Section of Hiona marae

Section of Hiona marae

Rangitāne people have lived continuously in the Wairarapa region for 28 generations or some 7-800 years.

Beginning with founding ancestors Kupe and Whatonga, they and their descendants have built up a rich history that is found in oral accounts, written records and of course in the names across the landscape.

Within these pages are origin stories of Rangitāne o Wairarapa. There is also information on where and how early Rangitāne people lived.

Rangitāne people have lived continuously in the Wairarapa region for 28 generations or some 7-800 years.

This book profiles a selection of significant Rangitāne tupuna, some of whom lived hundreds of years ago and others who were alive during the early 20th century.

Like all people, those featured had multiple lines of descent. This book focuses on these tupuna’ Rangitāne whakapapa, where they had land interests based on that whakapapa and some of their achievements.

Rangitāne people have lived continuously in the Wairarapa region for 28 generations or some 7-800 years.

Ngāti Hāmua is the paramount hapū of the Rangitāne o Wairarapa iwi.

Inside this booklet you will discover who Hāmua, the eponymous ancestor of the hapū was and where his descendents have established themselves through to

modern times. Quotes from 19th century Ngāti Hāmua rangātira, identifying the tupuna from who they and their 2012 descendents derive their land rights are used throughout.

Rangitāne people have lived continuously in the Wairarapa region for 28 generations or some 7-800 years.

Captain of the ancestral Kurahaupo waka – Whatonga discovered and named the great forest Te Tapere Nui o Whatonga 26 generations ago. His descendents the people of Tara-ika (Ngai Tara) and Rangitāne (Rangitāne) have maintained their relationship with the land from the earliest times through to the present.

This book covers aspects of the history of Te Tapere Nui o Whatonga particularly the area between Opaki/Kopuaranga (north of Masterton) and Pahiatua.

This education resource provides the reader with information about the pre 1950 history of the Ngäti Hämua hapü of the Rangitäne o Wairarapa iwi. It follows on from the Ngati Hamua Environmental Education Sheets that were published in 2005.

There are 6 sheets in total with the first providing an overview of the Ngati Hamua hapu and the ancestors from whom the hapu descends. The following four focus on Ngati Hamua associations with different parts of what we now know as the Wairarapa. The sheets start in the Tararua area in the north, move into Te Kauru or the Upper Valley, keep going south to the lower valley and then move out to coastal areas.

But we seem to forget about them or at least undervalue them.

We think that insects and spiders need more WOWs and heaps less “Ooh yucks”.

Te aitanga a pepeke includes all small creatures including insects, spiders, centipedes, frogs, lizards and others. In Māori mythology Whiro sent an army of small creatures to kill Tane as he climbed up to the heavens to get three sacred baskets of knowledge. Tane used the wind to keep the small creatures away. After getting the baskets Tane made his way back down so Whiro sent thousands of beetles to stop him but Tane beat them too. After this Tane took all the insects and other small animals back to his home in the forest.

Te aitanga a pepeke are important because they

• Keep the balance of nature by keeping pest animals and plants in check

• Pollinate fruits, flowers and vegetables.

• Are primary and secondary decomposers which means they clean up and break down waste from animals, plants and other materials.

• Stop the food web from breaking down.

Besides there are more insects in the world than any other animal. In New Zealand there are estimated to be 20,000 insect and 2,000 spider species. Ninety percent of these are found nowhere else.

Description of a few more interesting trees and plants

Our atua (environments and energy sources) are all around us. Rā the sun, marama the moon, Papatūānuku the earth mother, Ranginui the sky father, Tangaroa the waterways and many more.

Atua have been around for a long time, far longer than any of us. They are our kaitiaki or guardians. We could even say they are like loving grandparents who care for us.

When the atua work together we get fresh water to drink and swim in, food to eat, hot summer days, trees that help us breath, plants to make clothes, trees for building and so many other useful things that we could spend all day talking about them.

The better we get to know the atua the more we learn about how they look after us and the more we think about how what we humans do can affect the atua in good or bad ways.

So whether you are big or small we encourage you to get outside to get to know the atua around your home. You don’t need anyone to tell you what to do or how to do it but just in case you would like some ideas that is what this resource is about.

Just go out and use your senses and after a while you will remember what you are experiencing.

