A i muri o te koroheke ra ratou ko nga hoa kua riro, katahi te wahine nei ka whakaaro ki te he o tana tane ki a ia, katahi ka mahara kia haere ia ki te whakamomori. Na, tera tetahi toka teitei e tu ana i te tahatika, ko te ingoa o tenei toka inaianei ko Te Rerenga o Te Aohuruhuru.

Katahi te tamahine ka tahuri ki te tatai i a ia, na ka heru i a ia, na ka rakei i a ia ki ona kaitaka, ka tia hoki i tona mahunga ki te raukura—ko nga raukura he huia, he kotuku he toroa, ka oti. Katahi ano te tamahine ka whakatika, na ka haere, ka piki, a ka eke ki runga o te toka teitei, ka noho. Katahi ano ka kohuki te whakaaro o te tamahine ki te tito waiata mana.

Ka rite nga kupu o taua waiata; ko te tane ratou ko nga hoa kei te hoe mai ana ki uta. Ka tata mai te waka o te tane ki te taketake o te toka e noho ra te tamahine i runga, ko te koroheke nei kua pawera noa ake te ngakau ki te purotutanga o tana wahine taitamariki. Katahi ratou ka whakarongo ki te wahine ra e waiata ana i tana waiata. Ka rongo ratou ki nga kupu o te waiata a te wahine ra. Ano!

torino kau ana mai i runga i te kare o te wai, ano te ko e pa ana ki tetahi pari, na ka whakahokia mai, ano te mamahutanga ki tona koiwi. Ana! Koia ia, ko te hou o te waiata a tuawahine, mataaho mai ana ki nga taringa. Koia tenei:

‘Naku ra i moe tuwherawhera,

Ka tahuna ki te ahi

Kia tino turama,

A ka kataina a au na.’

Na ka mutu tana waiata, katahi ia ka whakaangi i taua toka nei ki te whakamoti i a ia. Katahi ka kite mai taua koroheke ra i a ia ka rere i te pari. I kitea mai e ia ki nga kakahu ka ma i tona rerenga ai.

Katahi ka whakau mai to ratou waka ki te take o te toka i rere nei te wahine nei, ka u mai, u noa mai ka kite ratou i a ia e takoto ana, kua mongamonga noa atu. Ko te waka whakairo nei kua paea ki te akau, kua pakaru rikiriki. A kua ngahae hoki te waka whakairo a tenei koroheke, ara te pai whakarere rawa atu o te tamahine nei. A mohoa noa nei maharatia tonutia e matou te ingoa o tera toka ko Te-Rerenga-o-Te-Aohuruhuru. A maharatia tonutia hoki e matou nga kupu o tana waiata. No te taenga mai hoki o nga tauhou ki konei, ka arahina ratou e matou ki te toka nei kia kite.

Te Hiko Piata Tama-i-hikoia

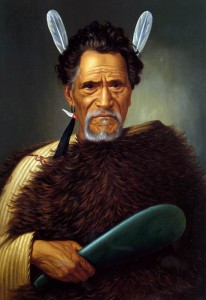

Te Hiko Piata Tama-i-hikoia was one of the leading Wairarapa chiefs from the 1840s to the 1880s. The date and place of his birth are uncertain; it may have been at Te Ngapuke (Te Waitapu, near Tuhitarata) in the 1790s. His principal hapu were Rakaiwhakairi, Ngati Kahukura-awhitia, and Ngati Rangitawhanga; his tribal affiliations were with Ngati Kahungunu, Rangitane, Ngati Ira and Ngai Tahu of Wairarapa. Te Hiko was descended from the ancestor Kahungunu through Rakaitekura and Rangitawhanga, from whom he inherited rights over lands in Southern Wairarapa.

The early adult life of Te Hiko was shaped by the invasions of Wairarapa in the 1820s and 1830s by northern and west coast tribes. The most serious was a war expedition of about 1826, made up of Te Ati Awa, Ngati Tama and Ngati Mutunga, together with some Ngati Toa and Ngati Raukawa. After the Wairarapa people had beaten off an attack at Pehikatea pa (near present day Greytown) about 1833, Pehi Tu-te-pakihi-rangi and Nuku-pewapewa, anticipating a further attack, led most of their people to Nukutaurua on the Mahia peninsula. Te Hiko and his family were among those who took refuge there.

Nuku-pewapewa led an attempt to return to Wairarapa in the mid 1830s. It failed but he did manage to capture Te Uamairangi and Te Kakapi, the wife and the niece of Te Wharepouri of Te Ati Awa. The price for the ransom of Te Kakapi was the return of Wairarapa to its former inhabitants. After this negotiation Te Hiko and his people, with other Wairarapa hapu, returned in a migration which was not completed until about 1842.

By the time of his return Te Hiko was married to Mihi Mete, and had two children approaching adulthood, a son, Wi Tamehana Te Hiko, who was one of the missionary William Colenso’s teachers by the mid 1840s, and a daughter, Ani Te Hiko, later to marry Wi Hutana. Te Hiko was recognised as the leader of Rakaiwhakairi and Ngati Rangitawhanga.

The return of the Wairarapa people coincided with the beginning of Pakeha interest in the region for settlement and for sheepfarming. In the mid 1840s Te Hiko leased land to Angus McMaster, an early runholder. McMaster and his wife, Mary, settled at Tuhitarata after an 11 day journey on foot from Port Nicholson (Wellington). Thus McMaster became Te Hiko’s client, living under the protection of his mana, and known to the Wairarapa people as ‘Hiko’s Pakeha’. The two men were sometimes at odds, when the one thought the other was encroaching on his rights, but their close relationship endured and extended to their families. The descendants of the McMasters often called their children by names associated with Te Hiko. Angus’s son Hugh was also known as Tuhitarata. After the Pakeha family was established, Te Hiko built his pa at Te Waitapu, not far from their homestead. He lived there for the rest of his life.

When the government began buying land in Wairarapa, Te Hiko, like many chiefs who had ‘adopted’ a Pakeha, would not sign any deed of cession unless he had an absolute assurance that McMaster’s interests would be protected. As a result McMaster came to control about 13,000 acres in the Tuhitarata, Matiti, Mapunatea, Otuparoro and Oporoa blocks, much of it leased from Maori owners.