We have pulled together

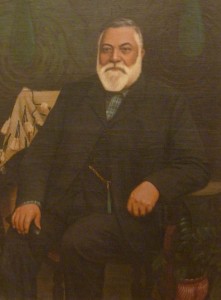

a range of information and ideas to help youJoseph Potangaroa

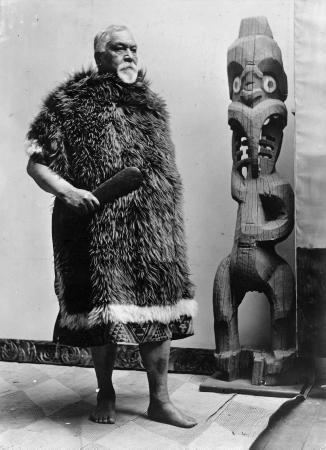

Hoani Te Whatahoro Jury

Hoani’s parents built their first home on land which Te Aitu claimed as her own. The land, called Waka-a-paua, was on the Ruamahanga River, some three miles north-east of Martinborough. There, and in the district north-east of Lake Wairarapa, Hoani spent his early years with his mother’s people, Ngati Moe, a hapu of Rangitane and Ngati Kahungunu. He learnt of the traditional fishing places on the shores of Lake Wairarapa, and Te Aitu showed Hoani, or Tiaki as he was known as a boy, all the boundaries and the special places of their ancestral land. Later he worked as a stockman for Angus McMaster at Tuhitarata, Lake Wairarapa.

Hoani, with his sister Annie and brother Charles, was initially taught to read and write by his father, who later sent him to Wellington to be tutored by a Mr Crawford (Kerewhata). Te Aitu did not agree to her son living with a man whom she did not know. After a month one of his mother’s relatives fetched Hoani back. His further education was at mission schools and, according to family tradition, was paid for by Governor George Grey.

Hoani, with his sister Annie and brother Charles, was initially taught to read and write by his father, who later sent him to Wellington to be tutored by a Mr Crawford (Kerewhata). Te Aitu did not agree to her son living with a man whom she did not know. After a month one of his mother’s relatives fetched Hoani back. His further education was at mission schools and, according to family tradition, was paid for by Governor George Grey.

In 1854, when Hoani Te Whatahoro was 13, his mother died. He and his father then quarrelled over some horses and they went their separate ways. His father, some time later, moved to Glendower, a block of land at Ponatahi, south of Carterton. He took with him the two younger children, eight-year-old Annie and four-year-old Charles. In October 1868, in the Native Land Court at Greytown, Hoani, supported by his father, successfully established his own right, and that of his brother and sister, to Te Aitu’s land. The court awarded Jury’s Island, an area of 55 acres, to Charles and Annie Eliza Jury, and Wharehanga, a peninsula of about 400 acres to the south, to Hoani Te Whatahoro Jury.

Hoani Te Whatahoro became a prolific writer on Maori traditions and customs. He usually acted as a scribe or recorder. He began this work in the late 1850s, when a large gathering of Wairarapa Maori came together to discuss land and political questions. It was suggested that the tohunga present should explain some of the tribal traditions to the assembled people. Three tohunga consented to teach: Te Matorohanga (also known as Moihi Torohanga) was appointed to lecture, and the other two (both unnamed) were to assist by recalling any matters that Te Matorohanga might omit. The Wairarapa people also decided that these lectures should be written down by Hoani Te Whatahoro and Aporo Te Kumeroa. At Papawai, near Greytown, in 1865, Hoani recorded traditions given by Te Matorohanga, with Paratene Te Okawhare and Nepia Pohuhu assisting. He continued to record information from the teachings of Nepia Pohuhu and Te Matorohanga until their deaths in the 1880s.

From about 1870 to 1877 Hoani Te Whatahoro seems to have lived at Putiki, Wanganui, where he was at various times a recorder and an interpreter. In 1868 he was acting as an advocate in the Native Land Court. His duties took him to Horowhenua, Wellington, Wairarapa, Hastings, Gisborne and Tolaga Bay, as well as other parts of the North Island. From 1878 to the mid 1880s he was in Gisborne and the Tolaga Bay area. He moved to Wanganui about 1902 and later farmed at Ohotu, south of Taihape, until about 1909. While living at Wanganui, he continued his interest in tribal traditions and copied Ngati Tuwharetoa manuscripts and information from Te Umukura and Whaiti-nga-rere-waka. For over 40 years he also returned often to Papawai for short periods.

In 1883 missionaries of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints began work among the Maori at Te Ore Ore, near Masterton. Several people, including Hoani Te Whatahoro, were attracted to this faith. From 1886 to 1888 he was one of those who assisted Mormon elders in translating the Book of Mormon into Maori. On 26 June 1900 he was baptised into the Mormon church and at the same time confirmed, at the Papawai branch of the church.

In the 1890s Hoani Te Whatahoro was involved with Te Kotahitanga. This movement advocated self-government for the Maori people through a Parliament, and claimed this as a right based on the Treaty of Waitangi. The Maori parliament wanted Native Land Court work to stop, all Maori assessors to resign and the sale of Maori land to be placed under Maori control. In June 1892 Hoani was elected chairman of the parliament held at Waipatu, near Hastings.

Hoani Te Whatahoro was also a member of the Tane-nui-a-rangi committee, to which the most learned men of Ngati Kahungunu belonged. In February 1899, at Papawai, Tamahau Mahupuku made a plea for the recording of Maori learning from elders with great knowledge. He suggested setting up groups to encourage this, and an appeal was made for old manuscript books. The Tane-nui-a-rangi committee met from 1905 to 1910 to consider the books which they had gathered. Once a manuscript was approved by the committee each page was stamped with the committee’s seal. Some were given to the Dominion Museum where they were copied, but the original manuscripts have vanished.

In February 1907 Hoani Te Whatahoro was elected a corresponding member of the Polynesian Society; he retained this membership until his death. In 1907 ‘An ancient Maori poem’ by Tuhoto-ariki was published in the Journal of the Polynesian Society with a translation by George H. Davies and extensive notes by Hoani Te Whatahoro. In 1909 Hoani Te Whatahoro had published in the society’s journal an article ‘Ko te tikanga o tenei kupu, o Ariki’.

Although Hoani Te Whatahoro made important collections of Maori traditions and nineteenth century literature, much of this material was passed on to several European scholars. Elsdon Best, T. W. Downes, S. Percy Smith and John White all wrote articles which incorporated information supplied by Hoani Te Whatahoro, but made little or no acknowledgement. One of the more important of these articles is Downes’s ‘History of the Ngati Kahu-ngunu’, published in sections in the Journal of the Polynesian Society between 1914 and 1916. Percy Smith, president of the Polynesian Society, used other writings of Hoani Te Whatahoro. He translated and published, under the title The lore of the whare-wananga, the teachings of Te Matorohanga and Nepia Pohuhu that had been written down by Hoani 48 years earlier. The first part of these teachings was printed as volume three of the Polynesian Society’s Memoirs in 1913, the second part was first printed as chapters in the Journal in 1913 and 1914, and then reprinted in 1915 as volume four of the Memoirs. In these publications the ideas, opinions and interpretations of Smith dominate the English translation. Important manuscripts of Hoani Te Whatahoro are now held by the University of Auckland, the Alexander Turnbull Library and the National Museum.

Hoani Te Whatahoro Jury had seven wives and fifteen children. His first wife was Pane Ihaka Te Moe Whatarau, with whom he had Te Aitu-o-te-rangi Wikitoria (also known as Sue Materoa) and Muretu William; his second wife was Hera Ihaka Te Moe Whatarau (a sister of his first wife), with whom he had Meri Kiriwera, Te Waikuini and Te Hiwa. Huhana Apiata was Hoani’s third wife, with whom he had Tiweka Rangihikitia. His fourth wife was Keriana Te Potae-aute, and they had nine children: Tepora, Te Uranga, Puhinga-i-te-rangi Margaret, Renata Te Manga, Takotoroa, Makaretu, Te Rina, Manapouri Te Rina Huitau and Hamuera Porourangi. His fifth wife was Mata Pohoua (also called Mata Te Rautahi); his sixth, Hera Erena Rongo; and his last, Hera Ferris; they had no issue by him, although they did bring up some of his grandchildren.

Hoani Te Whatahoro Jury died on 26 September 1923, at the Greytown home of his eldest daughter, Te Aitu-o-te-rangi. He is buried in the Papawai cemetery. A man of great knowledge, he is said to have completed six of the seven grades of the whare wananga. He is represented in the painted panels of the porch of the meeting house, Hikurangi, at Papawai.

Turakirae is the western headland of Palliser Bay, just east of Wellington Harbour. The saying arose from the legend of a beautiful daughter of a local chief, Miriana. She was courted and wooed in vain by many young chiefs from far and wide.

Meanwhile a slave who had been captured in battle was assigned to serve her, He frequently

followed on her errands into the forest and to the beach. As time passed she grew increasingly

attached to him. This relationship remained in secret for some time but eventually was discovered

by old women of the tribe.

When her father heard about it he was furious and ordered the slave killed in front of her.

The slave, unwilling to submit himself to such an end threw himself off Turakirae. In time

Miriana gave birth to twin sons. While her standing was not to be changed, the boys were to be

accorded the same sttus as their father. At last overburdened by the sorrow of her lovers death

and the daily spectacle of her mistreated sons, she gathered them up and followed their

fathers route over the same cliff.

Nowadays when the cliff is clear it is taken as a sign that Miriana is happy with her sons

in the spirit world. When it is misted over, however, it is taken as a warning that she is

angry and people will die.