Te Hiko and his people benefited from these arrangements. They made profits from trade in pork, potatoes and wheat with the growing settler population. And though the rents were low for such large areas, they increased year by year, from £300 in 1847 for all Wairarapa leased land to over £800 a year in 1850. Te Hiko and his fellow chiefs found leasing so advantageous that they rejected government efforts to buy land in 1848 for the proposed ‘Canterbury settlement’. As a result, the settlement was located in the South Island.

In the 1850s the government continued its efforts to buy Wairarapa land, and to break the alliance of Pakeha squatter and Maori landowner. Governor George Grey visited the district and gave an assurance that the rights of squatters, like McMaster, to their homesteads and to the essential parts of their runs would be protected. Donald McLean, the chief land purchase commissioner, made the breakthrough in 1853 with the purchase of the Castlepoint block, and from that time on land-selling was under way in Wairarapa.

It was the younger men who were keen to sell and tried to persuade their elders to agree. This caused a good deal of conflict. Raniera Te Iho-o-te-rangi and Te Manihera Te Rangi-taka-i-waho were prominent among the younger men; Te Hiko’s son Wi Tamehana was also involved. In general Te Hiko was opposed to sale, as the published deeds show. In the first series of sales his name appears only on the deed affecting McMaster’s Tuhitarata lands, and up to 1876 his name appears on only four deeds of sale; his son’s name is on eight, Raniera Te Iho’s on thirteen, and Te Manihera’s on twenty-six. Te Hiko held aloof from the sale of the Turakirae block, which was effected in Wellington by Hemi Te Miha, Ngairo Takataka-putea and Raniera Te Iho. In an effort to change Te Hiko’s mind, McLean offered reserves for all people affected, and payments to be spent on hospitals, schools and a flour mill.

It is ironic that Te Hiko, previously opposed to land sales, should be remembered chiefly for the sale of his fishing rights in Lake Wairarapa to the government. It is clear that he had important rights over the lake. While they were not exclusive, decisions about the lake had to include him. In particular, he was the guardian of its fishing resources. Maori and Pakeha interests were in conflict over the lake. The government was eager to control the outlet, to keep the bar open and so reduce the flooding of fertile lands. Maori opposed this, because one of their major resources, the eel harvest, was at its best when the lake was in flood.

Te Hiko sold his rights in 1876; the price was £800 to him and 16 others, and an annual pension of £50 for him. His previous salary of £50 as an assessor under the Native Circuit Courts Act 1858 had been withdrawn because of his opposition to some land sales. ‘Hiko’s Sale’, as it was afterwards called, stirred up so much opposition that other leading chiefs petitioned Parliament. This resulted in the 1891 commission of inquiry into the ‘Claims of natives to Wairarapa Lakes and adjacent lands’.

Although Te Hiko has been accused of betraying his trust, the story of the sale suggests that he, by now a very old man, was placed under extreme pressure by those who wanted to sell. Te Manihera started to apply pressure in 1874. He suggested that he and Komene Piharau should represent one group of the lake’s owners; Te Hiko suggested that he and Hemi Te Miha should represent the others. In 1876 they all went to Wellington. Although Te Hiko seemed ready to co-operate in the sale, his real purpose was to settle problems that had arisen over the sale of the Pukio block. He told Edward Maunsell, the government negotiator, that he would not discuss the lake while Pukio was not settled. He also warned Hemi Te Miha, on the way to Wellington, not to consent to the sale of the lake. But when all the parties met, Te Miha was the first to agree to the sale and append his signature. After this Te Hiko felt that he had no option but to give his consent.

There was a further quarrel about the method of payment. Te Manihera wanted it paid in Wellington at once; Te Hiko wanted it paid over in Wairarapa so that the people could be present and benefit from the sale. As a result Te Manihera and Komene Piharau refused to sign. As Hemi Te Miha was of lesser rank, the sale of the fishing rights to the government became ‘Hiko’s Sale’.

In 1891 before the commission of inquiry Piripi Te Maari-o-te-rangi connected Te Hiko’s consent with his resentment of the pretensions of Raniera Te Iho. As early as 1872 the government agent, Richard Barton, had been authorised to treat with Maori owners for control of the opening of the lake. He had excluded Te Hiko, and dealt only with Raniera Te Iho and Piripi Te Maari. Te Hiko was already incensed by Te Iho’s appropriation of a reserve out of the Turakirae block. Raniera Te Iho was a young man, not yet qualified to take a leading part and he was ignoring the mana of his elder. Te Hiko’s consent to the sale of the fishing rights may well have been influenced by a belief that in any case those rights were being taken away by the acquisitive younger leaders.

Hostility about payment continued. Over Te Manihera’s violent objections, Maunsell paid over the money at Featherston. On Te Hiko’s instructions half was paid to Wi Kingi Tu-te-pakihi-rangi, the successor to the chief who had negotiated the return of Wairarapa from Te Wharepouri. Wi Hutana, Te Hiko’s son-in-law, used the other half to erect a sawmill at Pukio, which was intended to benefit the people at large.

At the time of these negotiations Te Hiko was old and infirm. He died on 1 July 1881, aged about 90 years. His wife had died in 1873, aged 75 years. They were both buried at Tuhitarata, in the cemetery where members of the McMaster family were buried. In 1905 his daughter Ani presented his canoe, Te Herenga Rangatira, which he had always used on the Ruamahanga River, to the Colonial Museum. T. H. Heberley carved it in the manner of a war canoe, and it is now displayed at the Canterbury Museum.

Te Ika a Maui

“Te tuara ko Ruahine, nga kanohi ko Whanganui a Tara, tetahi kanohi ko Wairarapa, te kauae runga ke Te Kawakawa, tetahi kauae ko Turakirae”.

“The back is the Ruahine ranges, with regard to the eyes, the salt water one is Wellington Harbour the other eye – the fresh water one – is Lake Wairarapa, the upper jaw is Cape Palliser and the lower jaw is Turakirae Head”

(Source: Riley 1990: 78-4)

Maui Tiki a Taranga, Maui the coiled hair of Taranga (Taranga being his mother) the mischievous demi-god, caught Te Ika a Maui, the fish of Maui which is now known as the North Island of New Zealand. The fish was the shape of a giant stingray whose tail is in Muriwhenua (North Cape) with the wings extending to the eastern and western extremities of the island. In the Wairarapa the places associated with Te Ika A Maui are:

- Wairarapa Moana – Lake Wairarapa – This is known as ‘Te Whatu o Te Ika a Maui’ or ‘the eye of the fish of Maui’. This is the freshwater eye, the other eye is Wellington Harbour or Te Whanganui a Tara which is the saltwater eye.

- Kawakawa – Palliser Bay is known as ‘Te Waha o Te Ika a Maui’ or ‘the mouth of the fish of Maui’.

- Turakirae Head and Matakitaki a Kupe (Cape Palliser) are known as ‘the jaws of the fish’

- The combined Rimutaka, Tararua and Ruahine ranges that pass up the middle of the North Island are referred to as ‘the spine of the fish’

- The Tararua Mountain Range lake called Hapuakorari is known as ‘the pulse of the fish’.

Te Ikapurua

Te Ikapurua pa

Te Korou, Te Retimana

Te Korou and his family were among those who about 1834 were forced to flee from Wairarapa to Nukutaurua on the Mahia peninsula by the invasion of northern tribes. Te Korou was captured by Te Ati Awa, but he escaped near Orongorongo after tricking one of his captors, Te Wera of Ngati Mutunga. When no one else was near, Te Korou offered to rearrange Te Wera’s load, seized his long-handled tomahawk, gashed Te Wera’s hands which he had put up to protect himself, killed him, and escaped into the bush. When peace was arranged between the Wairarapa people and the invaders Te Korou was among the negotiators. Ngati Kahungunu, Rangitane and other tribes returned from the north from 1841 on, and Te Korou, already past middle age, re-established his position as one of the principal leaders in Northern Wairarapa. His interests and influence extended from present day Masterton to Eketahuna, and from the Tararua range eastwards to the coast.

In the 1840s Te Korou and his family were drawn towards Christianity. By the time he had been forced to go north, he had three children: a daughter, Erihapeti (Elizabeth); a son, Te Tua-o-te-rangi (or Te Turuki, later known by his baptismal name, Karaitiana or Christian); and a third, probably another son. When the missionary William Colenso visited Te Korou at Kaikokirikiri, near present day Masterton, he found Erihapeti about to be married to Ihaia Whakamairu. Since 1845 the whole community at Kaikokirikiri had been under the influence of a Christian teacher, Campbell Hawea, and in 1848 Colenso was happy to baptise all four Te Korou generations: Te Korou himself, who took the name Te Retimana (Richmond); his aged mother Te Kai who took the name Roihi (Lois); his wife Hine-whaka-aewa, who became Hoana (Joan/Joanna); his daughter, Erihapeti, and her husband, Ihaia Whakamairu; his four sons (two of them still boys); and two grandsons. Colenso noted that Karaitiana was a ‘fine youth’ and a fluent reader of the Bible in Maori.

Colenso recorded that Te Korou was determined to preserve his lands for his children, and to prevent his family from being demoralised by contact with Pakeha. But he was unable to live up to this hope. Already, in 1844, he had tried to lease land in the Whareama valley to the runholders Charles Clifford, Frederick Weld and William Vavasour, and had been annoyed when they decided to seek drier pasturage further north. In 1848 Te Korou was among those who discussed with Francis Dillon Bell, the New Zealand Company agent, the possible sale of Wairarapa land for the proposed ‘Canterbury settlement’, later sited in the South Island. Te Korou took part in other transactions; his willingness to do so probably arose from the fact that others were leasing lands in which he had an interest, without consulting him. There was argument in Kaikokirikiri over the leasing of the Manaia block to W. B. Rhodes and W. H. Donald. Later Te Korou proved to be one of the most co-operative in land negotiations with Henry Tacy Kemp.

As Pakeha settlement penetrated Wairarapa, tensions grew between younger men wishing to sell land, and their leading elders, who at first preferred to lease. However, to preserve something for themselves from the maelstrom of land-selling the older chiefs, whose mana would earlier have gone unchallenged, became sellers themselves. It is likely that on the one hand Te Korou, and on the other his son Karaitiana and his son-in-law Ihaia Whakamairu, were caught up in this kind of rivalry.

The pressure which Te Korou had to face came from the Small Farm Association, a body seeking to settle farmers on small land-holdings. The association sent Joseph Masters (after whom Masterton was to be named) and H. H. Jackson to Kaikokirikiri, at Governor George Grey’s suggestion. Their arguments were persuasive; Ihaia Whakamairu returned with them to Wellington to complete the sale. There is no record that Te Korou objected to the sale, but the sellers included some of the younger members of his family. In the various transactions which transferred the site of Masterton to the Crown, the names of Karaitiana, Erihapeti and Ihaia Whakamairu are prominent. Te Korou was directly involved in a number of sales, mainly to the south and east of Masterton, in the Maungaraki, Wainuioru and Whareama districts. He also signed the Castlepoint deed. Both he and Karaitiana sold parts of the same blocks together, but for the most part they did business separately.

From the 1860s on Karaitiana appears to have taken over from his father; at the 1860 Kohimarama conference he represented Kaikokirikiri. From the beginning of Native Land Court sittings in the Wairarapa in 1866 Karaitiana and Erihapeti represented the interests of the family. Te Korou did not appear often; in 1868 he was described as ‘an old man of Ngati Wheke’. Both father and son are described in government documents as supporters of the King movement in 1862. But they, with other Wairarapa leaders, were adherents more because of dissatisfaction over land sales and payments than because of any special attachment to the King.

Te Retimana Te Korou was said to be over 100 when he died at Manaia in early January 1882. Ihaia Whakamairu invited all his European friends to join in the mourning. Several leading settlers joined in a procession of 300 people to the Masterton cemetery.

Te Maari-o-te-rangi, Piripi

Piripi Te Maari-o-te-rangi was prominent as a defender of the rights of the Wairarapa people to their lands and lakes, from the 1860s to his death in 1895. The evidence which he and his brother, Hohepa Aporo, gave to the Native Land Court stated that his father was Aporo Waewae. But he was sometimes reputed to have been the son of Te Maari-o-te-rangi, whose brother Te Kai-a-te-kokopu had, until the 1840s, supreme rights over hapu using the food resources of Onoke, the southern Wairarapa lake.

There is no doubt about other relatives. Piripi Te Maari’s mother was Hariata Ngarueiterangi of Ngati Hinewaka; his elder brother, Piripi Iharaira Aporo, of the Whareama district; his younger brother, Hohepa Aporo, who married Maikara Paranihia. His sisters were Ihipera Aporo, who married Hemi Te Miha (with whom Piripi was closely associated); and Ani Aporo, who married Ratima Ropiha of Porangahau. His hapu were Ngati Tukoko, Rakaiwhakairi, Ngati Rakairangi, Ngati Manuhiri, Ngati Hinewaka (a branch of Ngai Tu-mapuhi-a-rangi), and Ngati Hineraumoa.

Some time after 1832 Wairarapa was again invaded by tribes from the north and west, and Wi Tako Ngatata, a leader of Te Ati Awa, killed Te Maari-o-te-rangi. The Wairarapa tribes then began their withdrawal to the north for safety. Many went to Nukutaurua on the Mahia peninsula. Some stayed at Waimarama in Central Hawke’s Bay, among them the family of Piripi Te Maari. There Piripi was born, perhaps in 1837; and he was taken back there for burial after his death.

In the early 1840s members of Piripi Te Maari’s family began to return to Wairarapa. He joined them in the early 1850s, by which time he was married to Meri Te Haeata. While he was away, he had been educated at the school of CMS missionary William Williams at Waerenga-a-hika, near Gisborne. This education equipped him for his future activities as the ‘man of affairs’ for his people.

His reputation was enhanced by his success as a farmer. He leased land from his relatives and ran sheep and cattle. He operated on such a large scale that he needed to employ Pakeha workers. The skill he showed in adopting the agricultural and business practices of the settlers helped him to achieve recognition as a man competent to deal with land and fishing rights. He was consistently concerned that Maori landowners should lose none of their rights. This concern led him into the great battle of his life, the struggle to prevent settler encroachment on the rights and lands of the owners of the two Wairarapa lakes. The lands bordering on the lakes had been purchased for the government by chief land purchase commissioner, Donald McLean, in 1853. The deeds of sale were not clear about the precise boundaries of the blocks purchased by McLean, but he had given a verbal agreement that the lakes themselves should stay in Maori hands, together with the low-lying swampy areas, below the high-water flood line. He had agreed, too, that any settler who opened the shingle bar dividing the lower lake from the sea would be fined £50.

The two lakes were very important as a source of food. In southerly storms the shingle bar at the seaward end of the lower lake would build up to form a dam; brackish water would spread inland, and the eels in the lake would be brought towards the sea and could be caught in huge numbers against the bar. In good years 20 tons of eels could be taken and dried. Dried eels were exchanged with other tribes for preserved birds and seafood; this exchange system extended as far as Wairoa and Gisborne. Dried eels were also important as gifts.

By the 1860s Pakeha pastoralists were enviously eyeing the flood plain of fine silt building up on the borders of the lake, and in some cases using it without permission. But the floods which brought the harvest of eels hampered the Pakeha farmers. By the end of the 1860s they were seeking the power to open the shingle bar without the agreement of the owners of the lakes. In 1868 Piripi Te Maari, with Raniera Te Iho-o-te-rangi and others, asked the government to honour the arrangements made with McLean. For a time things went amicably. Sums of £40 were paid for permission to open the bar, but Piripi and others did not give permission during the height of the eel season, between January and March.

But this did not satisfy the settlers, who put pressure on the government to purchase the lakes, and so bring to an end the annual flooding of their properties. In 1872 a meeting of Rakaiwhakairi was called at Te Waitapu, near Tuhitarata, in response to approaches made by a local settler, Richard Barton. The meeting decided against selling the lakes, a position maintained by Piripi for the rest of his life. However, in 1876 a deal was concluded, known as ‘Hiko’s Sale’: Te Hiko, Hemi Te Miha and 15 others were induced by Te Manihera Te Rangi-taka-i-waho and Edward Maunsell (the government agent) to sign away their fishing rights to the lower lake. When Maunsell came to pay the purchase money, he was met by Piripi Te Maari who objected to the sale because only a fraction of the owners of the lakes had been consulted.

By this time Piripi Te Maari was a prominent leader. He was chairman of a committee opposed to any further sale of Wairarapa lands, a committee probably of the runanga of Wairarapa, founded in 1859. By the 1880s he was regarded as the leader in all matters to do with the lakes. He was a member of the committee of 12 appointed at Papawai in 1883 to investigate all grievances between Maori and Pakeha in Wairarapa. He made numerous appearances in the Native Land Court on his own behalf and on behalf of others, often as a trustee for minors. He also became an elder in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, being baptised in that church at Te Waitapu on 2 June 1887, and helping to translate the Book of Mormon into Maori. His religion brought him into conflict with Ngati Porou, who sought the assistance of Te Kotahitanga to exclude the Mormons from the country.

Through the 1880s the battle over the lakes continued. Piripi Te Maari applied to the Native Land Court in 1881 to hear the claims of the non-sellers of Lake Wairarapa. At the first hearing, in 1882, he sought to get the government’s case dismissed, on the grounds that it was based on the purchase of only 17 persons’ interests. This tactic was successful. A second hearing, in 1883, registered Piripi Te Maari, Raniera Te Iho and 137 others as owners of the two lakes. This was a significant victory.

Maunsell returned to the attack in 1885. At Tauanui in lower Wairarapa he met Piripi Te Maari who agreed to put the matter before his committee, but warned that no one with a real interest in the lakes was willing to sell. Maunsell replied that the government was determined to acquire the lakes and would buy individual shares. During these discussions Piripi set out the grievances of the owners. First, an earthquake in 1855 had raised up land which had been below the original high-water mark; this land belonged to the Maori owners, but the government had sold some of it. Second, the lakes were gradually filling up, and this was destroying the fishing. If the government decided to open a permanent drain to the sea the fishing would be totally gone. Third, commercial hunters were shooting the duck population. All this was happening on lakes which still belonged solely to Maori owners.

By 1886 Piripi Te Maari was ready to come to a compromise. At a meeting at Papawai attended by the native minister, John Bryce, the owners of the lakes agreed to let the bar be opened at the end of April. Later that year Piripi offered to give up two months of the fishing season – April and May. This was a major concession. With Wi Hutana, he met the new native minister, John Ballance, on 12 November 1886, representing the committee of owners.

But the prospects of an agreed solution were shattered by the Ruamahanga River Board. The board declared Lake Wairarapa to be a public drain, and asked the government to support it in its effort to open the lakes. (The property of its chairman, Peter Hume, was most affected by flooding.) In 1888 the board, to test the right it claimed, sent 33 men, accompanied by 2 constables, to work with spades to open the bar. Piripi Te Maari arrived with his followers, and after a tense discussion, put his protest into a statement which was signed as ‘received’ by the board’s representative.

Piripi Te Maari then petitioned the government to inquire into the situation. The 1891 commission of inquiry into the Wairarapa claims was chaired by Alexander Mackay. It returned an ambiguous report. It stated that the flood line was the boundary of Crown purchases at least in the Turanganui block, that Maori ownership of the lakes included the shingle spit, and that endangering the fishing rights of the owners was contrary to the Treaty of Waitangi. But it added that the lake owners were not justified in allowing land sold by them to be flooded.

In 1892 the Ruamahanga River Board tried to force a channel. Its men were resisted by 100 Maori and their solicitors. A police inspector watched and advised each group in turn. But the owners were threatened with prosecution for obstruction, and let the board’s workers do their job.

Piripi Te Maari did not give up. He took a case to the Court of Appeal, only to have it dismissed. He organised a further petition, and gave notice that he intended to seek a ruling from the Privy Council. Another petition, in 1895, to the Native Affairs Committee of the House of Representatives, secured a favourable decision, that the owners of the lakes had been wronged and should be compensated.

This was the only victory Piripi Te Maari lived to witness. On 26 August 1895 he died at Greytown and was buried at Waimarama; he was survived by five of his eight children from two wives, Meri Te Haeata and Heni Te Taka. Next year Tamahau Mahupuku arranged a settlement by which the lake owners received compensation in the form of £2,000 and the promise of ‘ample reserves’. But it was not until 1915 that 230 Wairarapa people were given 30,486 acres in the Pouakani block at Mangakino, in Waikato. The land was of poor quality and part was sold later, but some Wairarapa families settled these distant lands and several are there still.

Te Matorohanga, Moihi

Moihi Te Matorohanga, also known as Moihi (or Mohi) Torohanga, was of the major Wairarapa hapu Ngati Moe. His family hapu was Ngati Whakawhena. He was also kin to Ngai Tahu of Wairarapa, Ngai Tukoko, Ngati Kahukura-awhitia and Ngati Kaumoana. His various hapu were the intermarried descendants of Kahungunu, Tara, Rangitane and Tahu. His father was Tiina; his mother, Whenuarewa. It is likely that he was born in the late eighteenth or early nineteenth century, as he was an old man when he died, a while before August 1876. The place of his birth was probably a settlement in Wairarapa called Te Ewe-o-Tiina. He does not appear to have married, and left no children.

As a child Te Matorohanga was trained at two whare wananga: Te Poho-o-Hinepae in Wairarapa, and Nga Mahanga at Te Toka-a-Hinemoko in the Nga Herehere area of Te Reinga, north of Wairoa. His teacher at Nga Mahanga was Nuku. He may also have studied at a whare wananga near present-day Napier.

About 1836 he spent a period of four months at Uawa (Tolaga Bay) in Te Rawheoro, the whare wananga of Te Aitanga-a-Hauiti. During this time Nopera Te Rangiuia, the main tohunga, accused Te Matorohanga of witchcraft and of causing the death of Te Rangiuia’s son. Te Matorohanga denied the accusation and never returned to Te Rawheoro.

After this, Te Matorohanga became the authority on genealogies at Te Poho-o-Hinepae whare wananga, and lived for some time at Te Whiti pa, near Gladstone in Wairarapa. With his close relatives, Eraiti Te Here and Te Mapu, he owned land near Greytown, comprising part of Te Ahikouka block, from Te Umu-o-Puata to Te Rata. He built a house there.

In 1865 at Te Hautawa, Papawai, a group of people who were clearing bush asked Te Matorohanga to tell them the stories of the elders to pass on to their children. Te Matorohanga agreed, but said that a house should be found and set apart for the purpose. The house of Terei Te Kohirangi and Pene Te Matohi on the bank of the Mangarara Stream (Papawai Stream) was offered and accepted. The group of listeners included Hoani Te Whatahoro Jury, who, in 1863 at Ngaumutawa in Wairarapa, had begun to write down Ngati Kahungunu traditions and genealogies as dictated by the tohunga Nepia Pohuhu. He now performed the same service for Te Matorohanga.

Te Matorohanga warned his listeners ‘it will take years to write down all that I am about to tell you’. Indeed, the recorded information is exceedingly wide-ranging and detailed. It includes stories of creation, accounts of the discovery and settlement of Aotearoa, genealogies of ancestors, and incidents from tribal histories. Te Matorohanga’s version of the story of Kupe has been retold many times.

During the sessions at Te Hautawa, Te Matorohanga sometimes seemed to regret his decision, because of the tapu nature of the traditions. In May 1865 he became angry with Te Whatahoro, telling him that he did not fully realise the depth of the matters they were examining, which went to the roots of Maori cosmogony. He again emphasised that the teaching must take place in a special house, not in quarters associated with daily living.

On one occasion Te Matorohanga demonstrated to his listeners his powers as a prophet. On 10 May he told the people that his night had been disturbed by dreams of a red sky. It was a sign that some disaster would befall Ngati Moe. He sent his pupil, Riwai, to Huru-nui-o-rangi, where Pirika Po confirmed Te Matorohanga’s prophecy by warning that Ngati Te Waiehu were coming to make trouble. Riwai returned to Te Hautawa on 11 May bringing with him a group of Ngati Moe kinsmen for protection. Te Matorohanga said he had fallen asleep waiting for Riwai and had seen the harbinger of death, Tu-nui-o-te-ika, coming to ambush him. Riwai then told Te Matorohanga of the warning he had received from Pirika Po; Te Matorohanga assured him that the danger had been averted.

When the sessions ended on 26 May, Te Matorohanga told his listeners that whether copied into books or not, the teaching was still tapu. Disregarding their protests he carried out a tapu-removing ceremony. Before dawn he heated stones in the small fire that had been burning in the house, raked the embers, and cooked 12 very small potatoes. When they were ready he put the books to lie among them, and recited a karakia.

Te Matorohanga shared his knowledge with other interested people. He trained numerous students, but always referred them to Nepia Pohuhu and Rihari Tohii if he was uncertain about any issue. Pohuhu in his turn told his students that if he made a mistake, Te Matorohanga would correct it.

It is not known exactly when or where Te Matorohanga died. Elsdon Best later gave an account of the death of a tohunga who may have been Te Matorohanga. The tohunga was eating with relatives when he had a sign which he interpreted as his approaching death. He went aside to pray, then asked his people to put up a tent for him where he could go to die. His main pupil came and was asked to perform the ritual whakaha, inhaling the tohunga’s breath of life in order to pass on his mana. The old man then waited; as the sun sank below the hills, it laid a pathway on the sea for his spirit to follow to join his ancestors.

Te Whatahoro retained his transcripts of Te Matorohanga’s teachings until, in February 1899, at Papawai, Tamahau Mahupuku called attention to the words of James Carroll, that the tales of the ancestors should be collected while there were elders still alive who could explain them. He suggested setting up groups to encourage this. At a meeting held at Tamaki-nui-a-Rua, Hawke’s Bay, on 15 March 1907, much previously transcribed material was read aloud before the sub-committee known as the Komiti o Tupai of the Tane-nui-a-rangi committee. The accounts given by Moihi Te Matorohanga and Nepia Pohuhu and transcribed by Te Whatahoro were among those unanimously considered to be accurate. The approved teachings were written down and endorsed with the stamp of the committee.

In 1910 the Tane-nui-a-rangi books of the teachings of Moihi Te Matorohanga and Nepia Pohuhu were sent to the Dominion Museum in Wellington to be published. They were not published, but were eventually copied by Elsdon Best. Te Whatahoro’s original complete manuscript of the teachings of Te Matorohanga is no longer extant, although fragments may remain, and there is a copy of one section made by Te Whatahoro in 1876 when the original manuscript was falling apart.

The surviving transcripts have been of considerable interest to twentieth century scholars. S. Percy Smith published in 1913 and 1915 a two-volume work called The lore of the whare-wananga. He claimed to have used ‘original documents which [Te Whatahoro] lent me’ as the basis for the work. These documents may have included transcripts of some of the original talks given by Te Matorohanga and Nepia Pohuhu. However, Smith used other less reliable sources, so that not all aspects of his work reflect authentic Ngati Kahungunu tradition. Elsdon Best drew on his copies of the Tane-nui-a-rangi books in the preparation of The Maori, Maori religion and mythology and his other works. It is clear now that Smith, Best and subsequent writers on Maori religion and tribal tradition are indebted to Te Matorohanga and his peers, and to their scribe, Te Whatahoro.

Te Potangaroa, Paora

Paora Te Potangaroa was the son of Ngaehe, of Ngati Kerei and Ngati Te Whatu-i-apiti, and Wiremu Te Potangaroa, a leader in the Mataikona area of Wairarapa, of Te Ika-a-Papauma, a hapu of Ngati Kahungunu. Through his father’s mother, Nau, Paora was related to the Hamua people, a section of Rangitane.

In 1853 Paora signed the deed of sale of the Castlepoint block, a huge area stretching from the Whareama River inland to the Puketoi range, and north to the Mataikona River. It was the first major purchase made by the chief land purchase commissioner, Donald McLean, in Wairarapa. Paora later signed away the Tautane block, in the Porangahau area, and the Waihora block, but of all the Wairarapa chiefs he was to be the most resistant to the lure of land-selling.

Paora’s position as a prophet and leader in Wairarapa was recognised from the early 1860s; he was asked to accept nomination as Maori King but refused. In 1878 he inspired the many hapu of the upper Wairarapa valley to build a large carved house at Te Kaitekateka, later called Te Ore Ore, near Masterton. This area was under the mana of Wi Waaka, a staunch supporter of the runanga movement and the King movement, and a protector of the emissaries of Pai Marire. During construction animosity developed between Paora and Te Kere, a master carver and prophet from Wanganui. Te Kere and Wi Waaka began to resent Paora’s growing influence, which tended to undermine their positions. Te Kere was particularly incensed at the size of the planned house, 96 by 30 feet. Having prophesied that it would take eight years to finish the house, he departed to build a rival house for Ngati Rangiwhaka-aewa at Tahoraiti.

In spite of Te Kere’s prediction, the house was finished by 1881. Paora bestowed on it, in derision of Te Kere’s powers as a prophet, the name Nga Tau e Waru (The Eight Years). The house incorporated many unusual features. The carvers Tamati Aorere of Ngati Kahungunu and Taepa of Te Arawa made use of unique double ‘S’ patterns, swastika-like motifs, and unusual rafter and panel paintings. Inside the house Paora had erected a stone believed to be a medium of communication with the world of gods and spirits. In addition, at Paora’s behest, Te Kere had carved into the ridgepole above the door, in a position where it could not easily be seen, a representation of male and female genitalia in the act of coitus. The intention was to remove the tapu of chiefs entering the door beneath it. When Wi Waaka entered the house he collapsed, semi-paralysed, and had to be helped outside. With hindsight, this collapse was attributed to the effect of the carving, designed to protect the tapu of Paora himself.

When the house was being carved Paora was at the height of his influence and popularity. He was preaching Christianity expressed in Maori concepts and when he appeared in public, people gathered round him for instruction; between these appearances he spent much time in meditation. Associated with the completion of Nga Tau e Waru were a number of his prophecies which predicted that a new and great power was to come to the people from the direction of the rising sun. Various interpretations were made: it was believed to herald the arrival of the gospel of Jesus Christ, as interpreted by the Mormons; and it was believed that missionaries would come from the east and set in place a new church. In 1928, when the religious leader T. W. Ratana visited Te Ore Ore at the request of the people, he removed the stone set up by Paora inside Nga Tau e Waru, repositioning it outside. The move silenced the medium. The coming of the Ratana faith is now widely believed to be the fulfilment of Paora’s prophecy.

In 1881 Paora announced that he had experienced a prophetic dream; he called his people together to interpret his vision. His mana was so great that the crowd at Te Ore Ore in March 1881 was variously estimated at between 1,000 and 3,000. Huge preparations had been made for their arrival, including the preparation of a great feast – a pyramid of food 150 feet long, 10 feet wide and 4 feet high. Many Pakeha visitors attended the gathering, some out of curiosity and scepticism. On 16 March 1881 the gathering awaited Paora’s prophetic utterance. About 1 p.m. he emerged from Wi Waaka’s house and presented his revelation in the form of a flag divided into sections, each bordered in black. Within each section were stars and other mystical symbols. It was raised to half-mast on the flagpole in front of the meeting house. Paora unsuccessfully asked his people to interpret its message. In spite of the scepticism and anger of those anxious for an immediate miracle, he refused to explain his meaning. The next day he appeared again and told the crowd: ‘Look at the flag. Tell me what it means.’ He made no further explanations. The gathering ended in disorder and heavy drinking.

Several weeks later Paora emerged from seclusion to make a declaration to his followers: in future they should neither sell nor lease land, should incur no further debts and refuse to honour debts already incurred. The meaning of at least part of his flag now became apparent. The black-bordered sections of the flag represented the huge blocks of land already alienated. The stars and other symbols represented the inadequate and scattered reserves, the sole remainder of a once great patrimony. Paora had been moved to prophecy by the failure of his people to understand the process by which they were dispossessing themselves.

Three months later Paora Te Potangaroa died. Pakeha authorities greeted his death with relief; they had feared the ‘fanaticism’ his movement had caused. The tangi was held at Te Ore Ore and the body carried by hearse to the settlement at Mataikona. As Paora lay dying, he had presented his son Kingi with a box of silver, the money taken at the Te Ore Ore gathering in fines for drinking. This treasure paid for his funeral.

Te Raekaumoana

Te Raekaumoana lived in the 1600s and was such an important person that the hapü of the Maungaraki Ranges still retain him as their eponymous ancestor, Ngāti Raekaumoana. He was known as both a chief and a tohunga, a person who possessed great spiritual powers and could perform magical feats. He had as his main dwelling a pa called Okahu that had been built near the opening of the Kourarau Stream by the Ruamahanga River. Te Raekaumoana is mentioned here because it was through his heroic deeds that many places in the north Wairarapa were named by him.

During Te Raekaumoana’s lifetime the people who were to become known as Ngāti Kahungunu had established themselves in many places throughout the southern and central Wairarapa. The descendants of Rangitaane and Kahungunu were living beside each other without trouble but then an unknown assailant killed a Ngāti Kahungunu man called Te Aoturuki. The chief Rakairangi, who was to become the ancestor of the Rakairangi hapū, heard that the people of Te Raekaumoana were behind this deed and so set about to gain revenge on his fallen whanaunga. The taua (war party) of Rakairangi moved up the Wairarapa Valley disposing of several pa and numerous people along the way.

The taua eventually arrived at Okahu Pa and besieged it before breaking through the defences. They thought they would find Te Raekaumoana inside but instead found lesser chiefs who they killed along with many of the other inhabitants. Raekaumoana had received a vision of the impending doom and warned his people that it would be better to see another day rather then fight a futile battle. The younger chiefs remarked “we would prefer to drink from our own streams, rather than ones we do not know”, indicating that they would stay and fight. Raekaumoana left knowing that all that stayed were sealing their own fate.

After killing most of the people of Okahu, Rakairangi ordered that the pa be burnt before they moved on satisfied that they had now gained vengeance. Actually they hadn’t because Raekaumoana and his people had wrongfully been blamed. Anyway Rakairangi did find this out and soon found the real culprits and dealt to them a dose of brutal justice. But anyhow as the pa was engulfed by flame Raekaumoana sat atop of a hill in the distance watching the destruction. The place he was at was called Parinui-a-kuaka near Gladstone; the ridge he was on was to become Uhimanuka (shade made from Manuka) on account of the shade he made for his eyes from Manuka branches.

As he sat watching he grieved for his people and determined that he would gain his own revenge for this callous deed. But first he would have to move far away to gain strength. He then called upon his guardian the eagle called Rongomai. Answering his call Rongomai swept down to his companion where upon the chief climbed upon the giant bird’s back. Now they ascended into the skies where Raekaumoana pointed north. Although a powerful creature Rongomai was not used to carrying the extra weight of a grown man and so needed to rest. Rongomai wriggled and so this place was named Te Keunga o te Atua o Raekaumoana (the wriggling of the spiritual power of Raekaumoana). He then needed to land, where his feet touched the ground became known as Nga Tahora o te Atua o Raekaumoana (the clearings of the spiritual power of Raekaumoana), this was near Masterton. Once ready, they set off again but near the mouth of the Mangapakihi Stream on the Kopuaranga River Rongomai required another rest. This place was called Nga Tahora o te Atua o Raekaumoana (the place where the spiritual power of Raekaumoana lay on the ground). After one more stop they arrived at Pahiatua (the resting-place of the spiritual power). While Raekaumoana carried on north Rongomai went to the cave that we know as Te Ana o Rongomai which he made his home (see Konini).

Raekaumoana sought the people of Hāmua at Tamaki Nui a Rua near Dannevirke. He knew that his safety was ensured as his daughter Hinerangi had married Tamahau, son of the main chief of the area Rangiwhakaewa. The marriage of Tamahau and Hinerangi had sealed the dual lines of descent for proceeding generations. The couple had by this time already moved to the Wairarapa but the people of Rangiwhakaewa recognised Raekaumoana. After describing the events that had displaced himself and his people, the people of Tamaki Nui a Rua raised a taua. This group travelled back to the Wairarapa enlisting allies along their path. A further series of battles were fought with Rakairangi’s people. The result being that Raekaumoana came out on top in this instance meaning that an equilibrium was re-established amongst the people of Rangitaane and Ngāti Kahungunu.

It is important to note that during the taking of Okahu, Rakairangi had spared the life of one Turangatahi by placing his own cloak upon the shoulders of the older man. Turangatahi was grateful for this act of kindness, as were his remaining people. While he was taken as a prisoner he was eventually exchanged for land. The victories of Raekaumoana and his allies later on meant that they received lands from Rakairangi, which created a balance in terms of exchange and mana.

Te Rangi-taka-i-waho, Te Manihera

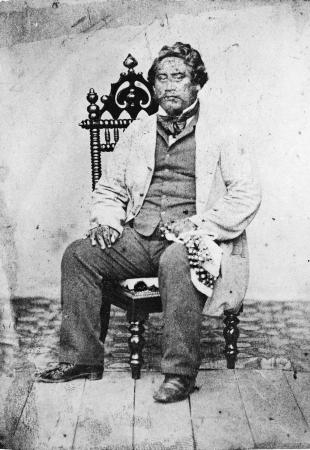

Te Manihera Te Rangi-taka-i-waho

Te Manihera attended William Williams’s mission school at Waerenga-a-hika, near present day Gisborne. While on the East Coast he married Rerewai-i-te-rangi from Tokomaru Bay. In 1841 Pehi Tu-te-pakihi-rangi brought him home to Wairarapa. At this time Pakeha settlers were taking an interest in the sheepfarming potential of the Wairarapa district. Te Manihera’s life was to be greatly influenced by the spread of settlement and pastoral farming.

In the 1840s he was still a young man who had not yet achieved a position of standing. Yet, like many of the younger men in the region, he soon took a leading role in land dealings, in competition both with older leaders and with his own generation. Pakeha regarded him as their staunch friend in the 1840s and 1850s. He eagerly accepted the challenge of the new commercial opportunities created by settlement, and wished to be seen as the equal of older leaders, such as Ngatuere Tawhao, and the new Pakeha gentleman settlers. As early as 1853 he built a large European house; he ran his estates as an individual proprietor, and was noted for his elegant European clothes.

Exploring parties of New Zealand Company settlers and officials visited Wairarapa in 1842 and 1843. In 1844 Te Manihera and two other Maori visited Wellington, staying there with Charles Clifford and William Vavasour. A party of would-be settlers, including these two and Henry Petre and Charles Bidwill, set out with Te Manihera for Palliser Bay and travelled up the Ruamahanga River to Wharekaka and Kopungarara. Te Manihera managed the negotiations for the Maori owners. Two extensive runs were leased at an annual rental of £12 each. Soon Te Manihera and others shifted to Otaraia to be close to their Pakeha.

This was the first of many negotiations in which Te Manihera was involved. Many of them led to quarrels with other leaders whose rights he ignored. He leased land to the settler Archibald Gillies at Tauwharenikau (Tauherenikau) in 1848. His own relatives were so incensed that they talked of killing him, and he was forced to flee for a period into the Tararua Range.

Although by 1853 Te Manihera and other chiefs were earning substantial sums from the leasing of their lands, from that year they consented to the sale of large blocks. Governor George Grey had met the chief objection to sale by guaranteeing that the existing Pakeha lessees could have the first refusal of their homesteads. The district land commissioner, William Searancke, believed that Maori feared that the government would remove them from their lands if they did not sell. In 1852 their missionary adviser, William Colenso, who had always told Maori never to sell, had been removed in disgrace by church authorities, and his influence may have been missed. Over the next 20 years Te Manihera’s name appeared more often than that of any other seller on deeds of sale and receipts.

Much of the proceeds from these sales was frittered away; like many others Te Manihera was lured into debt by traders, and forced to sell more land in order to keep afloat. In spite of his troubles he remained supportive of Pakeha. He was made an assessor in the Native Land Court and in 1853 was host to a public meeting of lower Wairarapa electors in his house at Otaraia. He was himself an elector, through owning land by Crown grant.

In 1854 Te Manihera was the first to sign the deed selling the Kuhangawariwari block from which land was reserved for the Maori township of Papawai. When the town was laid out he apportioned the land; Bishop G. A. Selwyn was granted 400 acres for a Maori college. There were delays (in 1854 there was an outbreak of measles) but by 1855 the government had carried out its promise to erect a flour mill at Papawai. The Reverend William Ronaldson added his support for a township so that he would have a worthwhile congregation. Ngatuere Tawhao, Wi Kingi Tu-te-pakihi-rangi and Te Manihera each led separate groups of their people to settle at Papawai in the late 1850s. But the first two withdrew, after Ngatuere and Te Manihera had quarrelled about control of the mill, and the place became known as Manihera Town. A college, founded in 1860, was not a success and in the late 1860s Papawai had few inhabitants.

Although, in the later 1850s and in the 1860s, some settlers and officials considered Te Manihera to be implicated in both the King movement and Pai Marire, he does not appear to have been a strong supporter of either. He had fallen out with Searancke, and helped destroy the land commissioner’s reputation among Wairarapa Maori by testifying that Searancke had called him a liar. Thus Searancke’s claim that Te Manihera was the leader of the King movement in Wairarapa should be treated with caution. Ronaldson believed that if Te Manihera inclined to the King movement, it was out of dislike for Searancke. In 1859 he supported the government at the King movement meeting at Te Waihenga; and the following year accepted the government’s invitation to go to the Kohimarama conference, possibly to spite Ngatuere. Despite scares among the settlers throughout the 1860s, Wairarapa remained peaceful. Te Manihera’s influence and lack of real commitment to both the King and the Pai Marire movements contributed to this.

Te Manihera was still involved in disputed land deals through the 1860s and 1870s. For example, in 1862 he sold Te Puata (or Taheke) block to the government. On the margin of Lake Wairarapa, this land had been raised above the lake level by the 1855 earthquake; it remained a cause of dispute for years after his death. Then, in 1876, he played a major part in the highly controversial sale to the government of fishing rights in Lake Wairarapa. He induced Te Hiko to go to Wellington on another pretext and there pressured him into consenting to the sale. Te Manihera and Te Hiko fell out over the matter of payment; Te Manihera withdrew from the transaction, with the result that the older man was burdened with the responsibility for it. It became known as ‘Hiko’s Sale’. Te Manihera was one of the most frequent witnesses before the Native Land Court. One of his greatest battles in the court was to persuade it to allow a road to be built through Te Ore Ore block to the coast. He succeeded, but only at the price of earning the enmity of Te Ore Ore people.

In his last years Te Manihera’s vision of Papawai as the political centre of Wairarapa developed its full potential under the leadership of the successor he appointed, Tamahau Mahupuku. To him Te Manihera delegated power to deal with all matters relating to the people, while Hoani Te Whatahoro Jury was to assist with land matters and negotiations with the government. In his old age Te Manihera achieved the status to which he had aspired all his adult life. The controversies were overlooked; he was recognised as a major leader.

For about 12 years before his death on 6 June 1885 Te Manihera had been in ill health, and in low spirits over the death of most of his children. Of the 14 children of his first marriage only 3 survived. All 8 children of his second marriage died before he did. They were all buried at Papawai. He blamed himself for these deaths, believing that he must have violated a tapu. His first wife, Rerewai-i-te-rangi, had died at Gisborne; his second wife survived him.

Great numbers attended Te Manihera’s tangi at Papawai: telegrams announcing his death had been sent to John Ballance, the native minister, to Sir George Grey, to Henare Tomoana, MHR, to Renata Kawepo of Napier, to Henare Matua of Porangahau, and to many of the old settlers in the Wairarapa.